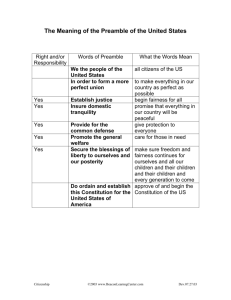

to CENT Paper 2(b): Justice and Fairness

advertisement