Program in DOC

advertisement

Configural Processing 2006: Program

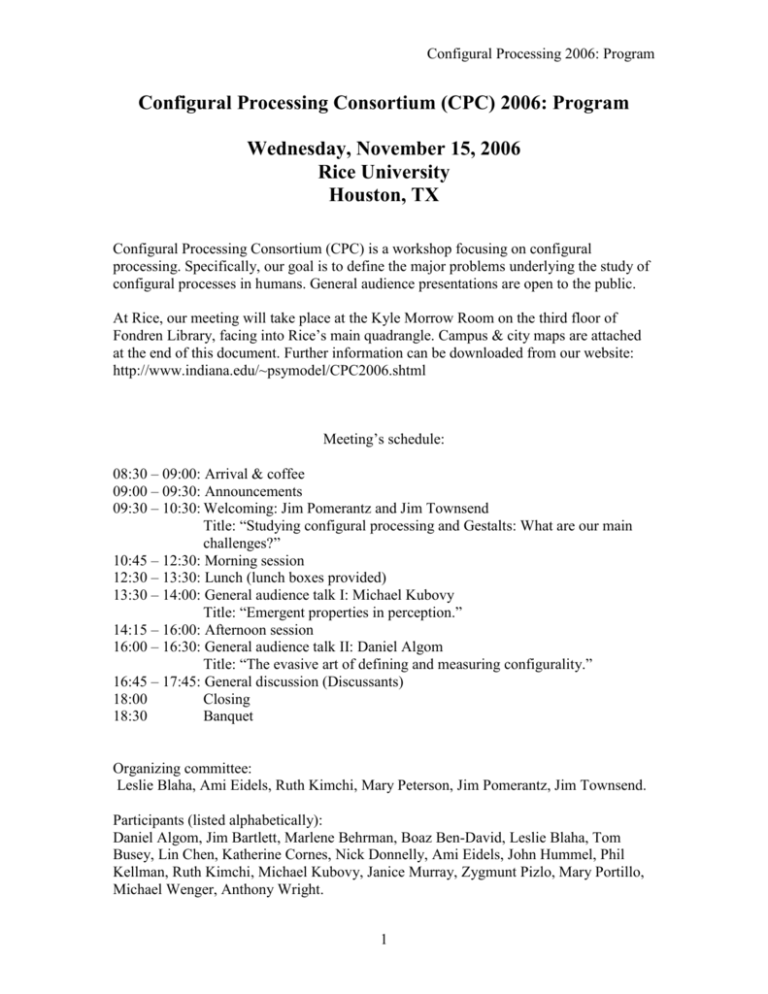

Configural Processing Consortium (CPC) 2006: Program

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Rice University

Houston, TX

Configural Processing Consortium (CPC) is a workshop focusing on configural

processing. Specifically, our goal is to define the major problems underlying the study of

configural processes in humans. General audience presentations are open to the public.

At Rice, our meeting will take place at the Kyle Morrow Room on the third floor of

Fondren Library, facing into Rice’s main quadrangle. Campus & city maps are attached

at the end of this document. Further information can be downloaded from our website:

http://www.indiana.edu/~psymodel/CPC2006.shtml

Meeting’s schedule:

08:30 – 09:00: Arrival & coffee

09:00 – 09:30: Announcements

09:30 – 10:30: Welcoming: Jim Pomerantz and Jim Townsend

Title: “Studying configural processing and Gestalts: What are our main

challenges?”

10:45 – 12:30: Morning session

12:30 – 13:30: Lunch (lunch boxes provided)

13:30 – 14:00: General audience talk I: Michael Kubovy

Title: “Emergent properties in perception.”

14:15 – 16:00: Afternoon session

16:00 – 16:30: General audience talk II: Daniel Algom

Title: “The evasive art of defining and measuring configurality.”

16:45 – 17:45: General discussion (Discussants)

18:00

Closing

18:30

Banquet

Organizing committee:

Leslie Blaha, Ami Eidels, Ruth Kimchi, Mary Peterson, Jim Pomerantz, Jim Townsend.

Participants (listed alphabetically):

Daniel Algom, Jim Bartlett, Marlene Behrman, Boaz Ben-David, Leslie Blaha, Tom

Busey, Lin Chen, Katherine Cornes, Nick Donnelly, Ami Eidels, John Hummel, Phil

Kellman, Ruth Kimchi, Michael Kubovy, Janice Murray, Zygmunt Pizlo, Mary Portillo,

Michael Wenger, Anthony Wright.

1

Configural Processing 2006: Program

Welcoming:

Studying configural processing and Gestalts: What are our main challenges?

James R. Pomerantz, Rice University

Gestalt Psychology will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2012, just six years away.

What has the field accomplished to date, and what challenges remain? Our

accomplishments lie primarily in the successful demonstration of a multitude of powerful

configural phenomena and in establishing the importance and centrality of the Gestalt

question in theories of perception. Our challenges include laying down and adhering to

clear and consistent definitions for the core concepts underlying our research, building

consensus on measuring techniques, and developing formal theories for configural

effects. I will aim in this talk to expand upon and explain this analysis and to offer

suggestions for future progress.

James T. Townsend, Indiana University

Following up on Jim Pomerantz’ excellent points, it seems very likely that most, if not all

attendees to our inaugural CPC conference, would agree that a satisfactory theory of

configural perception is an admirable, if not necessary goal. There are perhaps two major

avenues for approaching theory: 1. Inductive: That is, abstracting and generalizing

empirical regularities having to do with good figures. 2. Starting with a priori ideas of

what the precepts of configural perception ‘ought’ to be. Perhaps Darwin’s theory of

evolution comes close to (1) whereas certain aspects of Einsteins special theory of

relativity (and to some extent, the general theory) bears important aspects of (2).

Theories of configural perception and cognition seem to be growing as a function of both

precepts. I will mention a few major themes in configural cognition that a general theory

should encompass. Some of them are included in my lab’s approach, others not. What

will it take?

2

Configural Processing 2006: Program

General audience talk I:

Emergent properties in perception

Michael Kubovy, University of Virginia

Gestalt phenomena---such as grouping and other forms of perceptual organization---and

configural processing---such as the perception of faces---are examples of emergent

properties (EPs). They are called EPs because one cannot predict the properties of the

complex object (a face, a melody) from the properties of the elements (the list <eyeshape, nose-shape, …>, or the list of musical notes and their associated durations). The

classic example is our inability to predict the state of matter of water at room temperature

(liquid) from the state of matter of its constituents (hydrogen and oxygen) at room

temperature (gas). Some treat emergence as if it were just a relation between properties

of elements and properties of what they constitute when they combine. This

conceptualization is observer-neutral; it makes claims about nature; it is ontological. I

will review the history of the notion of emergent property, and propose that claims of

emergence are not purely ontological; they must be stated with respect to a epistemic

framework. In other words one cannot assert that something is an emergent property in a

context in which the relation between elements and a whole is fully understood. So

within the framework of physical chemistry, the relation between H, O, and H_{2}O is

not an instance of emergence. I apply these ideas to perception, and conclude with a

classification of emergent phenomena, based on two distinctions: (1) cognitive vs.

perceptual emergence; (2) eliminative vs. preservative emergence.

General audience talk II:

The evasive art of defining and measuring configurality

Daniel Algom, Tel-Aviv University

How does something like beauty emerge? Why do some stimuli like faces or certain

emblems form compelling visual Gestalts, whereas others leave the casual observer

unaffected? Why do a brother and sister look alike? These impressions of beauty, holism,

and similarity are as immediate and compelling as are subsequent attempts at justifying

them look forced and unsatisfying. Is there a way to quantify the processing of these

stimuli, thereby distinguishing them from other non-configural stimuli? The answer

remains tentative, as attempts at deriving objective measures of configurailty have been

notoriously unsuccessful. There has long been an informal, intuitive linkage between

configurality and singularly efficient processing produced through interaction among the

various stimulus features. Another influential idea stressed the strong perceptual glue

binding together parts of configural stimuli, compromising full selective attention to

3

Configural Processing 2006: Program

parts. However, available measures of efficiency and/or capacity failed to support the

notion of supercapacity, or even dependency in processing configural stimuli. In a similar

vein, routine measures of selective attention fail to distinguish configural from nonconfigural stimuli. A possible solution to the conundrum implicates the tasks used. They

require decomposition of the stimulus or attention to a single dimension, thereby

relinquishing possible effects of stimulus holism. Tasks that preserve the stimulus as a

whole do reveal configural superiority.

Workshop presentations:

Unit formation revealed by non-linear interactions in the visual nervous system

Marlene Behrmann, Carnegie Mellon University

The Gestaltists believed that perceptual organization arose from global interactions

within the visual nervous system. Whether this is the case has always been controversial

and the emphasis placed on the physiological underpinnings of perceptual organization

has largely waned. In this talk, I examine evidence revealing how a ‘whole’ comes to be

‘greater than the sum of its parts’ at both a psychological and neural level. The data

support the claim that holistic representations reflect non-linear part-part interactions and

that these representations emerge as a function of experience with the whole. Single unit

recording in inferotemporal cortex in two monkeys performing an object discrimination

task reveals increased neural selectivity for learned versus unlearned parts. Furthermore

and of greater relevance, the findings indicate that the emergent unification of the object

is supported by enhanced firing to the specific combination of the learned parts. This

process of unification and the increase in neural selectivity for learned part-part

combinations might account for the ability of experts to discriminate among objects in

their domain of expertise based on configural or holistic representations.

Configural Learning

Leslie M. Blaha, Indiana University

Arguments and evidence abound that configural processing involves either a perceptual

representation or a cognitive processing strategy that is different from the processing of

visual objects in general. Some research argues, for example, for configurality through

holistic representations involving undifferentiated percepts (e.g. Farah, et al., 1998);

others propose that configural processing arises from highly developed or expert

processing mechanisms (e.g. Gauthier, et al., 1998; Townsend & Wenger, 2001). What is

often neglected in these arguments is an explanation for how these “special”

4

Configural Processing 2006: Program

representations or mechanisms developed to the point of configurality. So we are left

with a fundamental question: What are the processes and/or mechanisms by which we

develop either a configural perceptual representation or a configural processing strategy

(or both)? I explore various perceptual learning processes and expert-training paradigms

that represent potential candidates for the configural learning mechanisms. Such learning

appears to manifest itself in both behavioral and neurological measures, but do the

varying measures and methodologies converge on a single configural learning process?

What do EEG/ERP early perceptual components tell us about configurality?

Tom Busey & Bethany Schneider, Indiana University

In this talk we summarize the effects seen in early perceptual components such as the

P100 and N170 that have been attributed to configural or holistic processing. Our goal is

to both look for converging evidence with behavioral findings as well as to provide

some boundary conditions on what manipulations provide configural effects. We also

discuss alternative explanations for these differences that would not require configural

processing.

Tracking the development of face processing

Nick Donnelly, Katherine Cornes, Nouchine Hadjikhani and Julie Hadwin

Centre for Visual Cognition

School of Psychology

University of Southampton.

1

Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging

Massachusetts General Hospital

Harvard Medical School.

The development of face processing across childhood and adolescence has typically been

conceived of as a transition from feature-based, orientation-invariant processing to

configural-feature, orientation-dependant processing. Although broadly correct, there are

significant problems with this view. First, there is a gap between experimental

phenomena and theoretical frameworks for configural processing creating uncertainty

over what develops across childhood and adolescence. Second, evidence of increasing

orientation dependence is drawn from studies comparing only the special cases of upright

and inverted faces. We illustrate the importance of these issues for development with

reference to detection of the Thatcher illusion.

5

Configural Processing 2006: Program

Defining Configural Processing by Elimination

Ami Eidels, Indiana University

Configural Superiority Effect (CSE) marks the faster responses on trials where certain

figures (‘configural’) are presented, compared with responses to other (‘non-configural’)

displays. Defining what makes the processing of some figures more configural than

others may be a difficult task; we can, however, employ an opposite strategy by finding

out what factors cannot account for the CSE. By constructing a sequential ideal observer

and systematically building into it mechanisms that do not lead to CSE, we can rule out

those mechanisms as possible accounts for configural processes. Candidate mechanisms

to be tested can be spatial frequency filters, attention and eye movements, and more

sophisticated neural mechanisms in the future.

Abstract Relations in Perception and Perceptual Learning

Phil Kellman, University of California, Los Angeles

Among the most important questions in vision, cognitive science, and neuroscience is the

question of how abstract descriptions (such as contour shape) are derived from early,

non-symbolic encodings (e.g., activation of local, oriented, contrast-sensitive units). The

question of abstract descriptions is equally crucial in perceptual learning (e.g., in learning

to recognize new instances of squares or dogs). I will describe recent work on contour

shape that suggests how some abstract relations may be encoded and, time permitting,

work on abstract perceptual learning that suggests how they may be discovered.

Configural coding - a continuum?

Janice Murray, University of Otago

Within the domain of face perception, a definitive characterisation of configural

processing has proved elusive. Two general points can perhaps be agreed upon. Firstly,

the perception of the spatial relations among the components or features of a face

constitutes configural processing. Secondly, the inversion effect - poorer performance in

the processing of inverted faces - is the hallmark of configural processing. On the matter

of the first point, interpretation of the term configural processing has led to a variety of

characterisations that by times appear to confuse rather than illuminate. However, this

apparent lack of consensus may actually reflect the existence of different levels of

processing of configuration when considered within the context of a continuum from

local configural information (e.g., the distance between the eyes) through to holistic

configural processing (e.g., the whole face in which the spatial relations may or may not

be explicitly represented). In my talk I will explore this possibility, linking with inversion

effects in face perception and recognition tasks, and give consideration to the feasibility

of a configural continuum in other domains.

6

Configural Processing 2006: Program

Configural processing is pervasive

Mary A. Peterson, University of Arizona

Some aspects of perception involve processing only features, but many involve

processing both features and the spatial relationships between them; a type of processing

called configural processing. Much research has been devoted to the question of whether

or not configural processing is special for faces. I will discuss examples showing that

configural processing is pervasive in perception and will argue that an important direction

for future research is to understand how configural processing is accomplished.

Prägnanz principle and 3D shape perception.

Zygmunt Pizlo, Purdue University

Perception of 3D shapes critically depends on the operation of a simplicity (Prägnanz)

principle. Simplicity can best be defined by 3D symmetries of an object. Symmetry is

the main (perhaps the only) form of spatially global redundancy, which allows the visual

system to make up for the missing information in the retinal image. When a 2D image of

an object is formed on the retina, the 3D symmetry is broken, but not eliminated. The

approximate symmetries in the 2D retinal shape can be detected and used by the visual

system to reconstruct the 3D shape. As such, the symmetry of a 3D shape percept is an

emergent property. The resulting shape percept is different from the sum of the shape’s

parts in the sense that the symmetry constraint is applied to the 3D shape as a whole, not

to the parts separately. For example, edges and surfaces of a Necker cube are perceived

as 3D because they are edges and surfaces of a 3D symmetric shape. In the case of

complex objects, such as animal or human bodies, 3D parts can be identified by using a

criterion according to which parts have more symmetries than the whole object.

Decisional factors in configural processing

Michael Wenger, Pennsylvania State University

Modal conceptions of configurality stress sensory and perceptual factors, such as

correlations in the coded representations and the rates of processing those representations.

However, consideration of a set of behavioral regularities posited as "signatures" of

configurality reveals that such effects may also arise from changes in response criteria.

Intriguingly, a set of empirical tests of these regularities---using stimuli ranging from

hierarchical forms to words and faces---has documented that such decisional effects are at

work, and may be a regular aspect of processing configural forms. This talk will propose

a set of ways that such decisional effects might arise, including cognitive/strategic

factors, potential influences of correlated noise, and potential effects due to sustained

7

Configural Processing 2006: Program

activation in various cortical regions. Consideration of these and other possible

sources for decisional effects raises questions about the conceptual validity of decisional

influences in models of configural processing.

Wholes, Holes, and Objects in Selective Attention

K Zhou and L Chen

State Key Laboratory of Brain and Cognitive Science

Chinese Academy of Sciences

What is a perceptual object? The topological approach (e.g., Chen, Science, 1982; Visual

Cognition, 2005) holds that topological properties, including holes, constitute a formal

description of perceptual organizations, such as distinguishing figure from background,

and parsing visual scenes into potential objects. According to this approach, a perceptual

object may be understood as something that preserves its topological structure over time.

The topological approach, therefore, ties the formal definition of object to invariance over

topological transformation, and the core intuitive notion of a perceptual object – the

holistic identity preserved over shape-changing transformations – may be precisely

characterized as topological invariants. The topological definition of object implies that

topological changes in holes should be interpreted by the visual system as the presence of

a new object. This prediction was verified by various paradigms, including MOT, precueing, and capture attention. Our fMRI scans further found that changes in holes in

MOT specifically activated the anterior temporal lobe, indicating, together with our

previous fMRI results (Zhuo et al., Science, 2003), that the anterior temporal lobe may

play a major role in the perception of topological invariance as well as of new perceptual

objects.

8

Configural Processing 2006: Program

Map from Hilton Americas Hotel to the Rice campus (violet line)

9

Configural Processing 2006: Program

Detailed map of the Rice campus with X showing Fondren Library

10