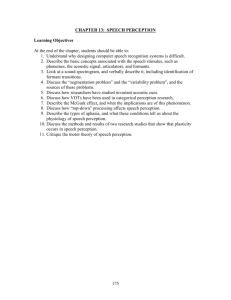

Towards a Unified Theory of Configural Processing

advertisement

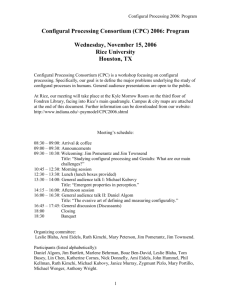

Configural Processing Consortium (CPC) 2007: Program

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Hyatt Long Beach

Long Beach, CA

Configural Processing Consortium (CPC) is a workshop focusing on configural

processing. Specifically, our goal is to define the major problems underlying the study of

configural processes in humans. General audience presentations are open to the public.

Further information can be downloaded from our website:

http://www.indiana.edu/~psymodel/CPC2007.shtml

Organizing committee (listed alphabetically):

Ami Eidels, Phil Kellman, Ruth Kimchi, Mary Peterson, Jim Pomerantz, Jim Townsend.

Meeting’s schedule (Harbor ABC room):

08:30 – 09:00: Arrival (coffee)

09:00 – 09:30: Announcements

09:30 – 10:10: Welcoming and General audience talk I (Phil Kellman)

Title: “A Computational Gestalt Agenda for Perception and Learning”

10:10 – 12:10: Morning session [discussant: Glyn Humphreys]

Speakers (by order of presentation): Jim Pomerantz, Patrick Gariggan, Jim

Bartlett, Alan Gilchrist, Jim Townsend, Viktor Sarris, Glyn Humphreys.

12:10 – 13:10: Lunch (we will provide lunch boxes)

13:10 – 13:50: General audience talk II (Steve Palmer)

Title: “Configural Effects in Aesthetic Preference and Goodness-of-Fit”

14:00 – 16:00: Afternoon session [discussant: Rob Goldstone]

Speakers (by order of presentation): Michael Kubovy, Evan Palmer, Rutie

Kimchi, Zyg Pizlo, Johan Wagemans, Ami Eidels.

Jim Pomerantz presenting the Configural Processing Wikispace.

16:00 – 16:40: General audience talk III (Mary Peterson)

Title: “Biased Competition in Figure-Ground Perception”

17:00 – 17:45: General discussion (Facilitated by Goldstone, Humphreys, and Kubovy)

18:00

Closing

18:30

Banquet (provided; Sea View Rotunda room)

Participants (listed alphabetically):

Jim Bartlett, Boaz Ben-David, Ami Eidels, Mario Fific, Patrick Garrigan, Alan Gilchrist,

Rob Goldstone, John Hummel, Glyn Humphreys, Helena Kadlec, Phil Kellman, Ruth

Kimchi, Michael Kubovy, Mary Peterson, Zygmunt Pizlo, Jim Pomerantz, Mary Portillo,

Jane Riddoch, Viktor Sarris, Jim Townsend, Johan Wagemans

How Do Holistic and Part-Based Perceptual Processes Affect Recognition Memory?

James Bartlett

University of Texas, Dallas

A fundamental question is whether general theories of memory extend to stimuli such as

faces that can be processed in a configural and/or holistic fashion. I consider three

possible answers which are “yes,” “no,” and “partly.” From the last of these questions a

new question emerges: How do domain-specific or domain-related configural-holistic

processes interact with general memory processes of familiarity, recollection, and

memory-editing? A promising approach to this new question is provided by the

“conjunction effect” – the frequent false recognition of new stimuli that recombine the

parts of previously studied stimuli. The conjunction effect is robust with faces, even

naturalistic faces in upright orientation with which configural-holistic processing is

presumed to be the norm. I discuss old and new data on the conjunction effect with

upright faces, inverted faces, objects and verbal stimuli. These data suggest that holistic

and part-based perceptual processes can be distinguished from two general memory

systems that: (a) contribute to hits as well as conjunction false alarms, and (b) control

false alarms in response to conjunctions as well as new items. Remarkably, there are

individual differences in the balance of holistic versus part-based processing, and these

appear independent of individual differences in general memory processes.

Towards a Unified Theory of Configural Processing

Ami Eidels

Indiana University

Capacity and coactivation (e.g., Townsend & Nozawa, 1995), configural superiority

effect (e.g., Pomerantz, Sager, & Stoever, 1978), human vs. ideal observer thresholds

(e.g., Gold, Bennet, & Sekuler, 1999), and Garner interference (Garner, 1974) are but few

of the measures with which we estimate, sometimes define, what we believe to be

configural processing. A unified theory of configural processing should at least attempt to

find relationships among the different measures, perhaps represent them on a common

space. A possible first step is to define a standard set of stimuli, maybe even a standard

procedure, which we shall employ in future research. Then, results from different

experiments and from different labs can be compared. I will discuss each of the measures

and provide a tentative example of possible stimuli. This is just one of several short term

goals that we can specify as part of a concerted effort to define and measure configural

processing.

Efficient Coding of 2D Shape

Patrick Garrigan

Saint Joseph’s University

Implicit in many theories of how the visual system represents shape are the ideas that the

geometric information in stimuli is often complex and some tradeoff between economy

and resolution will typically be necessary. For these reasons it is natural to

apply information theoretic techniques to understanding how shapes might be best

encoded by the visual system, given constraints of noise and capacity. A general theory

of how all the shapes in the world should be optimally encoded is, however, difficult to

establish because the statistics of shape are hard to quantify. Instead, we can look to

behavioral evidence to guide theories of shape encoding. Redundancy in the

representation of shape information can either be minimized to produce the shortest

possible code or incorporated into the representation for error correction in the presence

of noise. I will argue that there is evidence that the visual system’s representations of

shape use both of these techniques.

Gestalt theories and the problem of perceptual errors

Alan Gilchrist

Rutgers University

Decomposition models of perception, such as intrinsic image models of lightness,

Johansson’s model of common and relative components in motion, and Bergstrom’s

analogous model in color, yield percepts that are both the simplest percepts for a given

stimulus and highly veridical. Yet they fail to account for the pattern of errors shown by

humans. Perceptual errors, including both illusions and failures of constancy, are

ubiquitous. And because they are systematic, not random, their pattern must be highly

diagnostic of the visual software. Gestalt theories of lightness advanced by Kardos (1934)

and Gilchrist et al (1999) explicitly and successfully account for errors using concepts of

grouping, frames of reference, and crosstalk between frameworks, but do not obviously

invoke the simplicity principle. How might a gestalt approach based on simplicity explain

the errors? It would seem reasonable to attribute perceptual errors to failures in the

components of a decomposition model, such as an underestimation of the common

component, or a failure of edge classification. Such an approach has not been successful

to date, but might reward further exploration.

Action Relations as a Configural Cue

Glyn W. Humphreys & M. Jane Riddoch

University of Birmingham, UK

Recently we have demonstrated that action relations between objects enable the objects to

be 'bound together' as a single perceptual unit (Riddoch et al., 2003, Nature

Neuroscience). In this talk we will evaluate the factors that lead to this perceptual binding

between objects in action relations. We ask whether the effects are automatic, whether

they are contingent on familiarity, on the presence of covert motion between the objects,

and whether the bound unit operates in any way like a perceptual configuration. The

evidence points to action relations being an important cue for configural coding.

A Computational Gestalt Agenda for Perception and Learning

Philip J. Kellman

University of California, Los Angeles

Basic issues advanced by the Gestalt psychologists almost a century ago still

define crucial priorities in cognitive science and neuroscience. A key set of issues

involves elements, relations, and abstraction in perception. I will highlight this issue in

vision models, where a crucial challenge is relating early, non-symbolic encodings (e.g.,

activation of local contrast-sensitive units) to abstract descriptions and relations (such as

contour and object shape). A related set of Gestalt issues involves seeing structure and

“insight,” pointing to crucial but mysterious links among perceiving, thinking, and

learning. I will show how these issues relate to efforts to understand abstract perceptual

learning. I will also argue that perceptual learning is a neglected dimension of learning in

instructional contexts, and that it is a major component of learning even in high-level,

symbolic domains.

How do we make progress in these areas? I will suggest that many problems

center on identifying a “grammar” of relational encoding that begins at early processing

stages. Some of this recoding is automatic and constrains what can be perceived and

learned. Other recoding allows synthesis of new relations with experience, allowing us to

discover even higher-order structure. Characterizing such a grammar of perception and

learning will be difficult, but will benefit from grounding in ecological analyses (as in the

work of James Gibson and David Marr). Likewise, I will suggest that both computational

understanding and instructional utility will advance from merging Gestalt ideas about

structure and “insight” with perceptual learning concepts (as in the work of Eleanor

Gibson).

What does it mean that “the whole is different from the sum of its parts”?

Explorations with face discrimination

Rutie Kimchi & Rama Amishav

University of Haifa

One way to capture the Gestaltists’ tenet that “the whole is different from the sum of its

parts” is that a whole is qualitatively different from the complex that one might predict by

considering only its parts. We report recent attempts to examine the implications of this

notion of configural processing (e.g., processing dominance of configural properties) in

the context of face perception, given that configural processing is considered to be the

hallmark of face perception. In doing so, we address the following three questions: 1)

Does the discriminability of face components (i.e., eyes, nose, mouth) determine the

discriminability of the whole face? 2) Is the discriminability between faces that differ in

configural properties (spatial relation between components) easier than between faces

that are similar in configural properties, regardless of the discriminability of the

components? 3) Is there perceptual dependence/independence, as indexed by selective

attention (Garner interference), between components, and between components and

configural properties? The implications of behavioral data pertaining to these questions

will be discussed.

A possible link between conjoined grouping principles AND

{weak fusion OR stochastic integration}

1

Michael Kubovy1 & Sergei Gepshtein2, 3

Univ. of Virginia; RIKEN Brain Sciences Inst. [Wako-shi, Japan]; 3Salk Institute

2

It has recently been discovered that when two grouping principles (proximity and

similarity) are conjoined, their joint effect on grouping strength is an additive

combination of their separate effects on grouping strength, and that across observers

there is a high negative correlation between their contributions. We argue that this is just

what would be expected from the application of a maximum-likelihood estimation

(MLE) approach -- commonly used to describe phenomena of sensory integration -- to

grouping. But the evidence of negative correlation is also consistent with a decision

strategy known as stochastic integration, by which observers use one factor of grouping

at a time and do so probabilistically.

Perceiving Dynamically Occluded Objects

Evan Palmer

Wichita State University

In a world of mobile objects and observers, accurate perception of shapes requires

processes that overcome fragmentation in space and time. When an object moves behind

an occluding surface with many apertures, perception of its shape is remarkably robust

and precise. This accurate shape perception occurs even though fragments of the

dynamically occluded object appear at different times and places. We developed the

theory of Spatiotemporal Relatability to account for observers’ perception of dynamically

occluded objects. Spatiotemporal Relatability proposes that when parts of objects move

behind an occluding surface, their shapes and positions continue to be perceptually

available even though they are physically occluded. The positions of persisting but

occluded fragments are updated over time in accord with the object’s observed velocity

so that visible and occluded fragments can be connected together to form units. We

propose the dynamic visual icon representation as the mediator of these persistence and

position updating processes. This elaboration suggests that the visual icon may be more

versatile than previously suspected. Under this new view of object completion, motion is

an integral part of all shape perception processes and static images are merely a special

case in which velocity is equal to zero.

Configural Effects in Aesthetic Preference and Goodness-of-Fit

1

Stephen E. Palmer1, Jonathan Gardner1, & Stefano Guidi2

University of California, Berkeley; 2University of Sienna, Italy

We will report on two related projects that concern experiential dimensions that appear to

be dominated by similar configural factors. The first concerns aesthetic response to the

spatial configuration of simple images containing one or more familiar objects within a

rectangular frame. Our results show the effects of several powerful, configural variables,

including a "center bias" in lateral placement, an "inward bias" in lateral placement, and a

"lower bias" in vertical placement. The second concerns people's experience of the

"goodness of fit" for a probe shape ( e.g., a small circle or triangle) within a surrounding

rectangle (cf. Palmer, 1981). Such ratings also reveal the importance of the center of the

frame and pointing inward within the frame, as well as striking evidence for the role of

symmetry and balance in spatial composition. The relation between these two lines of

research will be described in terms of expectations generated by the structure of the

rectangular frame and its relation to the structure of the object(s) it contains.

Biased Competition in Figure-Ground Perception

Mary A. Peterson

University of Arizona

To perceive configurations, one must perceive shaped entities, or "figures," yet the

processes producing shape perception are not yet understood. Progress has been

hampered by three mistaken assumptions (1) figure-ground segregation is an early and

separate stage of processing, (2) this early stage produces a coupled output of shape and

relative distance, and (3) there exists a border ownership process. I will review

behavioral and neurophysiological evidence indicating that figure-ground perception

results from competition between two candidate shapes that might be seen; that

suppression is an integral part of this process; and that suppression can spread from one

part of the visual field to another. I will close by proposing that figure-ground perception

lies at one end of a continuum of processes explained by the biased competition model of

attention.

Symmetry and Shape

Zygmunt Pizlo & Tadamasa Sawada

Purdue University

It is quite well established that human observers can quickly and reliably detect

symmetrical patterns on the retina. Symmetry detection is important because (i) many

objects "out there" are symmetrical, and (ii) symmetry is a form of redundancy.

However, a retinal image of a symmetrical object is itself almost never symmetrical.

Instead, it is "skewed symmetrical". Can human observers detect skewed symmetry? The

answer is "YES". The ability to detect skewed symmetry is of fundamental importance

for shape perception because the application of symmetry constraint to a single 2D retinal

image leads to an accurate recovery of a 3D symmetrical shape. We will argue that the

visual system uses symmetry not as a form of redundancy, but rather as a rule of

perceptual organization.

The Experience Error Revisited

James R. Pomerantz

Rice University

In psychological research, nothing matters more than understanding and describing the

stimulus correctly. Whether it entails only a simple visual pattern on a display or

multisensory, 3D scenes with assorted objects and agents, an accurate and complete

description is necessary both for scientific communication –allowing others to replicate

our studies – and for helping us understand what parts of a stimulus are effective in

engaging cognition and behavior. We sometimes portray our stimuli inaccurately and

commit the experience error, however, by describing the stimulus as we see it rather than

how it may actually be. In essence, we confuse our perceptions of the world with the

stimulation we receive from it, wrongly attributing perceived structure to the proximal

stimulus. By presuming the stimulus is what we see it to be, we confuse stimuli with

responses, with our percepts. We illustrate this phenomenon with several common

examples, show why they matter, and suggest ways in which research and theory in areas

including the perception of objects and wholes may be advanced by addressing the error.

Transposition, Relation, Relational Perception, and Comparative Psychophysics

Viktor Sarris

Frankfurt A.M., Germany

The gestalt premise of relational perception is inherent in all kinds of „transposition“

(relational perception), both in humans and other animals. This is demonstrated in my

talk on my comparative frame-of-reference experiments with either two-stimulus

(unidimensional) orfour-stimulus (twodimensional) postgeneralization context-test

procedures. For instance, in the unidimensional case both the animal and human subjects

showed marked and lawful psychophysical context effects, at least within a certain

stimulus range (testing-the-limits approach); however, in the multidimensional case (fourstimulus paradigm) the respective transposition behavior followed very different response

rules for the different species investigated (cf. Sarris, Relational psychophysics in humans

and animals: a developmental-comparative approach. Psychology Press, London). Of

our main interest here are the crucial, still unsolved problems as related to Questions 1 &

2, namely the issues of the relational processing involved and its connection to

“configural” (integral vs. separable dimensions) responding: How is, or may be, their

age-dependent and comparative analysis to be conceived by some relevant predictive

quantitative modelling and explanatory theorizing? In this context the role of “similarity”

in multidimensional configural processing needs to be emphasized.

Emergence Pictured through Dynamics

James T. Townsend

Indiana University

The concept of emergence has been challenging to define in a precise manner. Some

attempts at general definition seem vague and un-resolvable. Ambiguous figures and

hidden figures are reasonable exemplars which deserve the term. I propose that one

reasonable approach to this concept rests in the general field of mathematical dynamics.

Certain concepts that appear meaningful in the context are discussed.

On groups, patterns, shapes and objects: The many ways in which multiple elements

interact

Johan Wagemans

University of Leuven, Belgium

Perceptual grouping, figure-ground organization, shape perception and object recognition

are all domains in which configural processing plays a role but theoretical synthesis has

been hampered by the diversity of stimuli and experimental paradigms. We have

attempted to study interactions between different component processes and to facilitate

cross-domain comparisons of results by using different kinds of stimuli consisting of

multiple Gabor patches. In Claessens and Wagemans (2005, Perception &

Psychophysics, 67, 1446-1459), we have investigated the interactions between proximity

and alignment in so-called Gabor lattices (analogous to the Kubovy & Wagemans dot

lattices but with Gabor patches instead of dots). In a second line of research (with Bart

Machilsen), we have asked observers to discriminate open contours (“snakes”) from

closed contours (“shapes”) consisting of Gabor elements against a random background,

and we have compared symmetric to asymmetric shapes. In a third line of research (with

Geir Nygård), we have presented Gabor patches on the contour and on the interior

surface of outlines derived from objects and we have compared detection, discrimination,

and identification. In a fourth line of research (with Lizzy Bleumers), we have asked

observers to localize shapes (contours with Gabor elements) and we have compared

upright to inverted object outlines. I will discuss the many different kinds of interactions

between local elements in these different contexts.