1986965 (2001 Census)

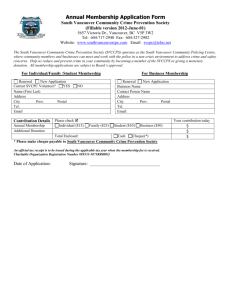

advertisement