The challenge of unilateral measures vs. uniform rules

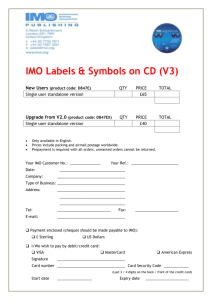

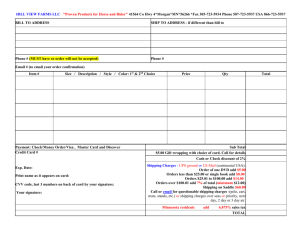

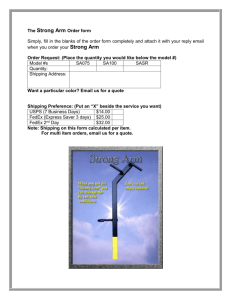

advertisement

International Seminar The Law of the Sea The challenge of unilateral measures vs. uniform rules hosted by Ince & Co London, 25 April 2007 The Shipping Industry’s views by John C. Fawcett-Ellis, General Counsel, INTERTANKO Judge Wolfrum, distinguished guests and industry colleagues. Firstly, our thanks to Ince & Co for this initiative and for kindly hosting this seminar and for inviting INTERTANKO to present is views on this important subject. We very much appreciate this invitation to present our views on the important subject of ensuring that the shipping industry is governed by international laws and regulations 1 We also welcome this opportunity to highlight concerns over recent laws which have not followed international conventions. We are keen to ensure that there is adequate access to judicial fora to examine the validity of new regulations which might overlap with international conventions. Today’s seminar/discussion forum is therefore extremely welcome and timely. One of INTERTANKO’s core principles has been to seek international and uniform laws for an industry that is truly global. When necessary we have take action to stand up for this principle. Most notable was INTERTANKO’s victory in the US Supreme Court in 2000 over regulations which the State of Washington tried to introduce, which conflicted with Federal regulations on the safety of ships. 2 The Shipping industry needs regulations that are. - International - Uniform - Sensible and practical in the sense of achieving their objectives What factors influence new regulations? - The need to enhance safety / protect lives - A call for more exacting standards to protect the environment - Advances in technology - Political demands - Demand from the user/consumer - Industry best practice 3 Good regulations should: - Be carefully thought through and not be a political knee jerk reactions - Balance the views of all stakeholders - Take into account the existing regulatory environment So what about some recent examples of regulations of the shipping industry? The ISM and ISPS codes are good examples of practical international regulations for the shipping industry. On the other hand the EU Ship Source Pollution Directive, which seeks to criminalise accidental pollution is a distinctly politically motivated piece of legislation. It is well known that the pressure for this new piece of regulation resulted from the two serious pollution incidents involving the vessels: Erika and Prestige. 4 On 6 December 2002 less than three weeks after the Prestige had sank the EU’s Transport and Telecommunications Council welcomed. “the intention of the Commission to present a proposal to ensure that any person who has caused or contributed to a pollution incident through grossly negligent behaviour should be subject to appropriate sanctions.” On the 5th of March 2003 the EU Commission published its first draft of the proposed Directive to criminalise accidental pollution. There had been no prior consultation with the public or interested parties. The Prestige incident had not been properly investigated nor had any meaningful conclusions been made. The Draft Directive was considered by the EU Parliament and its Transport Committee. That Committee proposed various amendments because they had recognised that the Directive conflicted with the 5 international regime laid down in MARPOL. The improvements suggested by that Committee were overturned by a subsequent “Common Position” adopted by the Council of Ministers. Industry including INTERTANKO were concerned about the Directive right from the start. We were also concerned that the Directive was at odds with the international regime laid down in MARPOL and UNCLOS as regards criminal liability for pollution incidents. The introduction of criminal culpability for “serious negligence” was a particular concern. Naturally we were concerned at the affect the Directive would have on the recruitment and retention of good seafarers. 6 Shipping is an international industry, which for reasons long recognised by the international community is best regulated on a global basis by uniform international laws. National or regional measures which deviate from these laws threaten to undermine the international system of regulation. Uniform standards and their enforcement play a part in maintaining a level playing field of fair competition in worldwide maritime commerce. The alternative would be a plethora of conflicting national regulations resulting in commercial distortion and administrative confusion which would compromise safety and the efficiency of world trade. For these reasons the international community has long agreed that shipping as a global industry is best regulated by uniform international laws. These are developed principally at the IMO. The IMO has 166 Member States and legislation developed under its auspices is the product of the pooled experience and expertise from throughout the international community, including all EU 7 Member States. Industry associations such as INTERTANKO have observer status at the IMO and participate actively in its deliberations. MARPOL is both an international set of regulations and also a uniform set of rules. The shipping industry needs both these elements for there to be global standards. It is worthwhile to recall the Preamble to MARPOL; the contracting parties considered that the object of the convention “may best be achieved by establishing rules of universal purport”. A similar view is taken in the Preamble to SOLAS which provides that contracting states are desirous of: “establishing in a common agreement uniform principles and rules…” The quality of the IMO legislative process is high, given the long experience of the Organization, the expertise and other resources at its disposal, and the broad support normally enjoyed by regulations 8 made under its auspices. For example, some 135 States are parties to MARPOL Annexes I & II. So it is truly international and the rules that it lays down are to be applied uniformly; they are a common standard to be followed. One of the balances which is struck by a convention such as MARPOL is a compromise between the interests of coastal and flag states, Flag states and industry interests undertake higher levels of regulation on the basis these are to be uniform rules, and that coastal states for their part will restrain themselves from legislating in terms at variance with these rules. Amendment of these regulations has often become appropriate in the light of experience and improvements in industry standards. Like other IMO conventions MARPOL incorporate a tacit amendment procedure which is an expeditious method of making changes. However it is quite another matter if States by-pass this procedure and adopt new rules of their own accord. This is to 9 repudiate their side of the international agreement they signed up to and defeats the very purpose for which it was made. The conflict between the EU Ship Source Pollution Directive and MARPOL is not inadvertent, but results from the fact that the Directive expressly refers to the Convention and purports to alter or exclude the effect of certain of its rules. It therefore constitutes a direct challenge to the supremacy of the Convention, and to the authority of the IMO as the competent global regulatory body. A broad coalition of the shipping industry comprising: INTERTANKO, INTERCARGO, the Greek Shipping Cooperation Committee, the International Salvage Union and Lloyd’s Register have brought proceedings before the European Court in order to test the legality of the Directive. 10 Whatever the outcome, these proceedings should be welcomed by anyone committed to global regulation of shipping. They should also encourage governments to examine more closely the existing international regime before seeking to legislate in overlapping areas. The Directive is not an isolated example of governments taking measures in the maritime sector which overtly challenge the authority of international law, and which test the will of the international community to enforce it. After the Prestige incident naval vessels from Spain and Portugal forced single-hulled tankers carrying heavy grades of oil to remain not only outside their territorial waters but also outside their exclusive economic zones. Those vessels were trading lawfully and their right of innocent passage through the territorial water of the States concerned was violated. Though the Government of Norway protested to Spain, no response was received. 11 Another recent example is the making of pilotage compulsory in the Torres Strait. The Torres Strait is recognised under UNCLOS as an international strait where vessels have the right to transit the strait with the coastal states only have limited rights to control that transit. In 1991 the IMO recommended that all tankers should use Australia pilotage services when navigating the Torres Strait. Around 2004 Australia sought to gain approval from the IMO to make the pilotage compulsory. MEPC in July 2005 reaffirmed its position that the pilotage could only be recommendatory. The US stated that there was no legal basis for the pilotage to be mandatory. Other States supported the US position and Australia did not object to it. Despite that from 6 October 2006 Australia made pilotage compulsory in the Torres Strait. 12 This matter has generated diplomatic exchanges and much comment from industry and international lawyers. There are few, if any, who view Australia’s actions to be within the bounds of international law. So has anyone sought to bring the matter before the courts for a declaratory judgment on the issue? No; once again there is a reluctance to resort to such action. The Hamburg tribunal would be a natural forum for this dispute, but as States have to bring the action there is a clear lack of appetite for a confrontational approach between States. So the status quo remains and Australia have advised that the regulation stands and will be enforced. A further example of a regulation which many distinguished commentators and industry believed transgressed international law is the Canadian law which was known as Bill C15 before it entered into law. This law again seeks to criminalise accidental pollution within Canada’s EEZ. Here the burden of proof is reversed with a 13 polluter guilty unless innocence can be proved. This is a clear departure from the regimes of MARPOL and UNCLOS. Was action taken to challenge this law? Again the answer is no. It has entered into force without challenge. Generally only States have the standing to take other States to court for breach of treaty obligations, but in the maritime sector they have seldom seen any public interest in doing so. Normally the impact is limited to private parties who do not have access to the competent international tribunals. This not only means that well-founded grievances may go without remedy; it can also lead to governments taking measures which are guided less by international law than by the precedent of other states acquiescing in departures from it. At its best this engenders uncertainty as to where people stand and at its worse it undermines respect for international legal order. 14 So it often falls on industry associations to act as watchdogs on international law and to launch proceedings. There is a need for an easier mechanism which new laws can be tested to ensure they do not conflict with international law. There is need for a process that is non confrontational that will ensure a methodical review of the relevant laws and regulations. We welcome further discussion on what solutions there might be. Thank you for your kind attention. JFE 25.4.07 15 16