economic development under stalin

advertisement

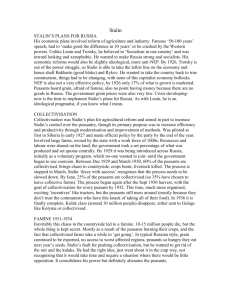

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT UNDER STALIN Problems facing the USSR in 1929 Russia needed to import capital equipment (machinery) from overseas, to facilitate industrialisation. Since the Western nations were unwilling to lend Russia money, the foreign exchange would have to be earned, via exports. Russia had only one exportable product – agriculture. However, agricultural production was inadequate to feed Russia’s growing urban population, let alone provide a surplus for export. There were food shortages in the towns and cities. NEP was benefiting the wealthy peasants (kulaks), who were never likely to support the socialist ideology of the Bolsheviks. Many party members were uncomfortable with NEP, because it was really just rural capitalism. Stalin also feared that Russia was very vulnerable to external attack. If it did not industrial quickly, the Revolution could be swept aside by foreign invaders – particular Germany, which was lurching to the right as the Depression hit. In addition, Stalin felt the country needed to industrialise to strengthen the party’s support base, by creating a large working class. Once this was achieved, the regime’s remaining enemies (such as the kulaks) could be eliminated. Stalin’s plan for economic development Stalin concentrated most of the nation's resources on heavy industry. This meant very few consumer goods were produced, giving peasants little incentive to increase production (since there was nothing to buy with the income they received). To prevent the peasants from reducing production (in response to the lack of goods to buy), Stalin collectivised the land, forcing the newly formed collectives to meet strict production targets. To ensure that resources were directed to the areas of need, NEP was replaced by command socialism, with all industry nationalised and market mechanisms replaced by a series of five year plans. Imports were reduced to a bare minimum – mainly capital equipment. Finally, a reign of police terror was unleashed in order to deal with the unrest resulting from collectivisation. Over 20 million people died during this period – some because they refused to hand over their produce and livestock (they were shot), others because they did hand over their produce (they starved). Industrial development The basis of Stalin’s industrialisation plan was the Five Year Plan – a formal expression of the major goals and priorities of the government. These goals included high rates of economic growth, priority to heavy industry (especially fuel, steel and machine building), military technology, scientific and technical education and training, and economic self-sufficiency. The core of a Five Year Plan (FYP) was the investment plan, because it was seen as the key to growth. Under the First Five Year Plan (1928-33), steel production was to rise by 200 percent and electricity production by 400 percent. While these targets were not met, industrial production did increase dramatically. By 1933, output levels were four times that of 1913. Production of oil and gas rose by 130 percent between 1929 and 1938. Over that same period, production of coal and iron ore rose by 230 percent each, steel by 267 percent, electricity by 540 percent, and chemicals rose by almost 1000 percent. This was a significant achievement, given that in the Western nations, industrial output had fallen to below the 1913 level (as a result of the Great Depression). Workers were encouraged to raise their production levels by being paid bonuses. Propaganda (such as the Stakhanovite movement) was also used for this purpose. Terror was also used, with unproductive workers or managers being shot. Forced labour was also used, particularly for projects which were deemed to be very difficult and/or dangerous. Despite the increase in wages and living standards, wages were kept low so that the surplus could be reinvested in industrial plant. Collectivisation of agriculture Reasons for collectivisation Stalin believed that industrialisation would have to be financed by agricultural surpluses, which meant squeezing (ie. exploiting) the peasants. But he feared that they might react to high taxes by reducing production. The solution was to force the peasants to produce by organising them together into collectives, thereby denying them the opportunity to withhold production. Stalin believed the collectives would be highly efficient, since they could utilise the machinery produced by heavy industry. He also knew that collectivisation would be highly disruptive, with many peasants driven off the land. These people would be forced into the cities, becoming the labour force for the newly created industries. Ideologically, Stalin believed the peasants were reactionaries, who would never support the Bolsheviks unless divested of their private property. Given that they represented 80 percent of the population, they resistance had to be crushed. Collectivisation was seen as a means of fostering socialism in the countryside. Finally, collectivisation would allow the state to take control of the rural population, preventing the peasants from threatening the regime by withholding agricultural production. This coincided well with Stalin’s desire to increase his own power in Russia. The process of collectivisation Stalin’s plan was to eliminate private ownership of agricultural land, and replace it with a system of state-owned and collectively-owned farms. His initial intention was to do this gradually (with only 20 percent of the land to be collectivised by 1933), so as to avoid excessive disruption (which would reduce agricultural production). However, in January 1930, he decided to implement the entire plan immediately. Hence, by March of that year, 50 percent of all peasant farms were collectivised. The poorer peasants tolerated collectivisation because they had little land and few animals to lose. But the wealthier ones (the kulaks) bitterly opposed it. These farmers had supported NEP and refused to accept its abandonment. Many kulaks refused to part with their land, and reacted to government pressure by reducing production to subsistence levels. Many also burned their farms and killed their cattle in preference to handing them over to the government. Stalin’s initial reaction was to call a halt to the collectivisation process, fearing it was having serious economic consequences. But when large numbers of peasants abandoned the collectives and returned to private farming (the proportion of collective farms falling from 50 percent to 21 percent by August 1930), Stalin looked for new enemies to blame. Stalin decided that the kulaks were the reason for the failure of collectivisation, because they were a counter-revolutionary force. He therefore decided to eliminate them as a class in society. Their possessions were confiscated and they were prevented from joining collectives. Those who continued to resist were exiled to Siberia or shot; whole villages were burned. The result was a precipitous decline in agricultural production. The number of sheep and goats fell from 146 million in 1928 to 42 million in 1933. Cattle numbers fell from 70 million to 34 million over the same period. Because of the fall in agricultural production, the USSR was hit by famine in 1932-33. The worst hit region was the Ukraine, where resistance to Soviet rule had been strong. Stalin was furious that the area had failed to meet its grain requisition targets, and decided to use the famine as a means of punishing the people. All grain was confiscated by the state, and troops were stationed on the borders Ukraine’s borders, to prevent people from leaving. The peasants were then left to starve. About 7 million people died during the famine, 5 million of them in the Ukraine. Total agricultural production did not recover to the 1928 level until 1938. The Stalinist system of agriculture State farms (sovkhoz) were run like industrial enterprises. This meant they were state owned, hired their workers, and were subject to rigid production plans. Collective farms (kolkhoz) were created by amalgamating the land of between 50 and 100 families. They were jointly owned by their members, but had to produce what they were told, and to deliver a fixed quota to the state each year. The rest they could keep, after allowing for reinvestment. Individual peasants were paid in kind and/or cash according to how hard they worked. Each region had a Machine Tractor Station, which maintained the equipment on neighbouring collective farms. In 1935, Stalin permitted peasant households to work private plots of land (up to one acre in size) and sell the produce on the market. These plots represented only 3 percent of agricultural land, although they accounted for a quarter of all sales. This was due partly to the fact that they were worked more intensively (since all the resultant produced could be kept), and partly to the fact that they produced higher value products (like meat, eggs and milk). By 1936, all resistance to Stalin's will had been crushed and the economy completely transformed – so much so that Stalin could declare that Russia was now fully socialist. Economic achievements of the Stalinist system It is difficult to get accurate figures on Soviet economic performance. However, it appears that the Soviet economy grew at between 4.5 and 6.3 percent between 1928 and 1960. When the destructive effects of the Second World War are discounted, the growth rate was between 5.5 and 7.7 percent. Not surprisingly, industrial output grew by the greatest amount (steel output, for example, grew by 2,000 percent). The big rise in industrial output was a product of three factors: the vast investment in science and technology undertaken during this period; the achievement of economies of scale utilising relatively unsophisticated technologies; and the decision not to emphasise consumer goods, which allowed investment spending to reach extremely high levels. However, the successes in industry were not matched by that of agriculture. Production in 1953 was barely above the 1928 level. As such, agriculture did not generate the levels of capital expected by Stalin and Preobrazhensky. Had it done so, Russia might have been able to develop at an even faster rate, or provide a bigger rise in living standards than was experienced during the Stalinist period.