Now is the time for all good men to come to the

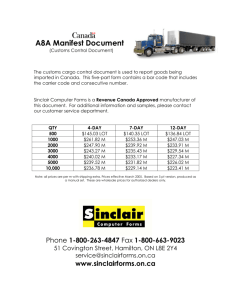

advertisement