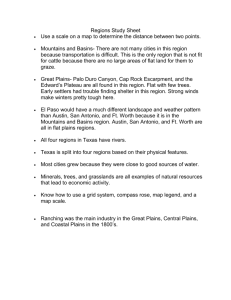

Wages Are Climbing in the Great Plains

advertisement

Wages Are Climbing in the Great Plains --Low In-Migration Creates A Labor Shortage By Scott Kilman 08/05/1997 The Wall Street Journal Page A2 (Copyright (c) 1997, Dow Jones & Company, Inc.) Newly minted college graduate Richard Darrell Jr. got a big raise for being in the right place at the right time -Omaha, Neb. Armed with a degree in finance, the 22-year-old Creighton University alumnus accepted an $18,500 salary at a local software company. Then came an unsolicited phone call from First Data Resources -- a financial-services business expanding in Omaha -- offering $10,000 more. The Labor Department recently reported that wages and salaries for U.S. workers rose, on average, a scant 0.8% in the second quarter, despite low unemployment and a tight labor market. But wages are jumping across the Great Plains. A decade-long economic expansion has created a labor shortage, and there aren't many more people to draw into the work force. In Minnesota, 88% of the population between the ages of 16 and 64 is in the labor force, compared with 79% for the U.S. In South Dakota, 71.3% of women with preschool children are working, the highest level of any state. That's forcing businesses ranging from slaughterhouses to computer makers to sweeten wages and benefits more quickly than the national average. "Wage gains on the Plains are the highest in the country," says Sung Won Sohn, chief economist of Minneapolis-based bank-holding concern Norwest Corp., who expects compensation across the region to swell by an average 5% to 7% this year. But will the wage increases taking place on the Plains spread throughout the nation, setting off an inflationary spiral? Few economists think so. Wages on the Plains are jumping in large part for a unique reason -- too few people are willing to relocate to a region known for flat lands and extreme weather. Labor shortages in other regions have often prompted large migrations, such as Northeasterners moving South or Californians moving to the Pacific Northwest. The movements help to eliminate shortages and act as a natural check on wages. But in-migration to the Plains states has been slow. Also, wages in the Plains states, while currently on the rise, remain lower than in many other states, another factor that makes it difficult for companies to woo workers from outside the region. Average annual wages in South Dakota, for example, are roughly $20,000, the lowest in the nation. In comparison, workers in California have average annual wages of about $31,000. With that gap, it's not surprising that relatively few people are moving from California to South Dakota for the jobs. "I don't think we can draw a connection between what's happening on the Plains now and what will happen elsewhere," says Charles Krider, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Business Research at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. In Milan, Mo., starting pay at the Premium Standard Foods pork plant is rising 13% to $8.50 an hour. The other big employer in town -- a ConAgra Inc. chicken processing plant -- lifted beginning wages this spring by 9% to $6.80 an hour, according to state employment officials. After years of falling far behind, even meatpacking employees are beginning to catch up. IBP Inc., the nation's biggest meatpacker, is lifting hourly wages at its Iowa plants as much as $1 an hour. Manufacturing wages in South Dakota are up 6.1% this year. Some Minneapolis retailers are raising starting pay as much as 10% this year. And competition for laborers is forcing farmers in Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas to pay 12% more for field and livestock workers, according to an April survey by the U.S. Agriculture Department. In the hottest spots on the Plains, wage increases are beginning to lift some consumer prices. The average price for an existing $200,000 home in Sioux City, Iowa, for example, rose about 8% last year. That's where personalcomputer direct marketer Gateway 2000 Inc. has doubled its local work force to 5,018 over the past 31 months. The demand for housing is so strong that Bart Connelly moved his construction business to Sioux City from Dallas last year. "There's no ocean and no mountains here, but we like the schools and low crime," says the 36-year-old Iowa native, who is building seven homes and a townhouse. "Plus, I'm busier than ever," he adds. But there are signs that the Plains economy is beginning to cool. Roughly 53,200 jobs were created in Minnesota in 1996. With the vast majority of able-bodied persons in the state already working, the expected net migration of 20,000 people to Minnesota this year just isn't enough to keep payrolls expanding at the same pace. Minnesota's state economist, Thomas F. Stinson, expects personal income there to grow 4.5% during the 12 months ending next summer, compared with the blistering 7.8% for calendar 1996. Likewise, the number of new jobs is expected to slow to 37,000. "Our growth is limited by the ability to find workers," he says. In South Dakota, where a strong farm economy helped lift total personal income 10.4% last year, the long-stagnant population is growing again. However, with a high percentage of the population already working, the number of jobs is growing less than 2% this year, compared with 3.5% annually during the first half of the 1990s. Likewise, nonfarm-income growth appears to be slowing to about 5% this year. "We've run out of farm wives" to hire, says Randall M. Stuefen, research director of the Business Research Bureau at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion. "Labor is probably our most limited resource." To find skilled workers, a tool maker in Lake Preston, S.D., is taking on high-school students as apprentices, and promising new workers an 8.7% raise after six months. "It's real easy for people to jump around," says Gene Paul, plant manager. "A lot of applicants have had four jobs in the past year." In Nebraska, where thousands of jobs are going unfilled, hourly wages for marketing positions at some companies jumped by low double digits in the first quarter, compared with the fourth quarter of 1996, according to a state survey. Ernest Goss, an economics professor at Creighton University in Omaha, expects job growth in Nebraska to slow to 2.1% this year from 2.4% in 1996. "We could grow 5% to 6% if we had adequate in-migration," he says.