2 A portfolio approach to classify logistics services

advertisement

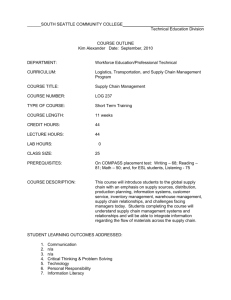

19th International Conference on Production Research A FRAMEWORK TO ANALYZE THE ORGANIZATION OF THE LOGISTICS SERVICES N. Bellantuono1, I. Giannoccaro, P. Pontrandolfo Politecnico di Bari, Italy Abstract This paper concerns the sourcing strategy of the logistics services and the organization of the buyersupplier relationships. It aims at identifying the sourcing strategy for the different types of logistics services and to design the proper way to organize the buyer-supplier relationships. Previous literature usually addresses this topic, by adapting the general portfolio models to the logistics services with no regard for their specific nature. In addition, it seems that such models are not adequate to identify appropriate sourcing strategies as well as to suggest how to manage the attendant relationships. Therefore, on the one hand the paper defines an original portfolio model specific for the logistics services and then classify them into the resulting portfolio matrix. On the other hand, five different forms of governance of the logistics services ranging from market to hierarchy are identified, by means of three dimensions, i.e. physical, strategic and organizational. The forms of governance suitable to the different types of the logistics services are suggested. In particular, specific emphasis is given to intermediate forms of governance such as the organized market based on the fourth party logistics provider. This form of governance seems more appropriate for the case of the consolidated logistics services. Keywords: Logistics services, forms of governance, portfolio models, organized markets, fourth party logistics. 1 INTRODUCTION Changes in the competitive scenario and the increased use of the outsourcing have caused a great interest for the design and the management of the supply relationships of the logistics services [1]. Different models of buyer-supplier relationships for the logistics services exist. A firm needing a logistics service adopts an arm’s length approach with her logistics service provider (LSP) if she purchases the service on the market every time it is needed. This model is characterized by spot transactions, short-term arrangements, limited information sharing, and focus on efficiency. It does not lead to long-term strategic advantage [2]. At the opposite side, a firm and her LSP establish a partnership approach when they become long-term strategic partners, namely have mutual trust and share risks and rewards, exchange operating as well as financial information, and make joint investments in facilities [3]. [4] underline three dimensions of the involvement required to firms so as to establish a partnership: (i) the coordination of operational activities, such as production planning and deliveries; (ii) the adaptation of resources to the requirements of the partner, for instance by joint product development and dedicated processes; (iii) a close interaction among individuals, so as to increase commitment and mutual trust. Since the aforementioned dimensions are costly to be assured and expose actors to a wide range of vulnerability [5], not all buyer-supplier relationships should be managed by using partnership. However, a properly chosen partnership assures an increase of the effectiveness – in terms of level of service, flexibility, and agility – as well as the efficiency – in terms of cost reduction – for both actors [6]. Recently, two new models that are coherent with a partnership approach are emerged, namely the network with third-party logistics (3PL) and the network based on a fourth-party logistics (4PL). They differ in the degree of actors’ involvement and in the wideness of the 1 relationship. The 3PL provider is a LSP that cooperates with a firm in a specific logistics field, understanding her needs, developing a solution, and providing the service. The 4PL provider, in turn, is an integrator that designs, builds and runs comprehensive logistics solutions, by using capabilities and resources from himself and other organizations, including both buying firms and other LSPs. This paper intends to analyze the problem of choosing and designing the proper buyer-supplier relationships for the logistics services. While this topic has been more deeply investigated as to the physical items, it is largely neglected referring to the services. A classification of the logistics services is provided by using a portfolio approach [7]. This permits not only to classify the logistics services, but also to identify the sourcing strategies. The proposed portfolio matrix is based on two dimensions, i.e. the strategic importance of the logistics services and the complexity of the supply markets. However, the portfolio approach is not adequate to identify the appropriate sourcing strategies of the logistics services as well as to suggest how to manage the attendant buyersupplier relationships. In particular, as to the paper aim, the main weaknesses of this approach concern: the focus on the classification of the products/services rather than on the organization and the management of the buyersupplier relationships; the absent consideration of the interdependencies between products/services, and the use of a dyadic (buyer-supplier) rather than a supply chain (SC) point of view [8]. Such limitations are exacerbated in the case of the logistics services, because of the recent trend to buy more complex and consolidated logistics services. Thus, this paper intends to overcome these limitations. To pursue this aim, a framework that classifies the different models of the buyer-supplier relationships is provided by focusing on the physical, the strategic, and the organizational dimensions. In developing such a Corresponding author. DIASS, Politecnico di Bari, viale del Turismo,8 – 74000 Taranto, Italy (tel.: +39 0805964218; fax: +39 0805964303; e-mail address: n.bellantuono@poliba.it). framework, the SC is assumed as unit of analysis. In particular, the considered SC is made up of the buyers of a product, their suppliers, both expressing logistics service demand, and the LSPs. Such a framework specifies the way to organize and manage the SC relationships. In This way, the SC as a whole is considered and the interdependencies are taken into account. The proposed framework identifies five different forms of governances of the specified SC, ranging from market to hierarchy. A key contribution of the framework concerns the definition of a new form of governance that has been conceptualized and applied in SCs of tangibles but never considered in the case of logistics services, namely the organized market [9]. Finally, for each class of the logistics services the specific form of governance that should be adopted is suggested. While the market seems to be appropriate for the not critical and leverage logistics services (e.g. loading, unloading, picking, and material handling), the network with 3PL and the organized market are suitable for the strategic services. In particular, the main benefits of the organized market are achieved in the case of complex and consolidated logistics services. The organized market requires the buyer of the logistics service to adopt a partnership approach with only one LSP (named 4LP provider), who is responsible for the appropriate management of the relations with the LSPs of each service. 2 A PORTFOLIO APPROACH TO CLASSIFY LOGISTICS SERVICES The concept of portfolio analysis was developed at first in finance, aimed at selecting the equity investments assuring the maximization of the investor’s expected payoff at a given level of risk or, correspondingly, the minimization of his risk assuming a given payoff [10]. However, such a concept was proven to have a promising applicability in each field when the allocation of scarce resources is required to maximize a payoff/risk ratio. In particular, portfolio models have been successfully used in two fields namely marketing – e.g. with the BCG matrix [11] and the General Electric matrix [12] – and purchasing, where the portfolio concept is applied at different managerial levels, from the strategic planning to the operational decision making [13]. In the last field, [7] borrows this concept to propose a easy-to-implement model classifying the items to be purchased based two dimensions: (i) the importance of the item, and (ii) the complexity of the supply market. The first dimension concerns the percentage of total purchasing cost, the value that it adds to the product, and the impact on the profitability. The second one deals with the scarcity of suppliers, the entry barriers in the supply market, and other monopolistic conditions, as well as if the buyer can easily replace the product with alternative items. Four categories of items are considered by assuming two values for the two dimensions (i.e. high and low). Each category corresponds to a suitable supply strategy to be pursued, as described next: non critical items, having low importance and low market complexity, should be purchased by exploiting standardization so as to reduce costs and achieve functional efficiency; leverage items, having high market complexity, should be multiple suppliers on the basis paying attention to the effect orders; bottleneck items, with low importance but high market complexity, should be reduced by looking for importance but low typically sourced by of cost/price drivers, of high volumes of substitutes and, if it is not possible, they are to be purchased from carefully selected suppliers assuring the volume and the delivery time desired by the buying firm; strategic items, whose importance and market complexity are both high, have an extensive impact in buyer’s profitability. Therefore they should be managed by enabling long-term collaboration with suppliers so as to assure both availability and fit to specific needs. Several portfolio models extending the Kraljic’s seminal one has been proposed in the literature. [14] classify items on the basis of the level of control (i) on the internal market demand and (ii) on the external supply market, and define the supply situations as plain, internally problematic, externally problematic or complicated. The action plans suitable to each situation are then identified, whose focus is on the purchasing effort, the demand, the supply, and the integration. [15] consider the strategic importance of the purchase and the difficulty of managing the purchasing situation as key dimensions to define the appropriate sourcing strategy, and provide a list of factors influencing both dimensions. Furthermore, they affirm that a methodology to weight the factors is necessary [16], and that each dimension can assume a continuum of values rather than only two ones. According to [17], the Kraljic’s dimensions do not explicitly take into account the relative bargaining power between the buyer and its suppliers. Thus, they include the mutual dependence as key dimension. Similarly, [3] focus on buyer’s and supplier’s specific investments. The attendant scenarios are: market exchange, if both actors do not have to make high investments to exchange the item, strategic partnership in the opposite case, and buyer/supplier captivity, if buyer/supplier’s investments are considerably higher that the ones of the counterpart. The models above present some analogies. All of them include an “internal” dimension, that depends on the use of the item by the buyer (i.e. the item’s importance, the amount of buyer’s specific investments, and other similar variables). The second dimension is related to an “external” variable (e.g. the nature of the supply market, the supplier’s specific investments, and so on). A further analogy refers to a managerial implication: in all models items characterized by high values in both the variables are considered as strategic. Therefore, the sourcing strategy of the strategic items require to be based on partnership relationships, which are characterized by longterm horizon, mutual trust, and high jointly efforts [4]. 2.1 Portfolio matrix of the logistics services A lack in the literature on the portfolio models is that they do not explicitly refer to the services. Moreover, they can not be directly extended to the services because of their different nature: services cannot be stored like physical goods. Thus, specific portfolio model should be developed to address the purchasing of the services. This paper focuses the attention on the logistics services. To our knowledge, only [1] propose a portfolio model of the logistics services classifying them into two categories (i.e. basic and advanced) based on the degree of complexity. The latter is turn depends on several factors, such as: the predominance of managerial or operative activities, the effort required for their customization and re-engineering according to the customer’s needs, and the bundling of sub-services. We propose a portfolio matrix for the logistics services based on two dimensions. The first dimension refers to an internal property of the buyer, namely the strategic importance of the service. It encompasses both economic High of the service Strategic importance 19th International Conference on Production Research Low Leverage Strategic Traditional inventory management Distribution management Warehousing Tracking Material handling Tracing Picking Reverse logistics Non-critical Bottleneck Loading and unloading Routing Packaging SC inventory management Labelling Transportation management Administrative management services Low High Complexity of supply market Figure 1. Portfolio matrix of logistics services. and strategic factors, such as: the weight of the service on the total amount of buyer costs, the potential and actual savings in the logistics, manufacturing and designing costs, the value added included in the buyer’s products, and the premium price that the buyer’s customers are disposed to pay. The second dimension concerns the complexity of the supply market, which takes in several factors referring to the external environment, such as: the novelty and the complexity of the service, the number of potential suppliers and the saturation of their capacity, the uncertainty of the purchasing, and the information asymmetries. Both dimensions can be operationalized as in [15-16; 18-19], which the reader is referred to. Four classes of the logistics services are then defined, namely non-critical, leverage, bottleneck, and strategic. As to sourcing strategies, the non-critical services should be provided focusing on standardization, so as to reduce the transaction costs. The leverage services, whose impact on buyer’s profits is higher, should be procured by exploiting the economies of scale whenever is possible. The bottleneck services should be procured so as to reduce the supply risk, for instance by mechanisms to better involve the provider and share risks with him. Finally, the strategic services can be internalized or outsourced; in this case, they require a partnership relationship with the logistics provider. Figure 1 depicts the classification of the main logistics services into the proposed portfolio matrix. Note that such a classification can appear the same for many industries. Even though this seems to be more strictly true for the complexity of the supply market, also for the strategic importance of the service a similar consideration holds. Thus, the classification of the purchasing of the logistics services is less industry-dependent than the purchasing of physical items. New trends have emerged in the purchasing of the logistics services: the increasing consolidation of logistic services by the LSPs that tend to offer a wider, more complex panel of services; the improvement of internetbased services; and the focus on the core competences both for buying firms – which tend to increase their recourse to outsourcing for the logistics services – and for the logistics providers – which tend to become less assetbased and outsource to low-level logistics operators some not value-added activities, like the material handling and the transportation [1]. Such trends cannot be dealt with the classical portfolio approach and calls for innovative sourcing strategies for the logistics services. 2.2 Weaknesses of the portfolio models The literature on the pitfalls of the portfolio approaches is as wide as the one providing applications of such a technique [20]. The major criticisms refer to their effectiveness both in representing the complexity of business decisions and in providing useful suggestions for practitioners. As to the former aspect, several scholars have pointed out that, by representing the complexity of business decisions by using two basic dimensions, whatever complex or inclusive, two risks emerge. On the one hand, if too simplified dimensions are considered, important variables risk to be neglected [8]. On the other hand, if each dimension is associated with a rich panel of factors, a high managerial effort is required, which cuts down the benefits of the technique [21-22]. Furthermore, some problems arise even for the quantitative tools used to operationalize the dimensions of the model, which are affected by the arbitrary choices of the factors [23], the values assigned to them, and their weights [12]. To avoid this problem, [15] suggest the use of a contingency approach so as to carefully weight the factors influencing both the two dimensions of the model, namely the relative supplier attractiveness and the strength of the relationship between supplier and buyer. However, even in this case a considerable amount of discretionality continues to exist. In respect of the effectiveness of the portfolio approach in suggesting the suitable sourcing strategies, [24] affirms that the portfolio models do not provide the buyer with any pro-active suggestion. In most cases, they give very limited explanation of how to manage each category of items in practice, and reduce their recommendations in suggesting to exploit the contractual power, if it exists, or to prevent risks due to higher supplier contractual strength. Indeed, some empirical evidence show that company implementing portfolio models as proposed in literature tend to focus more on the classification of items than on the development of effective action plans [23]. A further important limitation of the portfolio models influencing their practical usefulness is that they analyze dyadic contexts, namely the supplier-buyer couple, with no matter of the other supplier’s customers or, correspondingly, the other buyer’s suppliers [8]. So doing, they neglect the interdependencies in the SC relations, which however are important to be considered, because the features of the product/service of a supplier are affected by her relationships with each of his customers, and in the same way the needs of the buyer also depends on the features of the other items or services she purchases by several suppliers. Finally, the portfolio models omit any consideration about the development of the product/service, and in particular the relations existing between the engineering, the purchasing, and the supplier types. To avoid this problem, [23] propose a methodology to simultaneously link the items classes, the suppliers types, and the involvement of the actors in defining the items specifications. However, such a methodology seems to be more appropriate for the Table 1. Physical variables Hierarchy Internal market Market Network with 3PL Organized market Number of LSPs Zero Zero Several for each service Several for each service One 4PL and one or more LSPs for each service Number of tiers - - One One or two Two or three Asset intensity of first-tier LSPs - - Asset-based Asset and non asset-based Non asset-based purchasing of tangibles rather than for the logistics services, whose classification is hard to be made. In short, even if the aforementioned portfolio models offer to practitioners some guidelines to manage and design their sourcing strategy, it cannot be considered enough. Thus, the proposed portfolio matrix of the logistics services needs to be integrated so as to overcome the limitations above and better support managers in the design of the appropriate way to manage the sourcing relationships. 3 FORMS OF GOVERNANCE OF LOGISTICS SERVICES In this Section a framework of the forms of governance of the logistics services is proposed, referring to three groups of variables. Such a framework is intended to be a guideline to the managers for the implementation of the proper sourcing relationships of the logistics services. The SC is considered as unit of analysis. It is made up of the buyers of a product, their suppliers, both expressing logistics service demand, and the LSPs. Three dimensions characterizing the SC are considered in the framework, namely the physical, the strategic, and the organizational. Table 1 concerns the physical issues. The first considered variables is horizontal and vertical complexity of the SC [25], namely its physical width and depth [26], which are measured by the number of LSPs and of logistics tiers, respectively. The former measures how many competing firms can provide a given logistics service to the buyers. Its value is zero if there is a vertically integrated firm that internally cares of all logistics functions. The number of tiers indicates if the buyer has a direct interaction with all her logistics providers (number of tiers equals to one) or there are some providers (named firsttier providers) that interact with the buying firms both for the services that they can autonomously provide and for the services that they cannot provide; in this case, they recur to second-tier providers that act as sub-contractors [27-28]. Consequently, first-tier providers can be asset or non-asset based. A comparison among the forms of governance as to strategic dimensions is depicted in Table 2. At first, the decision making process is evaluated as centralized or decentralized. Note that in the organized market, the decision maker about logistics is the 4PL provider, who acts as an intermediary between the customer firm and her logistics providers at an operational level. Interdependence refers to the amount of correlation between the success of the buyer and the policies adopted by her first-tier logistics providers, and vice versa [29-30]. It is evaluated along a scale from low to high and is strictly linked to the commitment in achieving the counterpart’s goals [31]. The sourcing strategy refers only to the procurement of logistics services: although the single sourcing is very uncommon in the logistics field, it is typical of some advanced forms of governance, when buying firms utilize a predominant logistics provider for a large part of the services, but sometimes they recur to one or more others providers to manage the peaks of requirements (second sourcing) [32-33]. The latter is also adopted to reduce the risk of buyer captivity, i.e. the opportunistic behaviour of the provider if she has a high bargaining power [3]. Parallel sourcing is chosen when the buyer purchases a family of the logistics services by more than one provider, each capable to extend his offer to similar services with low switching costs [9]. Lastly, by adopting multiple sourcing, the buying firm is assured to have very low switching costs and a high control of performance, but she renounces to any form of integration with its providers. The definition of service specifications measures the degree of mutual involvement of the logistics service providers and their buyers in designing the service [23]. When the SC is composed by more than an actor, three cases are possible: (i) specifications can be defined exclusively by the buyer, (ii) exclusively by the logistics provider, or (iii) jointly by the buyer and the provider. In the last case, specifications can be mostly quantitative, mostly qualitative or mixed [5]. It is observed that specifications are mostly qualitative if the degree of tacit knowledge they contain is high, namely when they concern organizations having similar culture and attitudes, as it happens between strategic partners. Table 3 synthesizes how the forms of governance differ as to the organizational aspects. Vertical integration, whose value varies from high to low, is evaluated as the extent to Table 2. Strategic variables Hierarchy Internal market Market Network with 3PL Organized market Decision making process Centralized Decentralized Decentralized Decentralized Centralized Interdependence - - Low Medium High Commitment - - Low Medium-high High Sourcing strategy for logistics services - - Multiple sourcing Single or parallel sourcing Single sourcing toward 4PL; single, multiple, or parallel sourcing between 4PL and other logistics providers Definition of service specifications Internally defined Internally defined Exclusively defined by the provider Jointly defined Jointly defined 19th International Conference on Production Research Table 3. Organizational variables Hierarchy Internal market Market Network with 3PL Organized market Vertical integration High High Low Medium Medium-high Time horizon - - Short term Long term Long term between buyer and 4PL provider; medium or long term between 4PL and other logistics providers Bargaining power - - Symmetric Symmetric Asymmetric Level of cooperation - - Low High High Information sharing Medium-high High Low Medium-high High Coordination mechanisms Bureaucratic rules Internal price Market price, short term contracts Long-term contracts Long-term contracts between buyer and 4PL; short or long-term contracts between 4PL and other logistics providers Structural flexibility Low Medium-low High Medium Medium-high which the focal firm owns the stages of the chain [30]. More precisely, it is a measure of the strength of the relationships between firms at different SC stages as well as between who needs the logistics services and who provides them. With respect to the time horizon of the relationships with the service provider short and long term relationships are distinguished. The bargaining power refers to logistics decisions and it is evaluated as asymmetric or symmetric depending on whether or not there is an actor in a predominant position [34]. A range from high to low is adopted to evaluate the level of cooperation, which is a measurement of the commitment of the actors providing the logistics services in pursuing the buyer’s goals, and vice versa [30]. The information sharing refers not only to specific information needed to the provision of the logistics services, but includes also what concerns the strategic objectives of the firms involved in the relationship. If the amount of shared information is high, indeed, the buyer can set her requirements according to the counterpart’s objectives, and correspondingly the logistics provider can define his offer considering the buyer’s in-depth goals. Coordination mechanisms are specific systems that are utilized to actually implement the decisions which are taken [26; 30]. They differ for both the level of formalization and the number of aspects taken into account: in the case of centralized decision making, the bureaucratic rules are usually adequate to assure the implementation; otherwise, firms should agree on an internal price, a market price (by endorsing to simple, short-term contracts), or a more complex set of clauses as defined in a long-term contract [35-36]. Finally, the structural flexibility is evaluated along a continuum ranging from low to high, with possible intermediate values. 3.1 Hierarchy and internal market In a hierarchy, there is a unique actor which makes all decisions, including the ones concerning the definition and the management of logistics services. In a hierarchy the actors acknowledge the authority of the unique decision maker. In practice, pure hierarchies are characterized not only by vertical integration, but also by a bureaucratic approach. The hierarchical archetype does not exclude that participant with no decision making power could generate and suggest alternatives to the central decision maker; however, they cannot exert any veto power on the decisions [37]. In practice, such a form of governance can be effectively adopted only if the decision maker is legitimated to impose his choices to the others actors. To avoid the risk that actors deviate from the central decision maker decisions to pursue their own interests, he can use a suitable systems of rewards and punishments [38-39]. More recently, some deviations to the classical hierarchical form of governance have been proposed. The Internal markets [40] are a form of governance characterized by a hybrid organizational system because the transactions within a firm or among the units of a corporation occur without a centralized top-down control, but are the result of the coordination of the different actors involved. Such form of governance is based on the adoption of market mechanisms called internal prices, which explicitly quantify in terms of money the value connected to each internal exchange. A concept very similar to internal markets is the quasi-market, as proposed by [39]. The adoption of market mechanisms to rule transactions within a hierarchy gives transparency to the behaviour of the actors, whose actions can be explicitly evaluated in term of the effect that they make on the organization as a whole. Therefore, actions are assured be coherent with the organization goals. The main advantages of the internal market, in comparison with a pure hierarchy, are the higher efficiency and the faster responsiveness to the environmental changes. In the field of logistics services, an internal market is defined when the logistics division of a firm uses market mechanisms to allocate logistics resources (e.g. freight assets, inventories, etc.) within the organization. Both hierarchy and internal market should be adopted when the firms decide to internalize the logistics services. As said above, this choice could be pursued for the logistics services so strategic that the firm prefers to make them. 3.2 Pure market At the opposite of the hierarchy, the pure market consists in a form of governance based on the independence between actors, each of them covers no more than a single stage along the chain and makes autonomously decisions aimed at maximizing his own utility rather than the system-wide one. Market transactions are usually spot, and are ruled by an approach known as arm’s length. In other terms, actors aim to maximize their immediate payoffs with no matter of the effect that it causes on the counterpart’s future behaviour. Therefore, this approach does not care about the long-term benefits [2]. Consequently, this approach should be adopted only if the service does not require any mutual involvement of the actors and it can be provided by many logistics providers. The adoption of the pure market seems appropriate only for the logistics services characterized by a low level of the market complexity, namely for the non-critical and the leverage logistics services. 3.3 Networks with 3PL providers At the present, supply relationships are heavily shifting from the arm’s length approach to less greedy strategies, which can assure higher long-term payoffs [6]. The need of more complex strategies has been proven to be stronger when the market complexity of items to be purchased is too high to allow the use of inter-organizational forms of governance based on pure market criteria. Usually, scholars define such cooperative relations as networks. The term refers to different kinds of cooperative inter-organizational relationships [35], having some features in common, such as: (i) a strategic goal shared by the actors, who however maintain to some extent their independence; (ii) the mutual adaptation of culture, organization, goals, and behaviour; (iii) a coordination mechanism that outstrips the strict price mechanism and encompasses long-term aspects; (iv) the existence of legal structures that include some flexibility to deal with the unpredictable environmental contingencies. In the field of logistics, the transition towards cooperative inter-organizational relationships has been pointed out since the Nineties by several researchers, who introduced the concept of third party logistics (3PL). A 3PL is an external firm performing a various panel of logistics functions, otherwise carried out internally [41]. Other scholars have used the terms logistics alliance to indicate “close and long-term relationships between a customer and a provider encompassing the delivery of a wide array of logistics needs” [42]. In such a logistics alliance, partners jointly work in understanding the customer’s logistics needs, developing suitable solutions and measuring performance so as to assure a win-win arrangement [31]. Among the numerous benefits due to the adoption of 3PL [43-44], it is highlighted that, compared with the pure market, 3PL assures more timeliness and customer orientation (e.g. by satisfying asset specifics logistics needs), and prevents actors’ opportunistic behaviour; compared with the hierarchy and internal market, 3PL assures a better responsiveness to the environmental changes and permits the focus on the buyer’s core competencies, turning the fixed in variable costs and reducing financial risks. Therefore, the adoption of 3PL seems proper for the logistics services classified as bottleneck and strategic. Nevertheless, some pitfalls emerge in resorting to 3PL providers [44], due to organizational rather than technological aspects. In fact, although the improvements in ICT tools and infrastructures make information sharing easier than in the past, in most cases actors are still afraid of vulnerability to the knowledge spill-over, thus behavioural and cognitive conservatism emerge [45]. To overcome such problems, two-way feedback systems should be implemented, which formally measure the partner’s performance, and frequent meetings and human resource exchanges should be promoted. However, such mechanisms cannot reduce the strategic inadequacy of the 3PL at the strategic level. Such form of governance proves effective at the operational level, but fails to be effective at the SC strategic level: by adopting logistics partnerships in bounded fields, firms cannot build an holistic vision of their logistics requirements; thus, they are unable to achieve all information needed to make an effective SC reconfiguration [45]. 3.4 Organized market The concept of organized market was introduced by [9] referring to an hybrid organizational system between market and hierarchy aiming at reducing transaction costs in comparison with pure markets, and internal coordination costs in comparison with hierarchical organizations, by means of a specific type of actors. As regards the logistics field, an organized market of logistics services consists in a coordinated system composed by different actors: suppliers, supplier’s suppliers, manufacturers, warehouses, distributors, retailers, as well as logistics providers offering one or more services, their subcontractor (including owners of trucks or other means of transportation). What distinguishes the organized market of the logistics services from other forms of governance is the existence of the fourth party logistics (4PL) provider, which plays a key role: it is the unique firsttier logistics provider and cares of both the strategic and the operational activities [45]. As to the strategic level, it offers its resources, skills and technologies to the customers and designs, builds, and runs comprehensive SC solutions, possibly including all logistics services. At the operational level, it takes care of all customer’s logistics needs, and acts as a mediator between her and the second-tier LSPs by managing all logistics provisions. Some benefits can be achieved by adopting the organized market rather than the network with 3PL providers. Firstly, the 4PL provider focuses on information management as his core competence, so as to reduce the system’s logistics ineffectiveness. This assures a holistic vision of all logistics needs and fosters the customer’s SC reconfiguration as a whole. Secondly, the 4PL provider, even though it does not possess physical assets, offers – via asset-based LSPs – a complex logistics service, by consolidating a wide spectrum of single services, belonging to different classes of the portfolio matrix. In this case, the buying firm is unable to define her purchasing strategy towards the 4PL provider only on the basis of the classification of logistics services as by the portfolio matrix. The 4PL provider, in turn, recurs to the portfolio matrix to manage his relationships with the second-tier LSPs. Thus, the organized market is the best solution in the case of consolidated logistics services made up of services that belong to different classes of the portfolio matrix. 4 CONCLUSIONS This paper has addressed a key topic in the literature, i.e. the sourcing strategies of the logistics services and the organization of the supply chain involving the logistics services providers. In particular, a portfolio model of the logistics services has been proposed, having as key dimensions the strategic importance of the service and the complexity of supply market. It has been used to classify the logistics services as well as to identify the sourcing strategies. The choice of such an approach is due to its ease of understanding; however, several pitfalls of portfolio approaches have been highlighted: their inadequacy in suggesting managers as they should manage the sourcing relationships; the absent consideration of the interdependencies between 19th International Conference on Production Research products/services; and the use of a dyadic rather than a supply chain (SC) point of view. To overcome these limitations, a taxonomy of the forms of governance of the logistics services has been proposed by using three main dimensions, i.e. physical, strategic and organizational. Beside traditional forms of governance (market and hierarchy), three intermediate forms have been identified in the field of logistics services, namely the internal market, the network with 3PL, and the organized market of logistics services. The latter can be considered as an evolution of networks with 3PL, where a LSP – named 4PL provider – gathers all services and acts as mediator between the buyer and the other LSPs. The 4PL provider has a holistic vision of logistics needs of her customer so as to favour a more knowledgeable SC reconfiguration. The forms of governance suitable to the different classes of the logistics services are suggested. In particular, hierarchy and internal market should be adopted when the firms decide to internalize the logistics services. The adoption of the pure market seems appropriate for the logistics services characterized by a low level of the market complexity. The adoption of the network with 3PL seems proper for the logistics services classified as bottleneck and strategic. Finally, the organized market is appears to be suitable for the complex and consolidated logistics services. Further research will be devoted to test these propositions. In particular, mechanisms to implement the organized market of the logistics services will be investigated, by paying attention to the kind of relationships and the coordination mechanisms among the actors at the different SC interfaces. 5 REFERENCES [1] Andersson D., Norrman A., 2002. Procurement of logistics services – a minutes work or a multi-year project, European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 8, 3-14. [2] Simchi-Levi D., Kaminsky P., Simchi-Levi E., 2000. Designing and managing the supply chain: concepts, strategies and case studies, McGraw-Hill International, Singapore. [3] Bensaou, B.M., 1999. Portfolios of buyer–supplier relationships. Sloan Management Review Summer, 35-44. [4] Gadde L.E., Snehoda I., 2000. Making the most of supplier relationships, Industrial Marketing Management 29, 305-316. [5] Nellore R., Söderquist K., 2000. Strategic outsourcing through specifications, Omega 28, 525-540. [6] Skjoett-Larsen T., 2000. Third party logistics – from an interorganizational point of view, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 30 (2), 112-127. [7] Kraljic P., 1983. Purchasing must become supply management. Harvard Business Review, SeptemberOctober, 109-117. [8] Dubois A., Pedersen A.C., 2002. Why Relationships do not Fit into Purchasing Portfolio Models – A Comparison Between the Portfolio and Industrial Network Approaches, European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 8 (1), 35-42. [9] Colombo M.G., Mariotti S., 1998. Organizing Vertical Markets: the Italtel Case, European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 4, 7-19. [10] Markowitz H., 1952. Portfolio selection. Journal of Finance 7 (3), 77-91 [11] Porter M., 1980. Competitive Strategy, The Free Press, New York. [12] Day G.S., 1986. Analysis for Strategic Market Decisions, West Publishing, St. Paul, MN, USA. [13] Turnbull, P.W., 1990. A review of portfolio planning models for industrial marketing and purchasing management. European Journal of Marketing 24(3), 7-22. [14] Van Stekelenborg R.H.A., Kornelius L., 1994. A diversified approach towards purchasing and supply. IFIP Transactions. B, Applications in Technology, 4555. [15] Olsen R.F., Ellram L.M., 1997. A portfolio approach to supplier relationships, Industrial Marketing Management 26 (2), 101–113. [16] Narasimhan R., 1983. An Analytical Approach to Supplier Selection, Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management 19, 27-32. [17] Gelderman C.J., van Weele A.J., 2000, New perspectives on Kraljic’s purchasing portfolio approach, Proceedings from the Nineth International Annual IPSERA Conference, London, Canada, 291– 298. [18] Thompson K., 1991. Scaling Evaluative Criteria and Supplier Performance Estimates in Weighted Point Prepurchase Decision Models. International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management 27, 27-36 [19] Min H., 1994. International Supplier Selection: A MultiAttribute Utility Approach. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 24, 2433. [20] Gelderman C.J., van Weele A.J., 2005. Purchasing portfolio usage and purchasing sophistication, working paper. [21] Haspelagh P., 1982. Portfolio Planning: Uses and Limits. Harvard Business Review 60 (1), 58-73. [22] Gelderman C.J., van Weele A.J., 2003. Handling measurement issues and strategic directions in Kraljic’s purchasing portfolio model, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 9(5-6), 207-216. [23] Nellore R., Söderquist K., 2000. Portfolio approaches to procurement - Analysing the missing link to specifications”, Long Range Planning 33(2), 245-267. [24] Cox A., 1997. Business success – A way of thinking about strategy, critical supply chain assets and operational best practice, Earlsgate Press, Peterborough, UK. [25] Choi T.Y., Hong Y., 2002. Unveiling the structure of supply networks: case studies in Honda, Acura and Daimler Chrysler, Journal of Operations Management 20, 469-493. [26] Carbonara N. Giannoccaro I. Pontrandolfo P., 2002. Supply chains within industrial districts: a theoretical framework, International Journal of Production Economics 76, 159-176. [27] Lamming R., 1993. Beyond partnership: strategies for innovation and lean supply, Prentice Hall International, Hemel Hempstead, UK. [28] Nishiguchi T., 1994. Strategic industrial clustering, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, USA. [29] Johnson L., 1999. Strategic integration in industrial distribution channels: managing the interfirm relationship as a strategic asset, Journal of the Academy in Marketing Science 27(1), 4-18. [30] Stock G.N., Greis N.P., Kasarda J.D., 2000. Enterprise logistics and supply chain structure: the [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] role of fit, Journal of Operations Management 18, 531547. Bowersox D.J., 1990. Strategic benefits of logistics alliances, Harvard Business Review 68, July-August, 36-45. Riordan M.H., Sappington D.E.M., 1989. Second sourcing, Rand Journal of Economics 20, 41-58. Choi J.P., Davidson C., 2004. Strategic Second Sourcing by Multinationals, International Economic Review 45 (2), 579-600. Giannoccaro I., Pontrandolfo P., 2003. The organizational perspective in supply chain management: an empirical analysis in Southern Italy, International Journal of Logistics: Research and Applications 6(3), 107-123. Nassimbeni G., 1998. Network structures and coordination mechanisms, International Journal of Operation and Production Management 18(6), 538547. Xu L., Beamon B.M., 2006. Supply chain coordination and cooperation mechanisms: an attribute-based approach, The Journal of Supply Chain Management 42 (1), 4-12. Siggelkov N., Rivkin J.W., 2005. Speed and search: designing organizations for turbulence and complexity, Organization Science 16 (2), 101-122. Williamson O.E., 1975. Market and hierarchies: analysis and antitrust implications, Free Press, New York, NY, USA. [39] Barney J.B., Ouchi W.G., 1984. Information cost and organizational governance, mimeo. Italian translation: Costi delle informazioni e strutture economiche delle transazioni. In : Nacamulli, R.C.D., Rugiadini, A. (Eds.) (1985), Organizzazione e mercato, Il Mulino, Bologna, Italy. [40] Malone T.W., 2004. Bringing the market inside, Harvard Business Review 82, April, 106-114. [41] Lieb R.C., Millen R.A., van Wassenhove L., 1993, Third-party logistics services: a comparison of experienced American and European manufacturers, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 23 (6), 35-44. [42] Bagchi P., Virum H., 1996. European logistics alliances: a management model, International Journal of Logistics Management, 7 (1), 93-108. [43] Leahy S.E., Murphy P.R., Poist R.F., 1995. Determinants of successful logistical relationships: a third-party provider perspective, Transportation Journal 35 (2), 5-13. [44] Razzaque M.A., Sheng C.C., 1998. Outsourcing of logistics functions: a literature survey, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 28 (2), 89-107. [45] Visser E.J., Konrad K., Salden R., 2006. Developing 4th party services: empirical evidence on the relevance of dynamic transaction-cost theory for analysing logistic system innovation, working paper.