summary of argument - Harvard Law School

advertisement

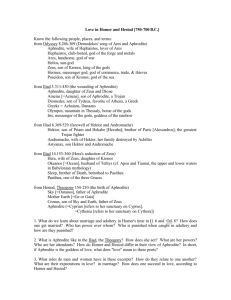

STATEMENT OF THE CASE Aphrodite Cosmetics, Inc. (“Aphrodite”) is one of the leading cosmetics and skincare companies in the United States. It currently produces more than twenty different lines of products, (R.2), which it sells primarily through boutiques and department stores. (R.3) Aphrodite earned more than six billion dollars of total revenue during fiscal year 2005. (R.2) Internet sales account for approximately 0.7% of this total revenue. (R.2, 3) Since 1980, Aphrodite has dedicated between one-quarter and one-third of its annual budget to advertising its products—including a successful and highly publicized “Be Beautiful” campaign. (R.3) Adam’s Apple Markets, Inc. (“Adam’s Apple”) is an organic and natural foods supermarket chain with 183 locations nationwide. (R.2) In addition to food items, Adam’s Apple exclusively distributes Soleil Skincare Products (“Soleil”), a brand of “cruelty-free” cosmetics and skincare products. (R.2) Revenue from Soleil products account for approximately ten percent of Adam’s Apple’s gross sales, which totaled approximately $380 million in fiscal year 2005. (R.2) From 1999 to 2000, Adam’s Apple’s sales of Soleil increased by twenty-two percent. (R.3) However, from 2002 to 2005, sales decreased by twenty percent. (R.6) During the late 1990s, various media sources and corporate watchdogs reported that Aphrodite tested their products on animals. (R.3, 9–10) Sales of Aphrodite products declined fourteen percent between 1999 and 2000. (R.3) In September 2002, Aphrodite ceased conducting animal testing in its own laboratory and established the cosmetics industry’s first code of conduct. (R.4) Recognizing its role as “a leader in the cosmetics industry” (R.13), Aphrodite provided general facts about animal testing in the cosmetics 1 industry (R.11), and indicated its belief that “animals deserve respect and dignity” (R.12) and that “cosmetics testing on animals is unethical and unnecessary.” (R.11) It stated that it would “not test [its] products on animals” and further intended to “promote animal protection throughout [its] business activities.” (R.11) In addition to displaying the code of conduct on its website and in its corporate literature (R.4), Aphrodite issued a series of public statements regarding its stance on animal testing. These included a September 16, 2002 press release (R.12), a December 14, 2002 letter to the editor of The Amesville Chronicle (R.13), a February 2003 document entitled “The Aphrodite Code of Conduct: What it is, How it Works” (R.4), a March 2003 “Production Primer,” (R.5) and an October 1, 2005 letter to The New York Times. (R.5) Aphrodite’s public statements did not reference other cosmetics manufacturers or their products. (R.4–5, 11–13) In October 2004, prominent news outlets, including CBS News, Financial Times, The New York Times, and The Amesville Chronicle, began reporting that the suppliers of Aphrodite’s ingredients continued to test their products on animals. (R.6–8) In January 2006, Adam’s Apple brought suit against Aphrodite under the Lanham Act and the Ames False Advertising Statute. (R.6) Adam’s Apple charged that Aphrodite had made misleading representations of fact, including that it was “morally opposed to animal testing,” that it “will not engage in abusive or inhumane treatment of animals,” and that it is an industry leader on the issue of animal testing. (R.6). Adam’s Apple claimed loss of sales, potential sales, and goodwill resulting from Aphrodite’s conduct. (R.6–7) Aphrodite moved to dismiss the Lanham Act claim under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6), stating that the plaintiffs had not satisfied prudential standing and that the speech 2 concerned was not “commercial.” (R.15) The District Court of Ames found that the plaintiffs had prudential standing but granted Aphrodite’s motion on the grounds that the speech was not commercial. (R.16) The Ames Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the District Court’s ruling on commercial speech but held that Adam’s Apple lacked prudential standing to sue. (R.25–26) This Court granted certiorari to review the rulings on prudential standing and commercial speech. (R.27) SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT Adam’s Apple has failed to meet its burden of establishing prudential standing because the harm it alleges is not the type of injury the Lanham Act sought to redress and because other parties are better suited to vindicate the public interest. Granting standing to Adam’s Apple would upset judicially-imposed prudential restrictions limiting standing to those parties in the best position to effectuate the Act’s purpose. The Lanham Act protects marketplace competition. In section 43(a), Congress confined relief to those parties injured by anti-competitive conduct. Parties in close competition who could allege a competitive injury, therefore, have “reasonable interests” to assert a Lanham Act claim. The circuits have developed two tests for prudential standing under the Lanham Act. In this case, both tests lead to the conclusion that Adam’s Apple fails to establish prudential standing because it has not sustained a competitive injury. Competition between Adam’s Apple and Aphrodite is minimal at best, and Adam’s Apple has not demonstrated that its loss in sales was closely linked to Aphrodite’s general statements. Furthermore, granting Adam’s Apple standing would create a risk of duplicative 3 litigation and conflicts of interest for future claimants, thereby subverting the purpose of the Lanham Act by transforming it into a competitive tool. Finally, because other parties are better suited to vindicate the public interest, this Court should affirm the decision of the Ames Circuit Court of Appeals and deny standing on prudential grounds. This Court should likewise affirm the Ames Circuit Court’s decision not to label Aphrodite’s statements about animal testing as commercial speech because doing so would chill valuable speech without significantly protecting consumers. In its various manifestations, the commercial speech doctrine has targeted speech that proposes a commercial transaction. This Court has avoided expansive tests, like Petitioner’s, that would treat a company’s comments on public issues in a similar fashion to labels on its products. The balancing test adopted in Bolger v. Youngs Drug Products Corporation successfully allows the Court to distinguish representations that do not afford the opportunity for counter-speech from those that allow for public scrutiny and debate. In this case, Petitioner asks the Court to radically expand the commercial speech category. Unlike true commercial speech, Aphrodite’s participation in the public debate over animal testing is unlikely to produce an immediate negative impact. Instead, labeling Aphrodite’s speech commercial, especially under a broad test such as Petitioner’s, will result in the suppression of speech traditionally considered noncommercial. Even if this Court would characterize particular statements made by Aphrodite as commercial, any commercial elements are inextricably intertwined with non-commercial speech. Treating the whole as commercial will chill protected speech. Lastly, it will allow companies to use the Lanham Act as a tool of unfair competition rather than as a defense against it. 4 For these reasons, the Court should affirm the decision of the Ames Circuit. I. ADAM’S APPLE CANNOT ESTABLISH PRUDENTIAL STANDING BECAUSE ITS ALLEGED HARM IS NOT THE TYPE OF INJURY THE LANHAM ACT SOUGHT TO REDRESS AND BECAUSE IT IS NOT THE BEST PARTY TO VINDICATE THE PUBLIC INTEREST. “[T]he question of standing is whether the litigant is entitled to have the court decide the merits of the dispute or of particular issues.” Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 498 (1975). Article III of the Constitution requires a plaintiff to present a “case or controversy” between herself and the defendant as a prerequisite for bringing suit, often by establishing an injury in fact. Elk Grove Unified Sch. Dist. v. Newdow, 542 U.S. 1, 12 (2004). Beyond this threshold constitutional issue, the Court has imposed “prudential” limits on the class of persons who may invoke the decisional and remedial powers of federal courts. Warth, 422 U.S. at 500. Prudential standing plays an integral role in judicial self-government, Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560 (1992), by allowing the judiciary “to avoid deciding questions of broad social import where no individual rights would be vindicated and to limit access to the federal courts to those litigants best suited to assert a particular claim,” Gladstone Realtors v. Vill. of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 99–100 (1979). While the prudential standing inquiry is separate from constitutional standing, it “must be answered by reference to the Art. III notion that federal courts may exercise power only in the last resort, and as a necessity.” Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737, 752 (1984) (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). 5 Both the constitutional and prudential standing inquiries require a complainant “clearly to allege facts demonstrating that he is a proper party to invoke judicial resolution of the dispute and the exercise of the court’s remedial powers.” Warth, 422 U.S. at 518. While Article III standing is a “threshold question in every federal case,” id. at 498, Congress may abrogate prudential standing limitations, thereby allowing a plaintiff to establish standing under Article III alone, id. at 501. However, the “prudential standing doctrine . . . applies unless it is expressly negated.” Bennett v. Spear, 520 U.S. 154, 163 (1997). Courts have consistently held that Congress did not expressly negate the prudential standing inquiry when passing the Lanham Act. See, e.g., Conte Bros. Auto., Inc. v. Quaker State-Slick 50, Inc., 165 F.3d 221, 230 (3d Cir. 1998); Procter & Gamble Co. v. Amway Corp., 242 F.3d 539, 562 (5th Cir. 2001). Because Congress has not abrogated prudential standing under the Lanham Act, the Petitioner maintains the burden of demonstrating prudential standing.1 For a statute-based claim, the application of prudential standing narrows the body of plaintiffs to those who will best effectuate the statute’s purpose. Under section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, the “dispositive question” of prudential standing is whether the plaintiff “has a reasonable interest to be protected against false advertising.” Waits v. Frito-Lay, Inc., 978 F.2d 1093, 1108 (9th Cir. 1992) (internal citations and quotation marks omitted); Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 230. The circuits have derived two tests to determine whether a plaintiff possesses a “reasonable interest.” Adam’s Apple fails to satisfy prudential standing under either test because the harm it alleges is not the type Congress and the courts have intended the Lanham Act to redress and because other parties are better suited to vindicate the public interest. 1 No court has recognized a presumption of prudential standing under the Lanham Act. 6 A. Congress Limited the Lanham Act for the Purpose of Redressing Competitive Injuries. The Lanham Act was not intended to address all acts of false advertising. When Congress first passed the Act in 1946, it contained no reference to commercial advertising. Section 43(a)(1) of the Act prohibited competitors from “affix[ing] . . . a false designation” to their goods, ch. 540, § 43, 60 Stat. 427 (1946) (current version at 15 U.S.C. § 1125), which courts interpreted as preventing producers or individuals from “passing off” their wares as those of a rival. See, e.g., Samson Crane Co. v. Union Nat’l Sales, 87 F. Supp. 218, 222 (D. Mass. 1949). Thus, in its inaugural form, the text of section 43(a)(1) primarily protected parties against the misuse of their trademarks. See Lillian R. BeVier, Competitor Suits for False Advertising Under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act: A Puzzle in the Law of Deception, 78 Va. L. Rev. 1, 22 (1992) (“Congress appears to have been thinking almost exclusively in trademark terms when it considered the bill.”). Over time, courts have expanded their interpretation of the Lanham Act to include false advertisements as well as trademark violations. In codifying this additional cause of action in its 1988 amendments, however, Congress expressed its intent to limit the Act’s protection to commercial parties harmed by unfair competitive practices. 15 U.S.C. § 1127 (2000). Thus, when a Lanham Act claim solely concerns false advertising and not the misuse of another company’s trademark, “it is actionable under section 43(a) only insofar as the Lanham Act’s other purpose of preventing ‘unfair competition’ is served.” 7 Waits, 978 F.2d at 1109 (citing U-Haul Int’l, Inc. v. Jartran, Inc., 681 F.2d 1159, 1162 (9th Cir. 1982)). 2 The Petitioner states that a defendant may be liable to “any person who believes that he or she is or is likely to be damaged.” (Petr.’s Br. 11) (citing 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(B) (2000)). However, the drafters never intended the Act to be so broadly construed. Instead, the Act was meant to fill the “gap in federal unfair competition law,” S.Rep. No. 100–515, 100th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in 1988 U.S.C.C.A.N. 5577, 5603 (May 12, 1988), left after this Court’s decision in Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins striking down the use of general federal law. 304 U.S. 64 (1938). Courts, recognizing Congressional intent, have limited the Act’s application to parties in close competition. “Conferring standing to the full extent implied by the text of § 43(a) would give standing to parties, such as consumers, having no competitive or commercial interests affected by the conduct at issue.” Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 229. Because the 1988 amendments simply codified the courts’ jurisprudence, S.Rep. No. 100–515, 1988 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 5603, it is unlikely that the drafters intended to imply the broad judicial construction advocated by Petitioner. In accordance with the purpose of the Lanham Act, Congress and the courts have reserved causes of action concerning commercial advertising to commercial plaintiffs alleging actions of unfair competition.3 The Ninth Circuit has noted that limiting Lanham 2 The claim brought by Adam’s Apple involves general company statements rather than use of a trademark owned by Adam’s Apple or Soleil. Therefore, Adam’s Apple lacks standing for a false endorsement claim under 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(1)(A) (2000). Similarly, Adam’s Apple lacks standing to claim loss of goodwill for harm related to the basic integrity of Soleil’s products. See infra (I)(C)(2)(b). 3 The limited scope of the Lanham Act differs from other remedial statutes, such as the Clayton Act, in which Congress created a private enforcement mechanism. Blue Shield of Va. v. McCready, 457 U.S. 465, 472 (1982) (the Clayton Act “does not confine its protection to consumers, or to purchasers, or to 8 Act prudential standing to competitors serves the purpose of preventing unfair competition through advertising: If Section 43(a) is not confined to injury to a competitor in the case of a false designation, it becomes a federal statute creating the tort of misrepresentation, actionable as to any goods or services in commerce affected by the misrepresentation. . . . Broadening the Act from unfair competition to unfair trade ‘is equivalent’ to the complete dilution of the concept of unfair competition. Halicki v. United Artists Commc’ns, Inc., 812 F.2d 1213, 1214 (9th Cir. 1987) (citing Callmann, Unfair Competition, Trademarks and Monopolies § 209 (1981 ed., 1986 supp.)). The Ninth Circuit’s emphasis on competitive parties reflects Congress’s intentions. Furthermore, neither the stated intent of the Act nor its legislative history expresses Congressional intent to protect commercial retailers or distributors. See S.Rep., 1988 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 5580 (noting that the Lanham Act protections are “important to both consumers and producers”). Protecting parties against unfair competition in accordance with the purpose and intent of the Lanham Act requires courts to redress competitive injuries. Therefore, parties seeking prudential standing under the Act must allege an injury “harmful to the plaintiff’s ability to compete with the defendant.” Barrus v. Sylvania, 55 F.3d 468, 470 (9th Cir. 1995) (citing Halicki, 812 F.2d at 1214). B. The Existing Tests for Prudential Standing Require the Plaintiff To Demonstrate a Competitive Injury. 1. The Circuit Courts Have Developed Two Tests for Prudential Standing Under the Lanham Act. competitors, or to sellers. . . . The Act is comprehensive in its terms and coverage, protecting all who are made victims of the forbidden practices by whomever they may be perpetrated.”) (citations omitted). 9 The circuits have articulated two tests for prudential standing based on the purpose of the Lanham Act. Under either test, the plaintiff retains the burden “to allege facts demonstrating that he is a proper party to invoke judicial resolution of the dispute and the exercise of the court’s remedial powers.” Warth, 422 U.S. at 518. The first test, set forth by the Ninth Circuit, requires a claimant for false advertisement under the Lanham Act to (1) be a competitor of the defendant and (2) allege a competitive injury. Waits, 978 F.2d at 1109. This test requires a competitor to allege a sufficient link between the defendant’s alleged false advertising and an injury harmful to the plaintiff’s ability to compete. The Ames, Second, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits have also adopted this test. Adam’s Apple Markets, Inc. v. Aphrodite Cosmetics, Inc., Civ. No. 06-705, slip. op. at R.25–26 (Ames Cir. 2006); Telecom Int’l. Am., Ltd. v. AT&T Corp., 280 F.3d 175, 197 (2d Cir. 2001); L.S. Heath & Son, Inc. v. AT&T Info. Sys., Inc., 9 F.3d 561, 575 (7th Cir. 1993); Stanfield v. Osborne Indus., Inc., 52 F.3d 867, 873 (10th Cir. 1995). For clarity, we will refer to this as the “competitive injury test.” Alternatively, the Third Circuit has adopted a multi-factor test derived from this Court’s antitrust standing doctrine in Associated General Contractors of California, Inc. v. California State Council of Carpenters, 459 U.S. 519, 538–44 (1983).4 This test considers: (1) the nature of the plaintiff’s alleged injury; (2) the directness of the asserted injury; (3) the proximity of the party to the alleged injurious conduct; (4) the speculativeness of the damages claim; and (5) the risk of duplicative damages. Conte The Petitioner uses a substantially similar test that is also based on this Court’s antitrust standing doctrine. (Petr.’s Br. 14) (citing McCready, 457 U.S. at 473). However, since the Court decided Associated General after McCready and delineated a standard that was subsequently applied by Circuit courts to determine prudential standing under the Lanham Act, the Associated General test provides more guidance. 4 10 Bros., 165 F.3d at 233 (internal citations omitted). The Fifth Circuit and at least one district court in the Eleventh Circuit have followed this “less categorical multi-factor test.” Phoenix of Broward, Inc. v. McDonald’s Corp., 441 F. Supp. 2d 1241, 1249 (N.D. Ga. 2006); see Procter & Gamble, 242 F.3d at 562–63. For clarity, we will refer to this as the “multi-factor test.” 2. Courts Have Applied the Two Tests With a Common Emphasis on Competitive Injury. Both the multi-factor and competitive injury tests for prudential standing focus on whether a competitive injury exists, in accordance with the Lanham Act’s aim of preventing unfair competition. See L.S. Heath & Son, 9 F.3d at 575 (“In order to have standing to allege a false advertising claim . . . the plaintiff must assert a discernible competitive injury.”); Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 234 (“the focus of the Lanham Act is on ‘commercial interests [that] have been harmed by a competitor’s false advertising.’” (quoting Granite State Ins. Co. v. Aamco Transmissions, Inc., 57 F.3d 316, 321 (3d Cir. 1995))). Indeed, one Fifth Circuit judge has described the multi-factor test in the following way: “Although technically distinct, these five factors can be distilled into an essential inquiry . . . whether, in light of the competitive relationship between the parties, there is a sufficiently direct link between the asserted injury and the alleged false advertising.” Ford v. NYLcare Health Plans of Gulf Coast, Inc., 301 F.3d 329, 337 (5th Cir. 2002) (Benavides, J., concurring) (denying Lanham Act standing to physicians where HMOs falsely advertised improved quality of care resulting from their management techniques). 11 Several district courts applying the multi-factor test have found a lack of direct competition to be determinative. See Alphamed Pharms. Corp. v. Arriva Pharms., Inc., 391 F. Supp. 2d 1148, 1162–64 (S.D. Fla. 2005) (denying standing under the multi-factor test based on the lack of competition between two pharmaceutical manufacturers and their relevant products); see also Nevyas v. Morgan, 309 F. Supp. 2d. 673, 680 (E.D. Pa. 2004) (denying standing under the multi-factor test because a disenchanted former patient and a doctor were not commercial competitors). Moreover, at least one court has been reluctant to grant standing to a non-competitor under the multi-factor test even when various factors weigh in favor of standing. See MCW, Inc. v. BadBusinessBureau.com, L.L.C., No. Civ.A.3:02-CV-2727-G, 2004 WL 833595, at *14 (N.D. Tex. April 19, 2004) (denying standing to a non-competitor although no other party was more proximate to the alleged harm and the damages were neither speculative nor duplicative). In fact, no case cited by the Petitioner grants standing to a non-competitor plaintiff under the Lanham Act utilizing the competitive injury, multi-factor, or McCready tests. Courts within the Eighth Circuit have applied both tests because of their essentially similar functions. Renaissance Leasing, L.L.C. v. Vermeer Mfg. Co., No. 05445-CV-W-FJG, 2006 WL 1447032, at *3 (W.D. Mo. May 23, 2006) (citing Am. Ass’n of Orthodontists v. Yellow Book, 434 F.3d 1100, 1103–04 (8th Cir. 2006)) (remarking on the Eighth Circuit’s demurral to choose between the two tests). Utilizing both the multifactor and competitive injury tests, the district court in Renaissance Leasing denied Lanham Act standing to a retailer attempting to sue a manufacturer, stating “it is obvious that the plaintiffs are not competitors.” 2006 WL 1447032, at *5, *7. 12 The courts’ common emphasis on competitive injury, as elaborated through these two tests, provides ample tools to examine prudential standing in this and future cases. Lower courts have consistently denied suits similar to the case at bar for lack of competition and competitive harm. This Court would serve the purposes of the Lanham Act by upholding this precedent. C. Adam’s Apple Lacks Prudential Standing Under Either Test Because Aphrodite’s Policy Statements Did Not Cause a Competitive Injury and Because Other Parties Are Better Suited To Vindicate the Public Interest. Both tests’ focus on a competitive injury should direct this Court to the conclusion that Adam’s Apple does not have standing. Adam’s Apple is not a competitor of Aphrodite in any meaningful sense and does not allege a competitive injury that falls within the scope of the Lanham Act. Therefore, it should seek to vindicate its claims in other fora. 1. Adam’s Apple Lacks Prudential Standing Under the Competitive Injury Test. To establish standing for a Lanham Act claim under the competitive injury test, a plaintiff must show “(1) a commercial injury based upon a misrepresentation about a product; and (2) that the injury is ‘competitive,’ or harmful to the plaintiff’s ability to compete with the defendant.” Jack Russell Terrier Network of N. Cal. v. Am. Kennel Club, Inc., 407 F.3d 1027, 1037 (9th Cir. 2005) (citing Halicki, 812 F.2d at 1214); see also Waits, 978 F.2d at 1109. A plaintiff must thus demonstrate both that it competes with the defendant and that the defendant’s product misrepresentation has caused a competitive injury. 13 Aphrodite and Adam’s Apple are not “competitors” within the meaning of the Lanham Act because they have fundamentally different supply-chain roles in the market for cosmetics and skincare products. Aphrodite is a major manufacturer of cosmetic products sold primarily in boutiques and department stores, while Adam’s Apple is a supermarket chain that sells but does not manufacture cosmetics and skincare products. (R.2, 3) In contrast, Aphrodite directly competes against other manufacturers such as Soleil. These manufacturers are the entities most affected by Aphrodite’s advertising and business practices. While Petitioner argues that Aphrodite also competes with Adam’s Apple through the internet, (Petr.’s Br. 23–24), these transactions comprise only 0.7% of Aphrodite’s annual sales, (R.2, 3). In discussing its denial of standing to a retailer suing a manufacturer, the Third Circuit explained, “[o]ur conclusion would not be altered even if we were to assume some percentage of [the product’s] sales were made directly to end users and that the parties, therefore, were ‘competitors’ in some limited sense.” Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 235. Even if Adam’s Apple is a competitor “in some limited sense,” this tenuous relationship does not give rise to the unfair competition that the Lanham Act sought to redress. In addition, Adam’s Apple failed to establish a direct link between the alleged harm and Aphrodite’s policy statements. Aphrodite’s statements regarding its animal testing policy did not reference the products of Adam’s Apple, Soleil, or any other companies. (R.4–5, 11–13) Without this direct link, other theories are as likely to explain the downturn in Soleil sales since 2002. For example, the decline comes after the twentytwo percent rise between 1999 and 2000, (R.3), and therefore could reflect a market return to Soleil’s baseline sales levels. Additionally, exogenous factors such as a change 14 in consumer preferences could have contributed to the decline in Soleil sales. The plaintiff’s allegations compare Soleil sales to Aphrodite sales in an attenuated causal chain, ignoring these and other variables. Furthermore, Adam’s Apple would likely face great difficulty in developing studies that disaggregate consumer purchases of cosmetics from the remaining ninety percent of its gross sales. Compare Joint Stock Soc’y v. UDV N. Am., Inc., 266 F.3d 164, 182 (3d Cir. 2001) (surveys produced “could support a finding that the defendants have misled consumers regarding the origin and nature of their products.”) with Ortho Pharm. Corp. v. Cosprophar, Inc., 32 F.3d 690, 695 (2d Cir. 1994) (denying standing where plaintiff had not produced consumer surveys or witnesses to confirm that cosmetics would be substituted for drugs because parties were not in obvious competition). Because Adam’s Apple is not in competition with Aphrodite and cannot show a direct link between the alleged harm and Aphrodite’s statements, it fails to establish prudential standing under the competitive injury test. 2. Adam’s Apple Also Fails to Meet the Requirements of Prudential Standing Under the Multi-Factor Test. Under the multi-factor test, courts consider: (1) the nature of the plaintiff’s alleged injury; (2) the directness of the asserted injury; (3) the proximity of the party to the alleged injurious conduct; (4) the speculativeness of the damages; and (5) the risk of duplicative damages. Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 233 (citation omitted) (denying standing to retail sellers of engine lubricant bringing a Lanham Act claim against a lubricant manufacturer). In the case at bar, each factor weighs against standing. 15 a. The First Factor Weighs Against Standing Because the Alleged Injury Is Not the Type Congress Sought To Redress. In evaluating the nature of the plaintiff’s alleged injury, courts ask whether the injury is “of a type that Congress sought to redress in providing a private remedy” for violations of the Lanham Act. Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 233 (quoting Associated Gen., 459 U.S. at 538). As shown above, the Lanham Act is intended to redress competitive injuries. See supra I(A). In this case, Adam’s Apple has not alleged harm from a competitor’s false advertising because a grocery store and a cosmetics manufacturer are not market competitors. See supra I(C)(1). In the case closest to the one at bar, the Third Circuit determined that the first factor militated against granting a distributor standing to sue a manufacturer. Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 234 (quoting Associated Gen., 459 U.S. at 538) (“The type of injury suffered by Appellants—loss of sales at the retail level because of alleged false advertising [by a manufacturer]—does not impact the Appellants’ ability to compete . . . . Therefore, the alleged harm is not of the ‘type that Congress sought to redress’ by enacting the Lanham Act.”); cf. Procter & Gamble, 242 F.3d at 563 (denying Lanham Act standing because reduced sales resulting from rumors of defendant’s satanic worship was not the type of injury Congress sought to redress). Because Adam’s Apple cannot show that it has suffered commercial harm from a competitor’s false advertising, the alleged harm is not the type Congress sought to redress through the Lanham Act. Therefore, the first factor weighs against standing. b. The Second Factor Weighs Against Standing Because Aphrodite’s Policy Statements Did Not Target Adam’s Apple. 16 In analyzing the second factor, courts have examined the “character of the relationship between the alleged [Lanham Act] violation and the [plaintiff’s] alleged injury.” Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 234 (citing Associated Gen., 459 U.S. at 545). The second factor weighs against standing if this relationship is “tenuous and speculative” in nature. Id. Adam’s Apple claims that Aphrodite’s allegedly false statements caused it to suffer a loss of sales, potential sales, and goodwill. (R.6–7) However, the Third Circuit rejected a similar attempt to connect an alleged injury to a defendant’s statement that did not explicitly target the plaintiff or its products. Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 234 (noting that the defendants did not “falsely represent[] the characteristics of products marketed by the plaintiffs,” and that “plaintiffs do not allege that defendants ran advertisements that said ‘don’t buy engine additive at Conte Brothers . . . instead, buy Slick 50 directly from the manufacturer’”). Similarly, Aphrodite’s press statements and Code of Conduct did not mention any manufacturers, much less Adam’s Apple. Without such targeting, the relationship between Aphrodite’s statements and Adam’s Apple’s alleged injuries are tenuous at best. The Petitioner argues that targeting is unnecessary because the First and Second Circuits have granted standing to plaintiffs with far more tenuous relationships. (Petr.’s Br. 16–17) However, the courts justified these claims by referencing the potential for industry-wide harm, which is not present in this case. See Camel Hair & Cashmere Inst. of Am., Inc. v. Associated Dry Goods Corp., 799 F.2d 6, 12 (1st Cir. 1986) (granting prudential standing where defendants’ sale of coats labeled as fifty percent cashmere but containing only twelve percent cashmere risked damaging “cashmere’s reputation as a 17 high quality fibre”); cf. PPX Enters., Inc. v. Audiofidelity, Inc., 746 F.2d 120, 125 (2d Cir. 1984) (granting prudential standing to “genuine business competitors” where sales of “Jimi Hendrix” recordings in which Hendrix only played back-up guitar would make consumers “reluctant to buy other Hendrix recordings, including those in which plaintiffs have their interests”). For analogous harm to be inflicted on Adam’s Apple, consumers would have to stop buying cruelty-free products altogether due to a loss of confidence in the “no animal testing” market. Adam’s Apple, however, complains that consumers simply purchased from a different manufacturer than Soleil, rather than foregoing cruelty-free products as a whole. (R.6) (“consumers who oppose animal testing have been misled into buying Aphrodite products”). Thus, the second factor also weighs against standing. c. The Third Factor Weighs Against Standing Because Other Parties Are Better Situated To Vindicate the Public Interest. The third factor requires a court to determine whether there is “an identifiable class of persons whose self-interest would normally motivate them to vindicate the public interest.” Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 234 (citing Associated Gen., 459 U.S. at 542). The existence of such a class “diminishes the justification for allowing a more remote party . . . to perform the office of a private attorney general.” Id. In the case at bar, skincare product manufacturers such as Soleil are more proximate to the alleged competitive injury. These manufacturers have a stronger commercial interest to protect than does the Petitioner, making them more appropriate as private attorney generals. See Joint Stock, 266 F.3d at 182–83 (denying standing where plaintiff had not yet entered the U.S. vodka market). Adam’s Apple seeks relief solely because consumers allegedly chose a different brand of cosmetics than one it exclusively 18 distributes, not because consumers chose to shop at department stores or other “purveyor[s] of only cruelty-free cosmetics and skincare products.” (R.6) In fact, if there is substance to Adam’s Apple’s claim of harm, it is difficult to understand why Soleil has “not asserted any claim in [its] own right.” See Associated Gen., 459 U.S. at 542 n.47. Thus, the direct link between the alleged harm and another manufacturer obviates the need to empower Adam’s Apple to act as a private attorney general in this case. d. The Fourth Factor Weighs Against Standing Because Adam’s Apple’s Harm Is Speculative. While Adam’s Apple has provided figures indicating that its sales of Soleil products decreased by twenty percent since the introduction of Aphrodite’s Code of Conduct, such damages are inherently speculative. (R.6) As shown above, other theories may explain why Soleil has experienced a downturn in its sales. See supra I(C)(1). Due to the existence of other cosmetics manufacturers whose products could affect Soleil’s sales and the difficulty of determining the percentage of Adam’s Apple customers who were induced to purchase Aphrodite products, “it is hard to see how any damages awarded would not be highly speculative.” Procter & Gamble, 242 F.3d at 564; see also Phoenix of Broward, 441 F. Supp. 2d at 1251. Additionally, as a retailer, Adam’s Apple could have prevented most, if not all, of the alleged damages by stocking Aphrodite products.5 See Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 235 (“If the retailers responded to the artificially-increased popularity of Slick 50 that allegedly resulted from the false advertising campaign by stocking Slick 50, they would not have suffered any damages.”). Thus, the interest that Adam’s Apple had in During the period in which Soleil experienced a loss of sales, Adam’s Apple could have sold Aphrodite products as a “purveyor of only cruelty-free cosmetics and skincare products” without losing goodwill. (R.6) 5 19 preserving Soleil’s position in the industry appears to rely on loyalty rather than market economics. See id. (interest involved “appears to be a theoretical, rather than [an] actual economic interest” (citing Conte Bros. Auto., Inc. v. Quaker State-Slick 50, Inc., 992 F. Supp. 709, 715 (D.N.J. 1998))). As a retailer, Adam’s Apple is uniquely situated to protect itself against these potential harms. The fourth factor thus weighs against standing. e. The Fifth Factor Weighs Against Standing Because of the Risk of Duplicative Damages Where More Appropriate Remedies Exist. If Adam’s Apple is allowed standing in this case “not only could every competitor in the market sue,” but “there would be nothing to stop other companies not in direct competition . . . from suing.” Procter & Gamble, 242 F.3d at 564. Under Petitioner’s theory, any retailer of cosmetic products could sue based on a decrease in sales allegedly attributed to Aphrodite’s statements. See Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 235 (“[U]nder Appellants’ theory, every corner grocer in America alleging that his sales of one brand of chocolate bars have fallen could bring a federal action against the manufacturer of another brand for falsely representing the chocolate content of its product.”). Furthermore, other avenues of relief exist. In addition to a more properly filed suit under the Lanham Act by a cosmetics manufacturer, the Food and Drug Administration or Federal Trade Commission could vindicate the public interest in Adam’s Apple’s place. See also Phoenix of Broward, 441 F. Supp. 2d at 1251–52 (denying standing to competing fast-food retailers because an identifiable class of persons had already vindicated the public interest). Moreover, distributors such as Adam’s Apple and department stores could sue for fraud under state laws. Thus, 20 allowing prudential standing under the Lanham Act would risk broad and overlapping damages and a great increase in litigation. “Such an action hardly seems befitting of a statute that was designed primarily to resurrect the federal tort of unfair competition after it was consigned to the post-Erie ashheap.” Conte Bros., 165 F.3d at 235. Therefore, the fifth factor weighs against standing. All of the factors presented weigh against standing because Adam’s Apple’s alleged injury is not the type the Lanham Act sought to redress and because other parties are better suited to vindicate the public interest. In cases where no competitive injury exists, this Court will serve the purposes of the Lanham Act and prudential standing by steering potential “private attorney generals” toward more appropriate avenues of relief, such as state fraud statutes or administrative agencies with false advertising experience. See e.g. (R.1) (Adam’s Apple bringing a claim based on the Ames False Advertising Statute, 16 A.G.L. § 152); cf. Elk Grove, 542 U.S. at 12 (prudential standing considerations generally lead the Court to reject suits involving the rights of third parties or general abstract principles better shaped by the representative branches of government). Therefore, Adam’s Apple lacks prudential standing under the multi-factor test. D. Enforcing Congressional Limits to the Lanham Act Reduces Litigation of Tenuous Claims While Steering Ill-Situated Parties to More Appropriate Avenues of Relief. Prudential standing allows the judiciary “to limit access to the federal courts to those litigants best suited to assert a particular claim.” Gladstone Realtors, 441 U.S. at 100. The purpose of finding the most direct party to vindicate the public interest is twofold: (1) to prevent duplicative litigation from parties whose injury is minimal; and (2) to 21 prevent collateral estoppel from affecting a more suitable plaintiff who may later bring a claim. First, allowing claims from a non-competitor like Adam’s Apple would undermine the anti-competitive purpose of the Lanham Act by opening the floodgates to harassing litigation. In the absence of prudential limits that channel Lanham Act claims to parties suffering “competitive injury,” plaintiffs with attenuated harm could bring repetitive or disingenuous suits, exacting litigation costs and gaining leverage for settlement negotiations. Allowing ill-situated parties to use the Lanham Act as a coercive bargaining tool would defeat the Act’s purpose, undercutting fair competition where companies seek to reform their business practices. See infra (II)(D). Second, allowing an attenuated party to bring claims under the Lanham Act poses the risk that collateral estoppel could affect later parties who fall squarely within the scope of the Act. Adam’s Apple or a similarly attenuated party may be unsuccessful in its Lanham Act claim based on its unfamiliarity with the cosmetics market, thereby diluting a manufacturer’s ability to vindicate its competitive interests where a valid claim exists. Additionally, granting standing to distributors for suits against manufacturers would create conflicts of interest in this and future cases. Allowing a retail agent-distributor such as Adam’s Apple to bring suit against a manufacturer would act against prudential standing’s aim of isolating those litigants best suited to assert a particular claim. Additionally, the dangers posed by the potential misuse of the Lanham Act, as well as the existence of alternative avenues available to the plaintiff, counsel against finding standing here. Therefore, this Court should affirm the decision of the Ames Circuit Court of Appeals and deny standing on prudential grounds. 22 II. THIS COURT SHOULD NOT TREAT APHRODITE’S PUBLIC STATEMENTS AS COMMERCIAL SPEECH BECAUSE DOING SO WOULD SUPPRESS VALUABLE NONCOMMERCIAL SPEECH WITHOUT SUBSTANTIALLY BENEFITING CONSUMERS. In drawing the distinction between commercial and noncommercial speech, courts must balance society’s interest in protecting consumers against the First Amendment’s command that the freedom of speech not be abridged. In Bolger v. Youngs Drug Products Corporation, the Court struck the right balance between protecting against harm and not unduly infringing upon the freedom of speech. It identified three characteristics that together “provide[d] strong support” for a conclusion that speech was commercial in character: (1) it was in the form of an advertisement; (2) it referenced specific products or services; and (3) its creation or distribution was prompted by economic motivations. 463 U.S. 60, 66–67 (1982). In so doing, it isolated the category of speech most likely to produce a commercial harm: speech that affords little opportunity for debate or counter-speech before consumers act upon its message. Aphrodite’s statements about its policy on animal testing are not commercial because they allow for public scrutiny and response. Furthermore, treating a company’s statements concerning its beliefs and opinions as commercial speech yields two strong negative effects: it unduly chills valuable speech, and it perverts the purpose of the Lanham Act, changing it from a shield into a weapon. A. This Court Has Emphasized the Necessity of Limiting the Scope of the Commercial Speech Category to Avoid Suppressing Non-Commercial Speech. 23 This Court has declared only a few areas of communication to be beyond the reach of the First Amendment. Bose Corp. v. Consumers Union of the U.S., Inc., 466 U.S. 485, 503 (1984) (stating that there are “few classes of ‘unprotected’ speech”). In general, “[b]ecause the line between unconditionally guaranteed speech and speech that may legitimately be regulated is a close one,” separating the two categories of speech “calls for sensitive tools.” Se. Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad, 420 U.S. 546, 561 (1975) (quoting Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513, 525 (1958)). In an inquiry like this one, the threshold question is whether speech is commercial or non-commercial. See Bolger, 463 U.S. at 65. The importance of this primary distinction can be somewhat obscured, however, by the fact that in most of the commercial speech cases decided by the Court, the parties have stipulated that the speech at issue was commercial. See, e.g., Thompson v. W. States Med. Ctr., 535 U.S. 357, 366 (2002); Cent. Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Pub. Serv. Comm’n of N.Y., 447 U.S. 557, 568 (1980). In these cases, the lack of dispute regarding the commercial character of the speech led the Court to focus its inquiry on a secondary question regarding the protection afforded to commercial speech under the First Amendment. To establish whether commercial speech is protected in this narrower inquiry, the Court asks whether the speech is false or misleading. See Cent. Hudson, 447 U.S. at 566 (establishing that commercial speech “at least must concern lawful activity and not be misleading” to be protected under the First Amendment). However, where the commercial character of speech is contested, the fact that the speech is allegedly false or misleading is immaterial to the threshold question of whether the speech is commercial. See Kasky v. Nike, Inc., 24 45 P.3d 243, 265 n.2 (Cal. 2002) (Chin, J., dissenting), cert. denied, Nike, Inc. v. Kasky, 539 U.S. 654 (2003). Petitioner argues that under current doctrine “there is a risk that false or misleading commercial speech could evade regulation,” and that certain tests might allow some speech to “slip through the regulatory cracks.” (Petr.’s Br. 25, 29) Consistent with the greater thrust of First Amendment doctrine, however, this Court has been less concerned that negative speech might “slip through” than that regulation might stifle valuable speech. As Justice Stevens explained in concurrence and a majority of the Court later echoed: “[b]ecause ‘commercial speech’ is afforded less constitutional protection than other forms of speech, it is important that the commercial speech concept not be defined too broadly lest speech deserving of greater constitutional protection be inadvertently suppressed.” Cent. Hudson, 447 U.S. at 579 (Stevens, J., concurring); see also Bolger, 463 U.S. at 66 (1983). Therefore, precedent and concern for First Amendment values dictate that, when considering close questions, this Court should err on the side of granting speech full non-commercial protection. B. This Court’s Bolger Test Successfully Distinguishes Commercial from NonCommercial Speech and Demonstrates that Aphrodite’s Speech Should Not Be Considered Commercial. Though this Court has not relied exclusively on one test for commercial speech, it has long recognized a “common-sense distinction” between “speech proposing a commercial transaction . . . and other varieties of speech.” Ohralik v. Ohio State Bar Ass’n, 436 U.S. 447, 455–456 (1978). Unlike non-commercial speech, commercial speech affords consumers little opportunity for debate or reflection. In this respect, false or misleading commercial speech is more likely to cause harm to the public than similar 25 noncommercial speech. As Justice Stevens articulated, “because commercial speech often occurs in the place of sale, consumers may respond to the falsehood before there is time for more speech and considered reflection to minimize the risks of being misled.” Rubin v. Coors Brewing Co., 514 U.S. 476, 496 (1995) (Stevens, J., concurring). It is this risk that justifies heightened regulation of commercial speech. This Court offered its most thorough analysis of the process of dividing commercial from non-commercial speech in Bolger v. Youngs Drug Products. This analysis allows courts to separate speech that presents a likelihood of causing commercial harm from speech that can be remedied with more speech. Cf. Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357, 377 (1927) (“[T]he remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.”) 1. The Bolger Test Allows Courts to Identify the Kind of Speech Likely to Cause Harm to Consumers. In Bolger, the Court faced the question of how to classify pamphlets which a manufacturer of prophylactics sought to send unsolicited through the United States mail. 463 U.S. at 62. Some of the pamphlets contained only basic product and price information, while others contained more general information about venereal diseases. Id. at 67 nn.12-13. The Bolger Court began its analysis by stating that the “mere fact” that the pamphlets were “concededly advertisements” did not make them commercial speech. Id. at 66 (citing New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964)). Second, the Court indicated that a reference to a specific product does not automatically make a communication commercial. Id. Third, citing three Supreme Court precedents, the Court stated that the fact that the speaker has an economic motivation would “clearly be 26 insufficient by itself” to identify commercial speech. Id. at 67 (citations omitted). While the Court did not require that each of the three factors be present for speech to be commercial, id. at 68 n.14, it explained that “the combination of all these characteristics . . . provides strong support” for designating speech as commercial. Id. at 67. This analysis is often characterized as a “test.” See, e.g., Procter & Gamble, 242 F.3d at 547 (“Our application of the Bolger test is what ultimately determines whether the speech is commercial.”). The three prongs of this test are understood to be: (1) if the communication is in the form of an advertisement; (2) if it references specific products or services; and (3) if its creation or distribution was prompted by economic motivations. 463 U.S. at 66–67. However, analysis of Bolger suggests that these prongs should not receive equal weight. Economic motivation may be a necessary factor to a finding of commercial speech. See Associated Students for Univ. of Cal. at Riverside v. Atty. Gen., 368 F. Supp. 11, 24 (C.D. Cal. 1973) (declining to allow prosecution of distribution of advertising of prophylactics by students who had no financial interest in sales). However, by the time of Bolger, a line of cases establishing the rights of companies to speak freely, see infra II(C)(1), and strong voices within the Court counseled against putting too much weight on this factor, see, e.g., Central Hudson, 447 U.S. at 580 (Stevens, J., concurring) (“Economic motivation could not be made a disqualifying factor [from maximum protection] without enormous damage to the first amendment.” (quoting Daniel Farber, Commercial Speech and First Amendment Theory, 74 Nw. U. L. Rev. 372, 382–83 (1979))). 27 In contrast, the focus on context implicit in the first two factors accords with the Court’s consistent distinction between speech that offers an opportunity for others to respond from speech that offers no such opportunity. For example, in Ohralik, the Court distinguished the advertisement of routine legal services upheld in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 433 U.S. 850 (1977), from an in-person solicitation for representation in a hospital, which did not allow time for reflection. 436 U.S. at 454–55. The emphasis on context can also be seen in the oft-cited case of Gordon & Breach Science Publishers S.A., STBS, Ltd. v. American Institute of Physics, 859 F. Supp. 1521 (S.D.N.Y. 1994). In Gordon, the court held that speech which was “exactly the type of consumer or editorial comment that raise[s] free speech concerns,” id. at 1544 (internal quotation marks omitted) (alteration in original), became commercial when it was distributed for promotional purposes. Id. Cf. Semco, Inc. v. Amcast, Inc., 52 F.3d 108, 114 (6th Cir. 1995) (holding that, regardless of whether self-promoting article was commercial, the distribution of it at a trade show would make it so). 2. Aphrodite’s Speech Satisfies the Bolger Test. Aphrodite’s statements are not commercial under the standards outlined in the Bolger test. First, Aphrodite’s communications did not resemble traditional advertisements in form or effect. Aphrodite is skilled in creating advertising campaigns, (R.3) (describing its successful “Be Beautiful” campaign), but it chose not to communicate its policy about animal testing through that medium. Instead, it sought to engage the public through the press—a much less reliable method of dissemination if it desired to promote a commercial transaction. Aphrodite did include its Code of Conduct 28 on its website (R.4), but this is hardly a directed action along the lines of unsolicited advertising. Second, Aphrodite’s communications were not tied to its products. The company neither mentioned specific products in press releases nor announced its animal testing policy on product labels. Finally, while the company may have been economically motivated to some extent, the connection between the communications and the economic reward is much less direct than in typical commercial speech. In addition, Aphrodite’s speech is highly susceptible to scrutiny and counterspeech—precisely those features that are absent from speech traditionally regarded as commercial in nature. A consumer reading a label may act on the information provided before someone—the media or a consumer advocacy group—can enter to debate the issue or present evidence to the contrary. This relative invulnerability to debate and counter-speech is a distinctive element of commercial speech, and one that increases the risks of harm to consumers. Unlike canonical commercial speech, Aphrodite’s speech is fundamentally about public issues. The content of Aphrodite’s speech focuses on how it as a company has chosen to approach animal testing and corporate responsibility. By engaging important issues that already receive significant public concern and attention, Aphrodite invited the criticism of the media, consumer advocates, and animal rights groups. Aphrodite’s choice to discuss issues of public concern rather than to propose a commercial transaction militates against a conclusion that Aphrodite’s statements are commercial speech. C. An Expansive Test for Commercial Speech Would Have a Chilling Effect on Valuable Speech. 1. Defining Commercial Speech According to the Corporate Identity of the Speaker Is Not Consistent with Precedent. 29 Labeling Aphrodite’s speech as commercial is tantamount to treating all speech by a corporate speaker as commercial speech. This classification runs contrary to the Court’s precedent regarding First Amendment protection for corporate speakers. This Court has held that the corporate identity of a speaker does not affect the extent of its protection under the First Amendment. For example, in New York Times Co., Justice Brennan rejected the argument that an advertisement published in The New York Times deserved lower First Amendment protection due to the paper’s financial interest in the speech. See 376 U.S. at 265–66. Additionally, in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, the Court described banks’ attempts to be heard on the issue of new taxes as “the type of speech indispensable to decision-making in a democracy” and noted that “this is no less true because the speech comes from a corporation rather than an individual.” 435 U.S. 765, 777 (1978). Furthermore, this Court has justified granting statements made in the context of commercial transactions only limited protection based on the full First Amendment protection for other speech by corporations. See Cent. Hudson, 447 U.S. at 563 n.5 (stating that companies “enjoy the full panoply of First Amendment protections for their direct comments on public issues. There is no reason for providing similar constitutional protection when such statements are made only in the context of commercial transactions.”) (citing Consol. Edison Co. of N.Y., Inc. v. Pub. Serv. Comm’n of N.Y., 447 U.S. 530, 533–34 (1980)). 2. Labeling Aphrodite’s Speech as Commercial Will Have a Chilling Effect on the Non-Commercial Speech of Corporations. While “[u]ntruthful speech, commercial or otherwise, has never been protected for its own sake,” Va. State Bd. of Pharm. v. Va. Citizens Consumer Council, Inc., 425 30 U.S. 748, 771 (1976), this Court has recognized that “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate” and that “it must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the breathing space they need to survive,” N.Y. Times, 376 U.S. at 271–72 (internal citation and quotation marks omitted). This Court has been less concerned with providing breathing space in the commercial context because of its perception that commercial speech is hardier than other types of speech. See Va. State Bd., 425 U.S. at 772 n.24. (“[C]ommercial speech may be more durable than other kinds. Since advertising is the sine qua non of commercial profits, there is little likelihood of its being chilled by proper regulation.”); see also Cent. Hudson, 447 U.S. at 564 n.6. However, when the speech that might be chilled is non-commercial, the rationale for limiting breathing space does not apply. Bd. of Trs. of the State Univ. of N.Y. v. Fox, 492 U.S. 469, 481–82 (1989) (“Although it is true that overbreadth analysis does not normally apply to commercial speech . . ., that means only that a statute whose overbreadth consists of unlawful restriction of commercial speech will not be facially invalidated on that ground. . . . Here, however, . . . the alleged overbreadth . . . consists of its application to non-commercial speech, and that is what counts.”) Because such noncommercial speech by a corporation is not directly connected to financial gain, it is not durable and can be chilled. The likelihood of a chilling effect is substantially greater in the context of a private action like the one at hand. In contrast to government regulations that are applied with relative uniformity, private actions proceed piecemeal through the adjudication of individual actions, thereby complicating corporations’ assessments of liability. Recognizing the particular dangers associated with private actions, Justice Breyer has noted: “Uncertainty about how a court will view . . . statements, can easily chill a 31 speaker’s efforts to engage in public debate—particularly where a ‘false advertising’ law . . . imposes liability based upon negligence or without fault.” Nike, 539 U.S. at 680 (Breyer, J., dissenting from the denial of certiorari); see also Riley v. Nat’l Fed. of the Blind of N.C., Inc, 487 U.S. 781, 793–94 (1988) (arguing that speakers cannot “be made to wait years before being able to speak with a measure of security”) (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). “That threat means a commercial speaker must take particular care—considerably more care than the speaker’s noncommercial opponents— when speaking on public matters.” Nike, 539 U.S. at 680 (Breyer, J., dissenting from the denial of certiorari). If speech such as Aphrodite’s is considered commercial, companies will limit their risk of liability by restricting the public dissemination of information related to their corporate activities. This chilling effect will curtail valuable corporate speech previously determined to merit full First Amendment protection. 3. This Court Should Not Attempt to Dissect Aphrodite’s Speech Because Any Commercial Elements Are Inextricably Intertwined with Non-Commercial Elements. Even if this Court were to decide that Aphrodite’s speech about animal testing contained commercial elements, these are inextricably intertwined with non-commercial ones. This Court has held that such “inextricably intertwined” speech must be treated as if the whole were non-commercial. Riley, 487 U.S. at 796 (expressing concern for “the reality” that the charitable solicitations in that case were “characteristically intertwined with informative and perhaps persuasive speech” (quoting Vill. of Schaumburg v. Citizens for a Better Env’t, 444 U.S. 620, 632 (1980))). Because of the danger of chilling 32 this valuable speech, the Court declined to “parcel out the speech, applying one test to one phrase and another test to another phrase.” Id. at 786. Aphrodite’s statements about animal testing and corporate responsibility both describe what the company stands for and contribute to public debate; as such, they are not mere “references to public issues.” Bolger, 463 U.S. at 68. These statements can therefore be distinguished from the cases cited by Petitioner, in which the facts support a suspicion that the non-commercial element had been added solely for the purpose of immunizing the speech. See, e.g., Fox, 492 U.S. at 474-75 (declining to find sales of Tupperware inextricably intertwined with a home economics lesson); United States v. Bell, 414 F.3d 474, 480 n.6. (3d Cir. 2005) (separating the sale of advice in preparing fraudulent tax returns from speech criticizing the United States tax code). The difficulty of separating non-commercial representations concerning beliefs and opinions with possible commercial elements is particularly evident from the Petitioner’s complaint. Petitioner charges that Aphrodite’s “representations that it opposes animal testing” are false and misleading. (R.6) Petitioner thus targets as commercial Aphrodite’s statement of opinion on an important public issue—the very speech assumed to be at the “core” of the First Amendment. Dun & Bradstreet, Inc. v. Greenmoss Builders, Inc., 472 U.S. 749, 758–59 (1985) (“It is speech on matters of public concern that is at the heart of the First Amendment’s protection.” (quoting Bellotti, 435 U.S. at 776) (internal quotation marks omitted)). Even if courts separate out such allegations and only allow falsifiable claims to go to trial, the burden of combating such expansive allegations will cause many companies to unnecessarily limit their public engagement. 33 D. Labeling Aphrodite’s Comments Commercial Speech Would Subvert the Purpose of the Lanham Act, Distort the Competitive Market, and Harm Consumers by Inviting Companies to Use False Advertising Suits to Seek Competitive Gains. Petitioner’s theory of commercial speech would contravene the regulatory purpose of the statute upon which it stakes its claim. Having evolved from an antitrademark infringement mechanism into a deterrent against unfair competition, the current Act regulates commercial speech for the purpose of facilitating a fair market for consumers and competitors alike. See 15 U.S.C. § 1127 (2000) (“The intent of this chapter is to . . . protect persons engaged in such commerce against unfair competition.”). It should not, as would be the case under Petitioner’s test, become an alternative means for rivals to pursue their competitive goals. If the Lanham Act is to protect the commercial market against the distorting effects of unfair competition, courts must in turn protect the Act against those who would abuse it to seek an advantage over their rivals. Yet by accusing companies of false factual statements, an opportunistic rival can force competitors into a prolonged and expensive struggle. See, e.g., Am. Home Prods. Corp. v. Johnson & Johnson, 654 F. Supp. 568, 571 (S.D.N.Y. 1987) (“Small nations have fought for their very survival with less resources and resourcefulness than these antagonists”); Israel Travel Advisory Serv., Inc. v Israel Identity Tours, Inc., 61 F.3d 1250, 1253 (7th Cir. 1995) (“We have a spite match, and as in many such contests, the parties have raised every imaginable claim and others that exceed the bounds of imagination.”). The powerful tool that the Lanham Act potentially gives to economic rivals requires courts to apply the “commercial” label with care. An over-inclusive definition of commercial speech would enable companies to 34 challenge any one of a competitor’s thousands of public statements under the Lanham Act’s strict liability regime. Since noncommercial speech falls outside the Act’s ambit, the Court’s ability to ensure that the Act functions properly turns on its construction of commercial speech. If a competitor can characterize almost any of a corporate rival’s statements as commercial, it becomes too easy to raise a claim to achieve disruptive effects. See First Health Group Corp. v. BCE Emergis Corp., 269 F.3d 800, 806 (7th Cir. 2001) (warning that “[s]uits by rivals are not necessary for deterrence but could be used to harass a competitor and stifle the competitive process.”).6 Even purported efforts to “correct” false noncommercial statements provide rivals with a means to embark on fishing expeditions. In its complaint, Petitioner alleges that Aphrodite lied when it claimed to be “morally opposed to animal testing” and an “industry leader on the issue of animal testing.” (R.6) These allegations are so subjective that Aphrodite could only defend the truth of its ethos by expending substantial resources—enough to divert its attention from competing to its full capacity. In Aphrodite’s case, the risk that the Court might allow such opportunistic behavior is particularly dangerous. Adam’s Apple’s suit is not about animal testing, protecting consumers, or even changing Aphrodite’s procedures. It is about dollars and cents. If successful, Adam’s Apple stands to gain up to three times its purported lost revenue. See 15 U.S.C. § 1117 (2004) (“the court may enter judgment . . . for any sum above the amount found as actual damages, not exceeding three times such amount.”). 6 See also Jean Wegman Burns, Confused Jurisprudence: False Advertising Under the Lanham Act, 79 B.U. L. Rev. 807, 880 (1999) (expressing concern that, by too easily allowing competitors to “sue over a rival’s alleged advertising misrepresentation, whether intentional or innocent, courts have opened the door to lawsuits intended more to harm a rival and diminish competition than aid consumers.”). 35 This gives Adam’s Apple a significant financial incentive to address in the courtroom what ought to be addressed through economic competition alone. Such behavior runs counter to the principle that the Act should prevent, and not permit, companies from deviating from the standards of fair competition. Treating Aphrodite’s public advocacy against animal testing as commercial speech would lend legitimacy to anti-competitive behavior. Petitioner’s emphasis on maintaining the market’s integrity does not alter the reality that allowing it to use Aphrodite’s noncommercial speech to trigger Lanham Act liability would transform the Act into a tool of competition. The Act would thus be transformed from a defense against trademark infringement into a weapon for unfair competitive advancement. 36 CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, this court should affirm the ruling of the Court of Appeals for the Ames Circuit, and dismiss the petitioner’s complaint. Respectfully submitted, ______________________________ Elizabeth Edmondson ______________________________ Mark Jensen ______________________________ Tian Tian Mayimin ______________________________ Samuel Miller ______________________________ S. Chartey Quarcoo ______________________________ Kevin Terrazas 37