searching-for-lithuanian-identity-between-east-and-west-chapter

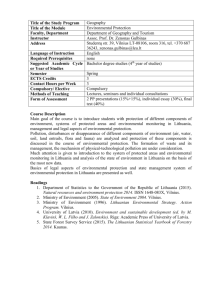

advertisement