In as much as the word “utopia” means “no place”, Thomas More's

advertisement

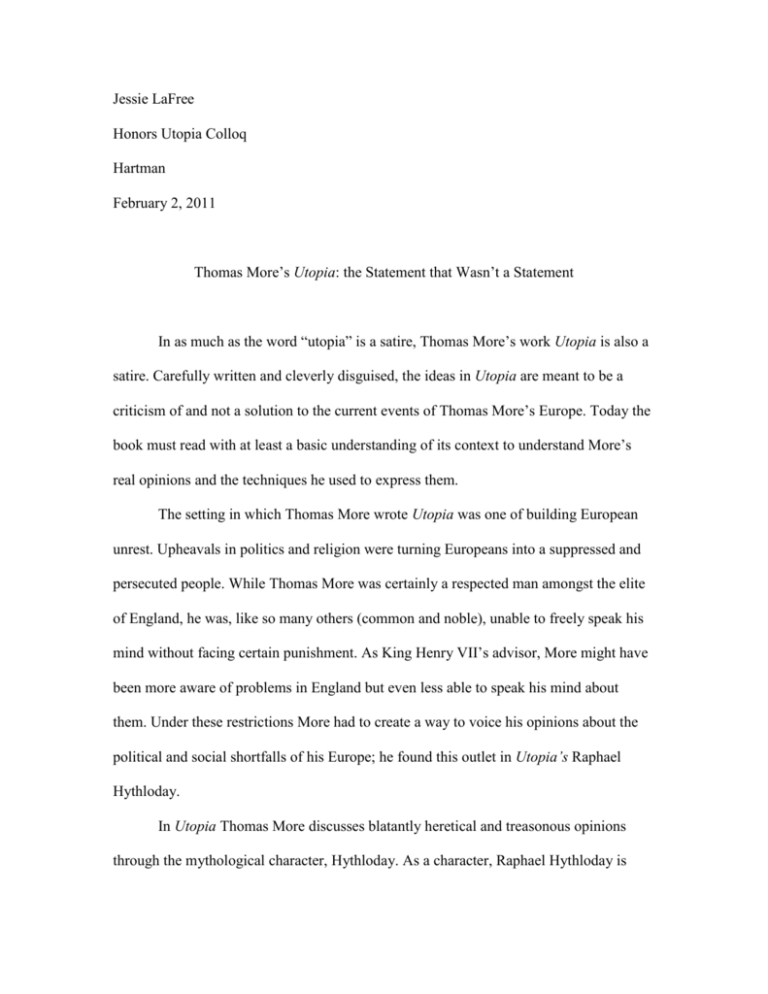

Jessie LaFree Honors Utopia Colloq Hartman February 2, 2011 Thomas More’s Utopia: the Statement that Wasn’t a Statement In as much as the word “utopia” is a satire, Thomas More’s work Utopia is also a satire. Carefully written and cleverly disguised, the ideas in Utopia are meant to be a criticism of and not a solution to the current events of Thomas More’s Europe. Today the book must read with at least a basic understanding of its context to understand More’s real opinions and the techniques he used to express them. The setting in which Thomas More wrote Utopia was one of building European unrest. Upheavals in politics and religion were turning Europeans into a suppressed and persecuted people. While Thomas More was certainly a respected man amongst the elite of England, he was, like so many others (common and noble), unable to freely speak his mind without facing certain punishment. As King Henry VII’s advisor, More might have been more aware of problems in England but even less able to speak his mind about them. Under these restrictions More had to create a way to voice his opinions about the political and social shortfalls of his Europe; he found this outlet in Utopia’s Raphael Hythloday. In Utopia Thomas More discusses blatantly heretical and treasonous opinions through the mythological character, Hythloday. As a character, Raphael Hythloday is shallow and mysterious; a character entirely fabricated by More and the perfect bearer for More’s controversial statements. Over the course of the novel, Hythloday discusses the many “perfections” of Utopian society. He discusses the sharing of food amongst the people and the disregard for material goods. He describes a whole people who are interested in education and tolerant of religions. Marriage is sacred to the Utopians but politicians and lawyers receive no more respect than any other. Wars are only begun with sure purpose and the people as a whole hold power over their leaders. In identifying these ideals through Hythloday, More silently identifies their counterparts in European Society: maltreatment, ostentation, ignorance, intolerance, adultery, misuse of power, and corruption among others. By inadvertently bringing up such topics through Hythloday's stories More, in a sense, "saves himself" from persecution, religious or political. This tactic is compounded by his ambiguous closing comments where he claims to like and dislike certain aspects of Utopia without disclosing what they are. More says what he needs to say through a fictional character but excludes writing his own opinion on the matters at hand concretely. In no way is More recommending the Utopian way of life through Utopia; nor is he attempting to offer solutions to the problems present in Europe during his time. Instead, More is bringing attention to those problems. Utopia creates a fictional world upon which readers (in More's time) were meant to compare and reflect on in relation to their own society and through their own means. Comments Jessie, You have a strong and clearly stated thesis in this essay, that the book should be read as social criticism and not as a proposal. Your discussion of the reasons for More’s ambiguity suggests why he had to disguise his intent with fiction. I’m not sure, though, why you think the book should not be read as proposing solutions. You state this very strongly: In no way is More recommending the Utopian way of life through Utopia; nor is he attempting to offer solutions to the problems present in Europe during his time. Do you ever say why he is not offering solutions? Or am I just missing it?