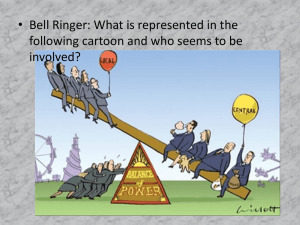

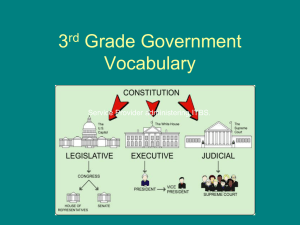

click here for unit 4 - Butler Area School District

advertisement