Chapter 1

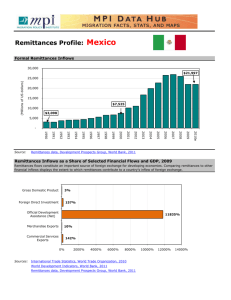

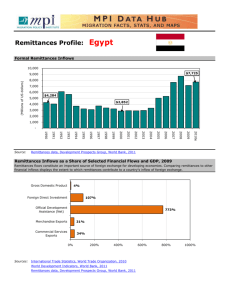

advertisement