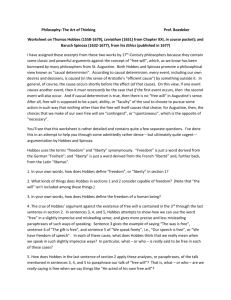

Chapter 3 - Tolerance and affect _final draft_

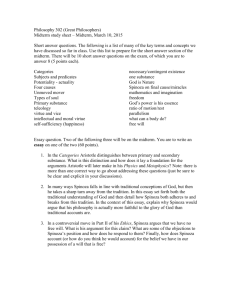

advertisement