handout (.doc) - Backdoor Broadcasting Company

advertisement

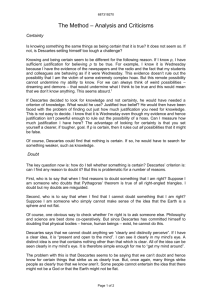

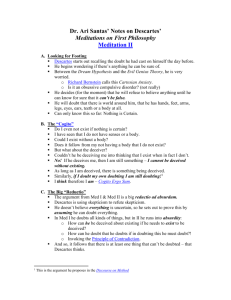

1 Texts for “Epistemology Past and Present,” John Carriero, UCLA TEXT 1) Spinoza, TdIE, §§ 19-20: 1. There is the perception we have from hearsay, or from some sign conventionally agreed upon. 2. There is the perception that we have from casual experience; that is, experience that is not determined by the intellect, but is so called because it chances thus to occur [casu sic occurrit], and we have experienced nothing else that contradicts it, so that it remains in our minds unchanged. 3. There is the perception we have when the essence of a thing is inferred from another thing, but not adequately. This happens either when we infer a cause from some effect or when an inference is made from some universal which is always accompanied by some property. 4. Finally, there is the perception we have when a thing is perceived through its essence alone, or through knowledge of its proximate cause. All these I shall illustrate with examples. By hearsay alone I know [scio] the date of my birth, who my parents were, and things of that sort, which I have never doubted. By casual experience I know [scio] that I shall die; this I affirm because I have seen that others like me have died, although they have not all lived to the same age nor have died from the same disease. Again, by casual experience I know [scio] that oil has the property of feeding fire, and water of extinguishing it. I know that a dog is a barking animal and man a rational animal. And it is in this way that I know [novi] almost everything that is of practical use in life. TEXT 2) Spinoza, 2p41: Cognition [cognitio] of the first kind is the only cause of falsity; cognition of the second and third kind is necessarily true. TEXT 3) Leibniz, Monadology, § 28: Men function like beasts [i.e., lower animals] insofar as the connections among their perceptions come about only on the basis of memory, resembling empirical physicians who have mere practice without theory. We are all mere empirics in three-quarters of our actions. For example, when one expects a sunrise tomorrow, one acts as an empiric, seeing that this has always been so heretofore. Only the astronomer judges this by reason. [Rescher, 106-107] 2 PNG, § 5: Men too, insofar as they are empirics, that is to say, in three-fourths of their actions, act only like beasts. For example, we expect day to dawn tomorrow because we have always experienced this to be so; only the astronomer predicts it with reason, and even his prediction will ultimately fail when the cause of daylight, which is by no means eternal, stops. But reasoning in the true sense depends on necessary or eternal truths, as those of logic, number, and geometry, which make the connections of ideas indubitable and their conclusions infallible. Animals in which such consequences cannot be observed are called beasts, but those who know these necessary truths are the ones properly called rational animals, and their souls are called spirits. TEXT 4) Spinoza, at the end of 2p28dem: Therefore, these ideas of affections, insofar as they are related only to the human mind, are like conclusions without premises; that is, as is self-evident, confused ideas. TEXT 5) Leibniz’s notes on Descartes’s Principles: On Article 5. There can be no doubt in mathematical demonstrations except insofar as we need to guard against error in our arithmetical calculations . . . [Loemker, 384] On Article 13. I have already observed, on Article 5, that the errors which can arise from defective memory or attention and which can also occur in arithmetical calculations even after a perfect method has been found, as in numbers, have been mentioned here to no purpose, since no method can be devised in which such errors are not to be feared, especially when the reasoning is long drawn out. So one must resort to criteria. For the rest, God seems to be called in here merely as a kind of display or showpiece, not to mention that strange fiction or doubt as to whether we are not led to err even in the most evident things [evidentissimis], which should convince no one because the nature of evidence [natura evidentiae] prevents it and the experiences and successes of the whole of life witness against it. TEXT 6) Spinoza, 2p47s: That men do not have as clear knowledge of God as they do of common notions arises from the fact that they are unable to imagine God as they do bodies, and that they have connected the word God with images of things which they commonly see; and this they can scarcely avoid, being affected continually by external bodies. Indeed, most errors result solely from the incorrect application of words to things. When somebody says that the lines joining the center of a circle to its circumference are unequal, he surely 3 understands [intelligit] by circle, something different from what mathematicians understand. Likewise, when men make mistakes in arithmetic, they have different figures in mind from those on paper. So if you look only into their minds, they indeed are not mistaken; but they seem to be wrong because we think that they have in mind the figures on the page. If this were not the case, we would not think them to be wrong, just as I did not think that person to be wrong whom I recently heard shouting that his hall had flown into his neighbor’s hen, for I could see clearly what he had in mind. [Cf. Spinoza, TdIE, § 79: Hence it follows that it is only when we do not have a clear and distinct idea of God that we can cast doubt on our true ideas on the grounds of the possible existence of a deceiving God who misleads us even in things most certain. That is, this can happen only if, attending to the knowledge [cognitionem] we have of the origin of all things, we find that there is nothing to convince us that he is not a deceiver, with the same conviction that we have when, attending to the nature of a triangle [the “gold” standard], we find that its three angles are equal to two right angles. But if we do possess such knowledge of God [cognitionem] as we have of a triangle, all doubt is removed. And just as we can attain such knowledge [cognitionem] of a triangle although not knowing [sciamus] for sure whether some arch-deceiver is deceiving us, so too we can attain such knowledge [cognitionem] of God although not knowing [sciamus] for sure whether there is some arch-deceiver. Provided we have that knowledge, it will suffice, as I have said, to remove all doubt that we may have concerning clear and distinct ideas.] TEXT 7) Spinoza 2p43: He who has a true idea knows at the same time that he has a true idea, and cannot doubt its truth. From 2p43s: For nobody who has a true idea is unaware that a true idea involves absolute certainty. To have a true idea means only to know a thing perfectly, that is, to the utmost degree. Indeed, nobody can doubt this, unless he thinks that an idea is some dumb thing like a picture on a tablet, and not a mode of thinking, to wit, the very act of understanding [nempe ipsum intelligere]. And who, pray, can know [scire] that he understands [intellegere] something unless he first understands it? That is, who can know that he is certain of something unless he is first certain of it? Again, what standard of truth can there be that is clearer and more certain than a true idea? Indeed, just as light makes manifest both itself and darkness, so truth is the standard of both truth and falsity. 4 TEXT 8) Descartes, from the Fifth Meditation: Not only are all these things [viz. continuous quantity, its extension, sizes, shapes, positions, and local motions] known and transparent to me when regarded in this general way, but in addition there are countless particular features regarding shape, number, and motion and so on, which I perceive when I give them my attention. And the truth of these matters is so open and so much in harmony with my nature, that on first discovering them it seems that I am not so much learning something new as remembering what I knew before; or it seems like noticing for the first time things which were long present within me although I had never turned my mental gaze [obtutum mentis] on them before. [¶4; 7:63-64; 2:44] TEXT 9) From Burman’s notes of a conversation with Descartes: [Descartes] . . . For since the cause is itself being and substance, and it brings something into being, i.e., out of nothing (a method of production which is a prerogative of God), what is produced must at the very least be being and substance. To this extent at least, it will be like God and bear his image. [Burman] But in that case even stones and suchlike are going to be in God’s image. [Descartes] Even these things do have the image and likeness of God, but it is very remote, minute and indistinct. [5:156; 3:340] TEXT 10) From Barry Stroud’s The Significance of Philosophical Scepticism: That conclusion [external-world skepticism] can be avoided, it seems to me, only if we can find some way to avoid the requirement that we must know that we are not dreaming if we are to know anything about the world around us. But that requirement cannot be avoided if it is nothing more than an instance of a general procedure we recognize and insist on in making and assessing knowledge-claims in everyday and scientific life. We have no notion of knowledge other than what is embodied in those procedures and practices. So if that requirement is a ‘fact’ of our ordinary conception of knowledge we will have to accept the conclusion that no one knows anything about the world around us. [p. 31] TEXT 11) Locke, Essay Concerning Human Understanding: 5 If by this Enquiry into the Nature of the Understanding, I can discover the Powers thereof; how far they reach; to what things they are in any Degree proportionate; and where they fail us, I suppose it may be of use, to prevail with the busy Mind of Man, to be more cautious in meddling with things exceeding its Comprehension; to stop, when it is at the utmost Extent of its Tether; and to sit down in a quiet Ignorance of those Things, which, upon Examination, are found to be beyond the reach of our Capacities. TEXT 12) Hume, A Treatise Concerning Human Nature: . . . any hypothesis, that pretends to discover the ultimate original qualities of human nature, ought at first to be rejected as presumptuous and chimerical (p. xvii) But if this impossibility of explaining ultimate principles should be esteemed a defect in the science of man, I will venture to affirm, that ’tis a defect common to it with all the sciences . . . (p. xviii) TEXT 13) Descartes, from Meditation IV: Now when I do not perceive clearly and distinctly enough, then if I abstain from bringing my judgment to bear, it is clear that I act correctly [recte] and am not deceived. But if in such cases I either affirm or deny, then I am not using my free will [libertate arbitrii] correctly [recte]. If I go for the alternative which is false, then obviously I shall be in error; if I take the other side, then it is by pure chance [casu quidem] that I arrive at the truth, and I shall still be at fault since it is clear by the natural light that the perception of the intellect should always precede the determination of the will. [¶12; 7:59-60; 2:41] TEXT 14) Kant, A Critique of Pure Reason: The famous Locke . . . because he encountered pure concepts of the understanding in experience, also derived them from this experience, and thus proceeded so inconsistently that he thereby dared to make attempts at cognitions that go far beyond the boundary of all experience. David Hume recognized that in order to be able to do the latter it is necessary that these concepts would have to have their origin a priori. But he could not explain at all how it is possible for the understanding to think of concepts that in themselves are not combined in the understanding as still necessarily combined in the object, and it never occurred to him that perhaps the understanding itself, by means of these concepts, could be the originator of the experience in which its objects are encountered, he thus, driven by necessity, derived them from experience (namely from a subjective necessity arisen from frequent association in experience, which is subsequently falsely held to be objective, i.e., custom); however he subsequently 6 proceeded quite consistently in declaring it to be impossible to go beyond the boundary of experience with these concepts and the principles they occasion. The empirical derivation, however, to which both of them resorted, cannot be reconciled with the reality of the scientific cognition a priori that we possess, that namely of pure mathematics and general natural science, and is therefore refuted by the fact. [B127128]