Changing the broken record: New theory and data on Maori offending

Simone Bull

Introduction

Despite being experts in criminal justice, when we gauged how well we know

Maori representation in the criminal justice system at the recent IPS evidence

forum, our knowledge was shown to be seriously lacking. This is reflected in

the sparse literature on the topic.

Existing theory

Few explanations for the seemingly high levels of offending by Māori have

been the object of rigorous research in New Zealand - although many have

been the subject of "rigorous assertion" (Stenning, 2005).

Over the past century, the volume of literature generated by Maori offending is

such that you could list most of the references on one page. The drivers of

crime specified in that literature range from atavism to tradition and cultural

mores; urbanisation, cultural discontinuity, failed integration, acculturation

stress, social disorganisation, and lifestyle instability; primary and secondary

culture conflicts; colonial injustices, institutional racism, tradition corrupted,

cultural denigration and powerlessness; poor education outcomes (sometimes

involving glue ear) and socio-economic deprivation; whānau alienation, stress,

alcohol and drug abuse; necessity, excitement, consumerism; politicisation

and decolonisation; and, most recently, trapped lifestyles (complex interplay

between socio-economic variables, confused or partially developed cultural

identities, and individual and collective experiences).

Bias and the age structure of the population have also been identified as

critical issues for Maori. But, I view them not as explanations of offending so

much as [partial] explanations of the extent of Maori representation in the

criminal justice system (though General Strain Theory does posit bias as a

motivation for crime).

I don’t have the space here to review or critique this literature. At the risk of

over-simplifying, I want to focus on key themes.

Key theme 1: Maori 'over-representation' is the wrong paradigm

The bulk of published literature on the causes of Maori offending consists of

general (as opposed to offence-specific) theories that try to explain all Maori

offending. Most start with the observation that Maori are over-represented in

the criminal justice system, and work from there. But, how robust is this claim?

On the surface, it seems valid. While making up only 15% of the general

population, Maori currently comprise 40-45% of all Police apprehensions.

Therefore, Māori are over-represented in the criminal justice system. On the

other hand, this view of Maori over-representation ignores the roles played by

known criminogenic factors. Rather than compare the proportion of Māori

apprehensions to the proportion of Māori in the general population, for

example, we should examine whether the proportion of Māori who are young,

male, unmarried, unemployed, uneducated, in substandard housing, is

reflected in the apprehension statistics. Rates of recorded offending, and

hence imprisonment, are well known to depend on a range of social

development factors (Braithwaite, 1989), rather than raw population

proportions. But, we have never undertaken research to test whether Maori

are still over-represented in the criminal justice system once you control for

known criminogenic variables.

Key theme 2: Perceptions of Maori offending are distorted

It is my conjecture that, as far as our perceptions of Maori offending are

concerned, reality has been overtaken by stereotypes and assorted

misinformation much of which is generated by corporate media. In the book

Simulacra and Simulation (1995), French social theorist Jean Baudrillard

refers to this state of affairs as hyper-reality. Unfortunately, this hyper-reality

(rather than a sound evidence base) has become the starting point for much

research and policy. Our ability to correct this requires us to fully utilise the

available evidence.

Key theme 3: Existing data is under-utilised

Braithwaite (1989) identified 13 powerful associations that all general theories

of crime need to account for. These include, for example, the observation that

80% of reported offending is committed by males, and that crime is

disproportionately committed by those aged between 15 and 25 years. In New

Zealand, the data needed to characterise Maori representation in the criminal

justice system along these lines, has been publicly available on the Statistics

New Zealand website for over 10 years. That data is rarely utilised in depth.

Key theme 4: The research record is sparse

Part of the problem with theorising about Maori offending is that the research

record is discontinuous – we never take one theory and thoroughly test,

enhance or re-examine it in light of new evidence. We just wait a few years for

another to come along – usually from overseas. Although the record may

seem broad it has little depth, and is actually small compared to other topics in

criminal justice.

Status quo

Notwithstanding the failure to account for Maori offence profiles, prevailing

opinion seems to be divided between those who see socio-economic

deprivation as key among numerous developmental and/or life course risk

factors (trajectory and risk theorists), and those who see it as stemming from

broad social inequalities (critical and counter-colonial criminologists). At

present, no one is joining the two together though the connection seems

obvious: colonisation generated broad social inequalities leading to

deprivation, the deprivation causes the crime, causes the inequality, causes

the deprivation.

Of course, all of this is of very little help (or interest, probably) to the victims

and offenders who find themselves caught up in the criminal justice system.

While we wait for existing theory to be enhanced in light of better data, and/or

for new theory to be developed, there is scope for using the data that we do

have to initiate primary crime prevention initiatives where they are most

needed. However, their efficacy rests on the assumption that much offending

is opportunistic, that is, it occurs on the spur of the moment without

premeditation or planning. The basic idea, famously demonstrated by Mayhew

et al., 1976), is that crime can be prevented by reducing opportunities for it to

occur, using techniques developed under the rubric of situational crime

prevention. Obviously, this does not address the underlying drivers of

offending. But this may not be necessary for the large majority of people

whose offending only occurs during adolescence.

According to the data, then, what characteristics of volume crime among

Māori are in most need of being addressed?

'New' data

In the most recent fiscal year, 2007/08, we know that 79% of all

apprehensions of Māori were of males (72,186 out of 91,944), in accordance

with the general rule that females are responsible for roughly 20% of reported

offences.

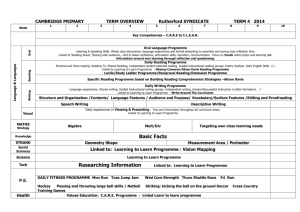

We can narrow the bulk of Maori apprehensions down to a relatively small

number of offence classes/types. It is important to note, however, that family

violence-related offending cuts across several different offence classes. When

collated (n=17,106), it exceeds all of the individual offence classes/types

noted above.

2007/08 Maori apprehensions, all ages, all genders, by key offence class/type (excl traffic)

17%

37%

6%

Assaults

Drugs (Cannabis Only)

Disorder

Burglary

Car Conversion Etc

11%

Theft Ex Shop (No Drugs)

Wilful Damage

Other

8%

8%

8%

5%

There are some variations on this theme when the data is broken down by

age/gender (excl family violence). For example, shoplifting accounts for 50%

of 0-9 year old Maori girls' apprehensions and 25% of 0-9 year old Maori boys'

apprehensions. "Disorder" and "assaults" tend to feature more prominently

from 17 years of age onwards, as access to alcohol increases.

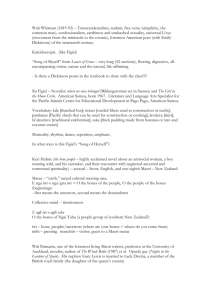

Police apprehensions of Māori males and females are disproportionately of

those aged between 14 and 30 years (see graph below). However, the age

profiles do vary by offence category (as well as class and type). Age

distributions of traffic apprehensions are slightly more skewed toward the

older age brackets, reflecting children and young peoples' relatively limited

access to vehicles.

Total Māori Apprehensions in 2007/08 (per 1,000 Māori) by Age Band

600

Māori Apprehensions per 1,000 Māori

500

400

Dishonesty

Drugs & AntiSocial

Violence

Property Damage

300

Property Abuse

Administrative

Sexual

Total

200

100

0

0 to 9

10 to 13

14 to 16

17 to 20

21 to 30

31 to 50

51 to 99

Age group

In 2007/08 (and preceding years), the Police areas with the highest volumes

of Maori apprehensions were: Hamilton city, Waitakere, Western Bay of

Plenty, Whangarei, Rotorua, Auckland city central, with some variations by

age and gender. Generally, the further south you go, the lower the volume of

Maori apprehensions.

On converting apprehension volumes into “crude” apprehension rates1 a more

classical picture is obtained. Auckland city has the highest rate of

apprehensions at 1,322 apprehensions per 1,000 Māori with Christchurch

central a distant second on 432 apprehensions per 1,000 Maori (the picture is

broadly the same irrespective of gender, though the extent of the problem is

worse for males). The conjecture is that the two rate hotspots are driven by

commuters rather than residents. The question then becomes: From how far a

field are these offenders travelling?

Over the past 10 years, diversions have remained fairly steady at 1-2% of all

resolutions. In 2007/08, Maori had the lowest proportion of cases resolved via

diversion at 0.6%, while "Asiatics" had the highest (5.9%) - suggesting a

possible model for good practice. Prosecutions have increased from 59% to

69% overall and warnings/cautions have dropped from 22% to 16%. 71% of

Maori (and "Pacific Isle") apprehensions are resolved by prosecution, 13% by

warnings/cautions. For "Caucasians", the corresponding figures are 66% and

18%. Ethnic discrepancies in offence resolutions between Maori and

"Caucasians" appear most pronounced among 14-16 yr olds.

1

Using 2006 census population data broken down by age, gender, ethnicity and Police area we can calculate a

"crude" rate by dividing the total number of apprehensions by the population figures and multiplying by (say) 1,000. It

is "crude" because it is assumes that each apprehension represents a discrete offender when we know that some

offenders are responsible for multiple apprehensions.

Road policing data is particularly important to Maori offence profiles because

"drink driving" is a driver of the Maori prison population. Ethnicity data is not

recorded in a lot of traffic-related apprehensions. But where we do have the

information, it reveals that drink driving dominates the four highest volume

offence types for Maori. This is more so for Maori females (45%) than males

(34%), and varies even more by age. Among Maori females aged 21-30, drink

driving comprises 76% of the apprehensions for the four key offence types. By

Police area, the highest volume of Maori traffic apprehensions were in the Far

North, Western Bay of Plenty, Whangarei, Rotorua, CM central, CM south,

Hamilton city, Gisborne, Hastings, Waitakere.

Making the most of available evidence

Most of us would have no difficulty in acknowledging the sources below as

evidence. Yet, despite the shortage of Maori-specific evidence on offer, we

rarely use all of these sources, let alone collectively.

6 monthly Maori apprehensions dataset (SNZ)

some analysis of NZCASS Maori findings (MoJ) available later in 2009,

and triennially at best

unpublished findings of TPK (assisted by MoJ, MWA, and Corrections)

engagement with Maori providers, practitioners & offenders (2007)

Moana Jackson’s colloquium (2008) and subsequent report (2009)

longitudinal studies (ongoing)

infrequent publications from Maori criminologists (Tauri, Webb, myself)

I think we could also agree that we need many more than this if we are to

address Maori offending. So, how do we generate more evidence?

Not by looking offshore to theory constructed without reference to the local

context. If we accept that all knowledge is socially constructed, and that what

makes one point of view acceptable at any one time is not that it is more

truthful than another but that it is backed by greater power resources, then I

believe we must look to popular culture as a source of evidence. The views of

very few people find expression in academic literature and policy circles. This

is especially true for Maori. According to the 1996 Adult Literacy survey, 70%

of Maori [45% of non-Maori] have literacy skills below what is regarded as the

minimum level required to meet the "complex demands of everyday life and

work" in the emerging "knowledge society". More perspectives are heard in

song lyrics, films, poetry, novels, biographies – the matatini performing arts

festival is a classic example of this. Great Maori composers like Tuini Ngawai

and her niece Ngoi Pewhairangi provided extensive commentary on a broad

range of social, political and cultural issues through the performing arts. And

their work was intimately linked with the Kotahitanga movement. I am not

suggesting uncritical acceptance of this material, but what Clifford Geertz

describes as analysis that searches for meaning, measured by the

consistency and coherence of “thick description”.

Responding to offending by Maori

There is no wonder drug for responding to Maori offending. Instead, there is a

choice we all need to make. We can stick with the status quo, tinker at the

fringes with ad hoc policy and research, jealously guarding our territory as

though we have a monopoly on expertise and competence. But theory not

based on robust evidence, which is what I propose we are relying too heavily

upon, is guesswork (no matter how well educated). And guesswork,

demonstrably, has a low probability of success.

Or, we can start afresh, and engage with ALL of the available evidence,

perhaps even invest in independent Maori research aligned to a proper

characterisation of "the problem". We can use it to tell us where, when, how

and with whom we need to make an impact if we are to reduce Maori

offending and victimization. And we can work with the people who are directly

affected by it, preferably while Maori offence profiles are relatively minor and

concentrated in few offence classes/types (i.e. before they reach the adult

jurisdiction), to develop solutions.

Whatever we do, unless it changes Maori criminal justice data, is ultimately

doomed. Why? Because corporate media are wedded to crime news. As long

as that crime news casts Maori in a consistently negative light, the discourse

surrounding Maori crime won’t change; therefore nor will Maori criminal

justice outcomes. As Foucault (cited in Davidson, 1997) famously said,

discourse is not merely a surface inscription. It brings about effects.

References

Alia, V. and Bull, S. (2005) Media and Ethnic Minorities. Edinburgh: Edinburgh

University Press.

Balzer, R., Haimona, D., Henare, M., and Matchitt, V. (1997) Māori Family

Violence in Aotearoa. Wellington: Te Puni Kokiri (TPK), the Ministry of

Māori Development.

Baudrillard, J. (1995) Simulacra and Simulation (translated by Sheila Glaser).

Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Braithwaite, J. (1989) Crime, Shame and Reintegration. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Bull, S. J. (2001) The land of murder, cannibalism, and all kinds of atrocious

crimes? An overview of "Māori crime" from pre-colonial times to the

present day, Victoria University of Wellington PhD thesis (Criminology).

Bull, S. (2004) The land of murder, cannibalism, and all kinds of atrocious

crimes? Māori and Crime in New Zealand, 1853-1919, British Journal

of Criminology, Vol. 44, No. 4, July 2004, pp. 496-519.

Bull, S. J. and Alia, V. (2004), ‘Unequalled Acts of Injustice? Pan-Indigenous

Encounters with Colonial School Systems’, Contemporary Justice

Review, Vol. 7, Issue 2, June, pp. 171-182.

de Bres, P. H. (1975) Māori Religious Affiliation in a City Suburb: The

Function of Urban Churches in Establishing Criteria for Social

Behaviour Among Immigrant Families. In: Kawharu, I. H. (ed.) (1975)

Conflict and Compromise: Essays on the Māori Since Colonisation.

Wellington: A. H. and A. W. Reed.

Davidson, A. I., ed. (1997) Foucault and his Interlocutors. London and

Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Department of Justice (1968) Crime in New Zealand. Wellington: R. E. Owen,

Government Printer.

Duff, A. (1990) Once Were Warriors. Auckland: Tandem Press.

Duncan, L. S. W. (1970) Crime by Polynesians in Auckland: An Analysis of

Charges Laid Against Persons Arrested in 1966. Master of Arts Thesis,

University of Auckland.

Duncan, L. S. W. (1971) Explanations for Polynesian Crime Rates in

Auckland. Recent Law, October 1971, pp. 283-288.

Durie, M. (2003) Imprisonment, Trapped Lifestyles, and Strategies for

Freedom. In: Ngā Kāhui Pou – Launching Māori Futures. Wellington:

Huia Publishers.

Fergusson, D. M., Donnell, A. and Slater, S. W. (1975) The Effects of Race

and Socio-Economic Status on Juvenile Offending Statistics. Research

Report No. 2. Wellington: Joint Committee on Young Offenders

(JCYO).

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., and Lynskey, M. T. (1993a) Ethnicity,

Social Background and Young Offending: A 14 Year Longitudinal

Study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, Vol. 26,

July, pp. 155-70.

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., and Lynskey, M. T. (1993b) Ethnicity and

Bias in Police Contact Statistics. Australian and New Zealand Journal

of Criminology, Vol. 26, December, pp. 193-206.

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., and Nagin, D. S. (2000) Offending

Trajectories in a New Zealand birth cohort, Criminology, Vol. 38, No. 2,

pp 525-551.

Fifield, J. and Donnell, A. (1980) Socio-Economic Status, Race, and Offending

in New Zealand. An Examination of Trends in Officially Collected

Statistics for the Māori and Non-Māori Populations. Research Report

No. 6. Wellington: Joint Committee on Young Offenders (JCYO).

Glover, M. (1993) Māori Women's Experience of Male Partner Violence:

Seven Case Studies. Master of Social Science Thesis, University of

Waikato.

Geertz, Clifford (1973) "Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of

Culture", in The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York:

Basic Books.

Hunn, J. K. (1961) Report on the Department of Māori Affairs. Wellington: R.

E. Owen, Government Printer.

Jackson, M. (1988) The Māori and the Criminal Justice System: He

Whaipaanga Hou - A New Perspective, Part 2. Wellington: Department

of Justice.

Lovell, R. and Norris, M. (1990) One in Four: Offending from Age Ten to

Twenty-four in a Cohort of New Zealand Males. Study of Social

Adjustment Research Report No. 8. Wellington: Department of Social

Welfare.

Lovell, R. and Stewart, A. (1983) Patterns of Juvenile Offending in New

Zealand: No. 1 Summary Statistics for 1978-1981. Wellington:

Department of Social Welfare.

Mayhew, P. M., Clarke, R. V., Sturman, A. and Hough, J. M. (1976) Crime as

Opportunity. Home Office Research Study No. 34. London: HMSO.

McCreary, J. R. (1955) Māori Age Groupings and Social Statistics. Journal of

the Polynesian Society, Vol. 64, No. 1, March, pp. 16-21.

McCreary, J. R. (1969) Consideration of Some Statistics on Māori Offending.

New Zealand Social Worker, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1969, pp. 40-45.

Morris, A. (1955) Some Aspects of Delinquency and Crime in New Zealand.

Journal of the Polynesian Society, Vol. 64, No. 1, March, pp. 5-15.

O'Malley, P. (1973a) The Amplification of Māori Crime: Cultural and Economic

Barriers to Equal Justice in New Zealand. Race, Vol. 15, No. 1, July,

pp. 47-57.

O'Malley, P. (1973b) The Influence of Cultural Factors on Māori Crime Rates.

In: Webb, S. D. and Collette, J. (eds.) (1973) New Zealand Society Contemporary Perspectives. Sydney: John Wiley and Sons Australasia

Pty Ltd.

Paterson, K. (1992) Wahine Maia, me te Ngawari Hoki - Māori Women and

Periodic Detention in Kirikiriroa: Their Life Difficulties and the System.

Master of Social Science Thesis, University of Waikato.

Philipp, E. (1946) Juvenile Delinquency in New Zealand - A Preliminary Study.

Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Rogers, H. (undated) A Study of Māori Crimes in Auckland. School of Social

Science Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington. Cited in Sheffield

(1958).

Sheffield, M. C. (1958) Māori Theft: A Study of Crime and Acculturation

Stress. Master of Arts Thesis, University of New Zealand.

Slater, S. W. and Jensen, J. (1966) Study of Crime Among Māoris. Interview

Study. Preliminary Report of Results. Joint Committee on Young

Offenders (JCYO). Unpublished report held at National Archives.

Smiler, W. (undated) Some Problems of Minority Groups. School of Social

Sciences Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington. Cited in Sheffield

(1958).

Stenning, p. (2005) Māori, Crime and Criminal Justice: Over-representation or

Under-representation?, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

(Victoria University of Wellington) Seminar, 18 March 2005.

Tauri, J. (2005). "Indigenous perspectives" In R. Walters & T. Bradley (Eds.),

Introduction to Criminological Thought: 129-145. Auckland: Pearson

Longman.

Webb, R. (undated) Social Change and Theorising on Māori Crime.

Association of Pacific Rim Universities Conference Presentation.

Unpublished.

Webb, R. (2003) Māori Crime: Possibilities and Limits of an Indigenous

Criminology, PhD thesis in Criminology, University of Auckland, New

Zealand.

Williams, C. (2001) The Too Hard Basket: Māori and Criminal Justice Since

1980. Wellington: Institute of Policy Studies, Victoria University of

Wellington.