Module 5 - CCH Group

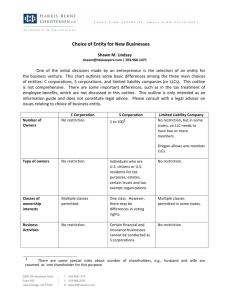

advertisement

Case 9 Converting a C Corporation into an LLC Introduction The issue of converting a C Corporation into a Limited Liability Company (LLC) is invariably related to the avoidance of double taxation that is present in a C Corporation. The C Corporation is a separate legal and taxable entity, with tax rates ranging from 15% to 35%. Once the income is earned by the C Corporation, the corporate level tax is applied. Then, as profits are distributed to shareholders, the profits are taxed once again as dividend income. This double taxation is avoided if the entity operates as an LLC, since this entity is generally taxed as a partnership. There is no entity-level tax for the partnership; rather, entity income simply flows through to the owners and retains its character. In the early years of life, a closely-held business may be able to more or less “zero out” the first-level corporate level income tax through deductible salary compensation to the owner/employees. This is particularly true in a service-oriented business that requires a relatively small capital investment. But as the business grows and the number of owners grows with it, it becomes increasingly difficult to eliminate significant amounts of C corporation taxable income through deductible payments to the owner-employees, and this is where the LLC option begins to look attractive. When the owners of an entity elect to convert from C corporation status to an LLC, Sec. 336 and Sec. 331, respectively, require a “deemed liquidation” of the corporation, followed by a “deemed liquidating distribution” of the net proceeds from the deemed asset sales to the shareholders. There may not be an actual liquidation, since many states now allow a conversion by simply filing a few forms and paying a fee. Nonetheless, there is the real dollar effect of double taxation at the point of conversion, and even though the “new” LLC entity will have stepped-up adjusted bases in the “contributed properties” to fair market values, the present costs of the deemed liquidation and distribution may far outweigh any future tax benefits from higher tax bases and the elimination of the double taxation issue. Conversion to an S corporation would avoid the deemed liquidation rules, but limits on the number and type of 1 shareholders, as well as the specter of special taxes such as the built-in gains tax and passive income tax, may make such an election impractical. The Limited Liability Company as a Tax Entity Prior to the enactment of the first LLC statutes, the choice of entity for most businesses boiled down to a difficult choice: the advantage of a single layer of tax afforded by a partnership (but at a cost of potential personal exposure to liability) versus the safe harbor from personal liability of a C corporation (but at the cost of the double taxation dilemma). Small family businesses would often choose a third option, the S corporation, but the relatively severe restrictions on ownership hampered growth opportunities when additional capital was needed. In 1977, Wyoming ushered in a new era in entity choice with the first LLC statute, which was in reality special-interest legislation for a specific mineral company. The statute was unique for U.S. tax purposes, in that the business entity was afforded limited liability protection (although an LLC member would still have unlimited liability due to professional negligence), and yet was structured under state law to be taxed as a partnership for federal income tax purposes. By 1990, only Florida had joined Wyoming in offering such an entity choice. Florida eventually reaped significant financial rewards due to increased business activity with this statute, and other states soon joined the parade. Today, every state offers some type of limited liability entity legislation which offers the same two advantages of the original Wyoming statute: limited liability and a single layer of federal income taxation through compliance with the partnership tax rules. This is both a blessing and a curse, as each state statute has its own peculiarities, and businesses that operate in a number of states must insure that each state entity complies with that state’s statute. For federal tax purposes, the state statutes are worded in a manner so that limited liability partnerships (LLPs) and limited liability companies (LLCs) are taxed as partnerships. Thus, each member of an LLC or LLP (members being the operative term for entity owners) picks up his or her share of the income, loss, and credits of the business entity. The profits are taxed as they are earned, not as they are distributed. Such income shares increase each owner’s tax basis in the LLC, and this in turn means that distributions to owners are generally tax-free reductions of basis. Members are taxed only on distributions of cash that exceed the member’s adjusted basis in the membership interest. LLC entities offer the same single layer of tax advantage when the business entity liquidates. The sale of business assets and subsequent distribution of the proceeds to the member in return for his or her membership interest is a taxable event, and generally this gain or loss is capital in nature. The gain on the LLC assets sales flows through to the members and is taxable. This recognized gain in turn increases the adjusted basis of the member’s interest in the LLC, so that when the cash is eventually received from the LLC 2 in return for the member’s interest, further gain is not recognized. Thus, there is no double taxation at liquidation of the LLC. The same result occurs if the assets are distributed directly to the member; gain or loss is measured by the difference between the fair market value of the assets distributed and the basis of the member’s interest. In the latter case, some of the gain may be ordinary income under the “hot asset” rules of Sec. 751 applicable to certain unrealized receivables and inventory. This liquidation result with an LLC should be contrasted with the liquidation of a C Corporation. When a C Corporation liquidates, an actual sale of the corporate assets creates a taxable gain to be recognized by the C corporate entity. And when the net cash received is distributed to the shareholders in return for their stock, a second round of taxation occurs. This double taxation cannot be avoided by simply distributing the corporate assets directly to the shareholders; Sec. 336 requires a hypothetical “deemed sale” of the assets that must be reported by the C Corporation as though all corporate assets were sold for their fair market values. As discussed below, this is a critical factor when considering a conversion from the C Corporation to an LLC. Motivations for Converting a C Corporation to an LLC There are a number of tax-related motivating factors for converting a business (particularly a closely-held business) from a C Corporation to an LLC. This is especially true during the current economic downturn, where asset values are lower and at a time Congress is considering increases in tax rates. Among the primary motivating factors are: Eliminating Double Taxation – Eliminating the second tax on distributions to business owners is obviously one of the primary motivators for C to LLC conversions, especially for companies that are growing so fast that deductible reasonable salary cannot keep pace with corporate income. As a result, the retained income builds and will be taxed a second time when distributed, either as a regular dividend or as a liquidating distribution when business ceases. Lower Assets Values During the Current Economic Downturn – The near collapse of the economy in the last two years has forced down property values to near historic lows. This in turn decreases the gain recognized on the hypothetical “deemed sale” of corporate assets (described below) when converting to an LLC. As the economy recovers, the increased asset values mean more of a double tax surcharge if conversion is elected. If the deemed distribution actually results in a loss to the shareholders (i.e., the deemed cash available for distribution is less than the shareholder’s basis), can such loss be recognized? The answer appears to be yes; for example, in Ltr. Rul. 200214016, the IRS ruled that conversion of a corporation to an LLC pursuant to a state law merger would trigger any tax loss in the stock held by the investors. And if the stock qualified as Sec. 1244 stock, the first $50,000 ($100,000 married filing jointly) would be ordinary 3 loss, and not capital loss. Thus, in some cases, the deemed distribution rules may actually be an incentive for making the conversion. Unused Net Operating Losses and Capital Losses – The current economic downturn may also lead to large unused net operating loss and capital loss carryovers. Normally, these losses are trapped in the C Corporation until such time the company once again turns profitable, or generates capital gains in the case of capital loss carryovers. As explained below, these carryovers may be used to offset any deemed liquidation gain on conversion. This factor may significantly reduce the costs of conversion. The Specter of Higher Tax Rates – There is little question that tax rates on middle- and high-income individuals will be increasing soon, and if the conversion is delayed, the double taxation effects of the “deemed sale” upon conversion will be even larger. And even though some of the gain on the deemed sale may be taxed as capital gain, the 15% alternative capital gains rate is scheduled to revert back to 20% after 2010. The Elimination of the Preferential Tax Rate for Corporate Dividends – Unless Congress acts in the interim (which given the current budget shortfalls is highly unlikely), the 15% special rate for corporate dividends is scheduled to expire after 2010. After that time, dividends will be taxed at ordinary income, up to the maximum individual rate (currently 35%, but likely to go up as well). So now may be the time to eliminate the C corporation double-taxation problem, before the preferential dividend treatment expires. Possible Negative Consequences of a C to LLC Conversion There are several possible negative consequences of a C to LLC conversion, some obvious and some not so obvious. Among the negative factors are the following: Deemed Distribution Rules – The deemed distribution rules are perhaps the biggest deterrent to a C Corporation conversion to an LLC. Although state law may not require an actual liquidation, Sec. 336 of the Internal Revenue Code treats such a conversion as a “deemed liquidation” of the C corporation, which means that the corporation must pay income tax on the excess of the fair market value of the corporate assets over their adjusted bases. Then such hypothetical cash proceeds (after reduction for the deemed income taxes on the hypothetical sale and other liabilities of the corporation) are deemed to be distributed to the C Corporation shareholders in return for liquidating their stock investments. Thus, the deemed liquidation results in taxation at the corporate level, and then again at the shareholder level. Several factors may serve to limit the tax consequences of the deemed liquidation. First, since taxes are paid on the unrealized gains, the adjusted basis of all corporate assets is increased by the gains recognized, i.e., the new adjusted basis of each asset is its fair market value. Additionally, foreign corporations may be able to convert to LLC without much tax incidence, if they do not have effectively connected U.S. income. And finally, there is one common C to LLC conversion that does not result in a taxable 4 deemed liquidation: the conversion of an 80%-controlled subsidiary to an LLC by its parent. Sec. 332 specifically eliminates any taxable gain on such a liquidation of a subsidiary; instead, the adjusted bases of the subsidiary’s assets simply carryover to the LLC. These conversions are often made to avoid state franchise taxes. Self-Employment Tax Issue – The LLC equivalent of a general partner under partnership law will be subject to self-employment taxes. This person is the LLC member who materially participates in the day to day activities of the LLC. Furthermore, any other LLC members who participate in the business may fall under the self-employment tax rules as well. It is true that employees of the C Corporation will pay employment taxes that are matched by the corporation, so in some cases the effects of this issue are minor. However, one point needs to be noted; an LLC member who is subject to the selfemployment tax will pay payroll taxes on any guaranteed payments plus his or her full share of the “ordinary income” of the LLC. This may be larger than the equivalent salary of the same individual in the C Corporation entity format. Example – During the current year, the LLC Company had $500,000 of ordinary income before deducting a $200,000 salary to its managing member Susan, a 40% owner in the business. On Susan’s Form 1040, she will be pay the self-employment tax on her $200,000 guaranteed payment plus her income share of $120,000 [($500,000 ordinary LLC income - $200,000 guaranteed payment) x .40 share]. If the entity were a regular corporation, Susan and the corporation would pay employment taxes only on her $200,000 salary. Deemed Goodwill in Service Businesses – Service businesses tend to be less capital intensive than retailers and producers, so the tax on the deemed liquidation may not be a deal breaker in such a case. On the other hand, it is possible that significant goodwill could attach to such a business for a variety of reasons. Thus, a business that has assets valued at $800,000 may actually be worth $1,200,000 when appraised because of the existence of such goodwill. Evaluating the Tax Costs and Benefits of Conversion Any model designed to evaluate a conversion must incorporate fully all present costs of the “deemed liquidation” of the C corporation. In effect, it is assumed that all corporate assets are sold at their fair market values, and any resulting hypothetical gain/loss is recognized by the C Corporation on its final tax return. If the C Corporation has any unused net operating loss or capital loss carryovers, these amounts may offset the deemed liquidation gain. Liquidation of the C corporation also involves a “deemed distribution” from the corporation to the shareholders of the net cash received from selling the assets. In effect, this is a hypothetical liquidating distribution, and each shareholder must recognize gain or loss equal to the difference between his or her share of the cash proceeds (after reduction for taxes on the deemed liquidation and other liabilities) and his or her adjusted basis in 5 the stock interest. Thus, the hypothetical liquidation involves a final round of double taxation before leaving the C Corporation entity, and this present cost must be built into any model that evaluates the conversion decision. Finally, there is one other possible cost associated with the conversion: the present value of potential additional payroll taxes when operating as an LLC. Recall that some LLC members have higher ordinary income and guarantee payment shares than the equivalent amount of salary the members received in a C Corporation. The potential costs associated with this factor depend on the number of shareholder employees and their related salaries, and in many cases the differences may be insignificant. Nonetheless, this factor may increase total costs of conversion and should be considered in such comparisons. On the tax benefits side, any model analyzing the conversion decision must make some type of projections of the present value of future tax savings of the new LLC caused by the avoidance of a second layer of taxation. This would necessarily involve estimating both deductible salaries and the nondeductible dividends that would otherwise be paid in the future if the conversion was not made. There is one final benefit factor that should be included in the model; the possible effects of a final liquidation of the business entity. Most businesses considering a conversion will discount this factor under the theory that the entity will “be in business forever” and need not worry about a final reckoning in the immediate future. However, it is important to realize that if the conversion is not made, the same double taxation process eventually occurs when the C Corporation is finally liquidated. But if the conversion decision was made, there would only be a single layer of taxation to the LLC. The tax effects of this factor are also magnified by the fact that the adjusted bases of the entity assets on the LLC liquidation would be higher due to the deemed gains recognized on the original conversion. The adjusted bases of the C Corporation assets would still be the original costs. So these differential tax savings should also be considered, even though final liquidation may be many years in the future. Case Study: Facts BALD Corporation is a closely-held family C Corporation with four shareholders: Al Allen (40%), Beth Braxton (30%), Cheryl Cooper (20%), and Dan Dancer (10%). Al and Beth are full-time shareholder-employees of BALD Corporation, and Cheryl and Dan are investors only. Sixty percent of the annual net income of the company is paid out in salaries to Al and Beth each year (in a 60:40 ratio, respectively), and the remaining income each year is distributed as dividends to the four owners based on each shareholder’s stock ownership percentage. All shareholders have a 35% marginal federal tax rate with the exception of Dan, who has a 28% marginal tax rate. The adjusted bases of each shareholder’s stock holdings in BALD Corporation are $1,200,000 (Al), $900,000 (Beth), $600,000 (Cheryl), and $300,000 (Dan). 6 The current-year taxable income (before considering salary deductions) is $300,000, and this amount is expected to increase 15% per year in the future, and salary payments to Al and Beth are expected to increase at the same 15% rate. The after-tax discount rate to use for time-value of money considerations is 5%, and the FICA social security wage base is expected to increase at a 3% annual rate in the future. BALD Corporation was formed exactly five years ago, with the following assets, shown at their original costs, along with the actual appreciation or depreciation rates for each asset during the past five years and the projected appreciation or depreciation rates for the next ten years, respectively: Original Corporate Assets at Formation of C Corp Cash Accounts receivable Marketable securities Inventory (LCM) Equipment A (7-year S/L MACRS) Equipment B (7-year S/L MACRS) Office furniture (7-year S/L MACRS) Office building (39-year MACRS) Land Goodwill Cost 130,000 298,000 82,000 388,000 700,000 620,000 210,000 1,650,000 954,000 0 App (Depr) Rate up to Conversion (5 Prior yrs) 0.00 0.00 0.02 0.01 (0.05) (0.05) (0.05) 0.01 0.01 0.00 App (Depr) Rate After Conversion (Next 10 yrs) 0.00 0.00 0.02 0.01 (0.05) (0.05) (0.05) 0.01 0.01 0.00 The only liabilities of BALD Corporation are a $908,000 mortgage on the building and land, and $104,000 of accounts payables. As of the end of the current year (the fifth year of operations), BALD has no net operating loss or capital loss carryovers. There is no existing goodwill related to the corporate entity. BALD Corporation is considering an immediate conversion to an LLC under state law, and asks for a comprehensive analysis of the expected tax benefits and costs of such conversion, assuming that BALD will operate as an LLC for a minimum of ten years before a final liquidation. Such an analysis will include computations of (1) estimated present tax costs of the deemed sale of BALD Corporation assets, (2) estimated present tax costs of the deemed liquidating distributions of the net proceeds of such sales (after payment of income taxes and company liabilities) to BALD shareholders, (3) estimated costs of any additional future payroll taxes caused by the conversion to an LLC, and (4) estimated future tax savings generated by elimination of the double taxation of dividend payments. BALD also requests a separate estimate of the future tax savings if the new LLC is actually liquidated ten years after the conversion to an LLC as opposed to continuation as a C corporation and liquidating the entity at the same time. Use the Case 9 – LLC Conversions – 2013 spreadsheet. 7 The Spreadsheet Evaluation Tool (Use the Case 9 – LLC Conversions – 2013 spreadsheet) Input Features: The initial inputs on Sheet 1 of the spreadsheet specify certain economic assumptions, appreciation and depreciation rates, and planning horizons for purposes of projecting future results. The original assets of the C corporation at formation are listed, and the appreciation (depreciation) rates are given for two time periods: (1) actual rates from formation up until the date of conversion, and (2) projected rates from the date of conversion until a presumed final liquidation of the entity. Shareholder/member characteristics are provided for up to four owners of the entity, including any deductible salary payments to member/employees. An assumption is made that any salary payments are considered to be FICA wages for federal payroll tax purposes. Output Features: The second table on Page 2 of Sheet 1 summarizes the estimated costs and (savings) from converting the C corporation entity to an LLC. All supporting computations are shown in other sheets of the spreadsheet. The second page of the spreadsheet (Sheet 2) summarizes the computed adjusted bases and estimated fair market values of company assets (1) at conversion (based on the number of years after formation of the entity) and (2) at the presumed final date of liquidating the entity (based on the related input time horizon). The third page of the spreadsheet (Sheet 3) discloses the payroll tax liability differentials due to conversion. Only Year 1 and Year 2 computations of these differentials are included in Appendix A. 8 Case 9 Converting a C Corporation into an LLC 1. Based on the current output in the spreadsheet, would BALD Corporation be likely to convert to LLC based on tax savings generated by the elimination of the double taxation issue? Explain, mentioning the key factors driving the result. 2. Complete the following projected table of results by varying the input values listed in the first three columns. Note that all other variables remain the same, and that the 15% maximum dividends tax rate will apply in the future. Table 1 Sensitivity Analysis Present Value of Net Tax Costs (Savings) Conversion of C Corporation to a Limited Liability Company (Assuming the Current 15% Rate on Dividend Income) Present Value of Net Tax Costs Changes in Selected Input Variables (Savings) at Conversion and With a Final Liquidation Salaries as App (Depr) App (Depr) Cost (Savings) Cost (Savings) a Pct. of Rates on All Rates on All With Conversion With Final Income Machinery Build/Land Only Liquidation 60% 60% 60% 60% 40% 40% 40% 40% 80% 80% 80% 80% ( 5%) ( 5%) (10%) (10%) ( 5%) ( 5%) (10%) (10%) ( 5%) ( 5%) (10%) (10%) 1% 3% 1% 3% 1% 3% 1% 3% 1% 3% 1% 3% Comment on any significant trends that this sensitivity analysis reveals. 9 3. Complete the following projected table of results by varying the input values listed in the first three columns. Note that all other variables remain the same, and that an assumption is made that the 15% maximum dividends tax rate is repealed. Table 2 Sensitivity Analysis Present Value of Net Tax Costs (Savings) Conversion of C Corporation to a Limited Liability Company (Assuming Ordinary Income Treatment of Dividend Income) Present Value of Net Tax Costs Changes in Selected Input Variables (Savings) at Conversion and With a Final Liquidation Salaries as App (Depr) App (Depr) Cost (Savings) Cost (Savings) a Pct. of Rates on All Rates on All With Conversion With Final Income Machinery Build/Land Only Liquidation 60% ( 5%) 1% 60% ( 5%) 3% 60% (10%) 1% 60% (10%) 3% 40% ( 5%) 1% 40% ( 5%) 3% 40% (10%) 1% 40% (10%) 3% 80% ( 5%) 1% 80% ( 5%) 3% 80% (10%) 1% 80% (10%) 3% Comment on any significant trends that this sensitivity analysis reveals. 4. In the examples thus far, an assumption was made that no goodwill existed in BALD Corporation at the time of the conversion. Assume that an objective evaluation of the company indicates that goodwill does exist, primarily due to the personal efforts and technical knowledge of the Al Allen, one of the shareholderemployees of the company. Could BALD Corporation make the argument that the goodwill attaches solely to his unique efforts, and therefore should not be assigned to the company? Research this issue, and explain your conclusions. (Hint – research corporate liquidations and related goodwill issues.) 10 5. Assume that BALD Corporation is a Virginia C corporation and decides to make the conversion. What steps will they have to take to effect such a conversion? What is the key state form (or forms) needed to make the election? (Hint – research the statutes of the State Corporation Commission of Virginia.)

![Your_Solutions_LLC_-_New_Business3[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005544494_1-444a738d95c4d66d28ef7ef4e25c86f0-300x300.png)