Paedagogica Historica

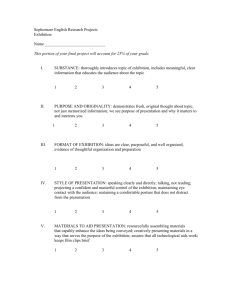

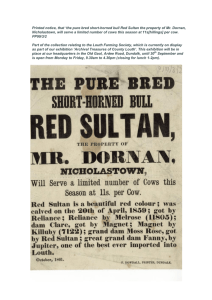

advertisement