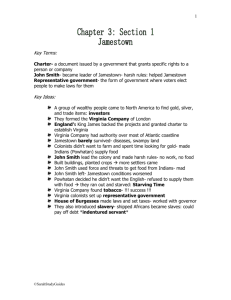

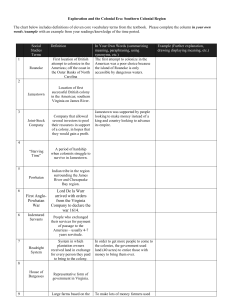

Jamestown: Background Information

advertisement

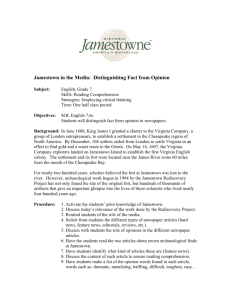

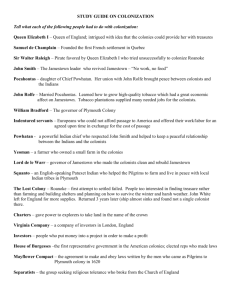

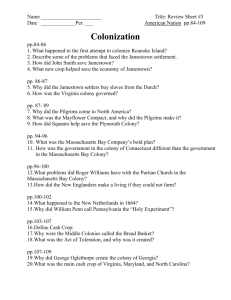

Jamestown: Background Information Former village, SE Virginia, first permanent English settlement in America; established May 14, 1607, by the London Company on a marshy peninsula (now an island) in the James River and named for the reigning English monarch, James I. Disease, starvation, and Native American attacks wiped out most of the colony, but the London Company continually sent more men and supplies, and John Smith briefly provided efficient leadership (he returned to England in 1609 for treatment of an injury). After the severe winter of 1609-10 (the starving time), the survivors prepared to return to England but were stopped by the timely arrival of Lord De la Warr with supplies. John Rolfe cultivated the first tobacco there in 1612, introducing a successful source of livelihood; in 1614 he assured peace with the local Native Americans by marrying Pocahontas, daughter of chief Powhatan. In 1619, the first representative government in the New World met at Jamestown, which remained the capital of Virginia throughout the 17th cent. The village was almost entirely destroyed during Bacon's Rebellion; it was partially rebuilt but fell into decay with the removal of the capital to Williamsburg (1698-1700). Of the 17th-century settlement, only the old church tower (built c.1639) and a few gravestones were visible when National Park Service excavations began in 1934. Today, most of Jamestown Island is owned by the U.S. government and is included in Colonial National Historical Park (see National Parks and Monuments, table); a small portion comprises the Jamestown National Historic Site, which is owned by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. A tercentenary celebration was held in 1907, and in 1957 the Jamestown Festival Park was built to commemorate the 350th anniversary. The park contains exhibit pavilions and replicas of the first fort, the three ships that brought the first settlers, and a Native American lodge. London Company London Company, corporation composed of stockholders residing in and about London, which, together with the Plymouth Company (see Virginia Company), was granted (1606) a charter by King James I to found colonies in America. The London Company was granted a tract of land fronting 100 miles (160 km) on the sea and extending 100 miles inland, somewhere between lat. 34°N and lat. 41°N. Government was vested in an English council, appointed by the king, which was to appoint a local council for the colony. The company's expedition, under the command of Capt. Christopher Newport, founded (1607) Jamestown in Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in America. In May, 1609, the company received a new charter, extending its territory and enabling it to replace the local council with an absolute governor. Thomas West, Baron De la Warr, was the first to hold that office, with Sir Thomas Gates as his deputy. A third charter, granted in March, 1612, made the London Company a self-governing body. There was, however, dissension within the company over governing policies, and the governing council was soon divided into two parties. The court party, headed by Sir Robert Rich (later the 2d earl of Warwick) and Sir Thomas Smythe, favored prolongation of martial law in the colony. The country, or patriot, party, led by Sir Edwin Sandys, Sir John Danvers, and John and Nicholas Ferrar, favored discontinuance of the system of servitude. The country party was in the majority, but a liberal form of government was not established until after the appointment of Sir George Yeardley as governor of Virginia. Yeardley convened America's first legislative assembly at Jamestown in 1619. Although affairs in Virginia gradually improved, a petition was presented (1623) to the king calling for an investigation of conditions in the colony. Shortly afterward there appeared a paper, The Unmasked Face of Our Colony in Virginia. Already offended by the company, the king now took extreme measures. A report was made by an investigating commission, the case was tried before the King's Bench, and the unfavorable decision, rendered in May, 1624, resulted in the dissolution of the company. About £200,000 had been expended by the company and more than 10,000 emigrants sent to Virginia. POCAHONTAS c. 1596-1617, Indian "princess." Reputedly the favorite daughter of the Algonquin chief Powhatan, Pocahontas contributed significantly to the early survival of the Jamestown colony and played a brief but dramatic role in English imperial propaganda. Her untimely death cut short her successful mediation between the Powhatan Indians and the colony. Both before her intercession and long after her death, Jamestown -the first permanent English outpost in North America - was precarious, largely because of Indian hostility to the colony and its expansion. Pocahontas's contributions to Jamestown date from her early acquaintance with Capt. John Smith after his capture by Powhatan's men in 1607. Her legendary rescue of the English captain on the verge of his execution was probably part of a traditional Indian adoption ceremony (misinterpreted or misunderstood by Smith), though it is possible that without her intercession he would have been killed. In any event, relations between Powhatan and the fledgling colony improved, and Pocahontas, then about twelve years old, became a frequent visitor at Jamestown and an important supplier of food for the colonists. She also became an informer for the colony, warning Smith of her father's belligerent plans. After Smith's return to England, Pocahontas disappears for several years from the historical record. She may have married an Indian, resumed her proper name of Matoaka ("Pocahontas" was a nickname), and shunned the English, who, under Sir Thomas Dale, were at war with Powhatan. To force Powhatan's submission, Capt. Samuel Argall in 1613 lured Pocahontas on board a ship and held her hostage. During a prolonged captivity, she was converted to Christianity by the Reverend Alexander Whitaker and baptized as "Rebecca." In 1614 she married John Rolfe, a prominent colonist and recent widower. Powhatan grudgingly agreed to a truce with the colony that lasted until 1622. The Virginia Company of London quickly recognized Pocahontas's enormous propaganda value as an example of Anglo-Indian harmony, of missionary success among the natives, and of the prospect that Indians could be persuaded to adopt English ways. To attract new settlers and fresh investments, the company in 1616 brought the Rolfes, their son, Thomas (b. 1615), and an entourage of a dozen or so Indians to England. She met many of the era's major figures, was presented at court, and had her portrait painted. She also took ill, probably from diseases that had no American counterpart. Pocahontas died in March 1617, after boarding ship for a return to Virginia, and was buried in Gravesend, England. With the death of Pocahontas and, soon after, of Powhatan, the fragile peace between colonists and Indians eroded. Ironically, the Indians' major grievance was the colonists' insatiable demand for land, triggered principally by windfall profits from the tobacco species introduced by John Rolfe. In the public mind, Pocahontas is linked especially, and often romantically, with Smith. The rescue episode did not appear in Smith's accounts of Virginia published in 1608 and 1612 but surfaced in his Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles (1624). Doubts have been cast ever since on its authenticity and, if true, its meaning. Ethnographers and historians now generally agree that the event could well have taken place and that Smith's reasons for suppressing the story until 1624 had more to do with Pocahontas's early obscurity than with literary invention. CHESAPEAKE COLONIES In the middle of the seventeenth century, a resident complained that the Chesapeake "is reported to be an unhealthy place, a nest of Rogues, whores, desolate and rooking persons; a place of intolerable labour, bad usage and hard Diet." Such circumstances, partly true of early Virginia, were an inauspicious beginning for England's first region of permanent settlement on the North American mainland and a misleading harbinger of the Chesapeake's eighteenthcentury prominence and prosperity. English interest in the Chesapeake area had begun in the late sixteenth century as a prospective outpost for attacking Spanish ships, as a possible source of precious metals and semitropical crops, as a presumably congenial location for English settlement and conversion of the Indians, and, perhaps, as the eastern terminus of a transcontinental passage. By the early seventeenth century, when English explorations farther north and south proved disappointing, England's imperialists focused on the Chesapeake area as the most promising site for British colonization. The formation of the Virginia Company of London in 1606 led the following year to England's outpost at Jamestown and eventually to the extensive settlement of Virginia and Maryland. Although the Jamestown colony survived, it failed for several decades to accomplish any of its avowed objectives. The outpost, moreover, was lethal to its settlers, expensive to its investors, and intermittently at war with its native neighbors. Major problems were the colonists' lack of appropriate skills and the company's inability to send necessary supplies. As a garrison against attacks and simultaneously a self-supporting work force, the first colonists should have been predominantly soldiers, farmers, and laborers. Instead, they were a hodgepodge of workers with irrelevant skills and posturing lesser gentry. Matters improved only slightly with additional recruits and supplies. Time and again, the wrong people and wrong things arrived. As England's first major experiment in American colonization, the Chesapeake was a trial-and-error disaster. The mortality rate in the early years reflects the colony's problems. From an initial population of approximately 105 at its founding in 1607, the number dropped to 50 at the end of the first year; new arrivals swelled the ranks to nearly 400 by the summer of 1609, but a year later the number was down to 90. A few settlers had returned to England, but most of the population loss came from persistent diseases and Indian retaliation for encroachment and forced contributions of food. The deadly pattern continued well into the 1620s and abated only gradually thereafter. Even after 1624, when Virginia came under direct Crown control and Maryland (settled in the 1630s) was administered by a benign proprietor, the Chesapeake compared poorly in healthfulness, orderliness, and overall prosperity to New England and, in some respects, to the British Caribbean. Maryland, founded a generation after Jamestown, learned from Virginia's mistakes. Lord Baltimore's colony began with more realistic expectations and better planning and accordingly enjoyed relative health and tranquillity in its early years. It also attracted a more dedicated group of colonists. As a haven for Roman Catholics (though they were a minority in the colony from the outset), Maryland appealed to families with intentions of staying the course rather than to single men with expectations of quick profits and an early departure. But Maryland's golden age was brief; as Virginia gradually gained stability, Maryland succumbed to internecine strife. For most of the seventeenth century, the two British colonies suffered internal friction and hostility not only with neighboring Indians but often with each other. The Chesapeake's economic vitality began with John Rolfe's introduction of a superior species of tobacco from Trinidad in 1612. The imported plants (Nicotiana tabacum) flourished in the Tidewater's soil and climate; soon a tobacco craze hit Virginia that undermined efforts to grow other crops, even for local use. The early settlers of Maryland followed suit. By mid-century, the Chesapeake colonies were exporting large and profitable tobacco cargoes and their prosperity thereafter rose and fell with fluctuations in the international market. Tobacco profits dramatically increased the demand for labor. When early hopes that the Indians would work for the English proved ephemeral, a system of indentured labor (whereby one worked usually for four or five years in exchange for passage to America and all necessities during the period of service) was linked to head rights of fifty acres of land (sometimes one hundred acres in Maryland) to anyone who paid a person's passage to the colony. This system provided a temporary solution to the labor shortage; it also encouraged the amassing of huge estates by men rich enough to obtain scores of head rights. But, the number of indentured immigrants was always inadequate, and the ex-servants often became tobacco growers themselves, thus increasing the demand for servants. And, as good farming land became scarce, the ex-servants increasingly formed a disgruntled frontier subculture - landless, restless, and armed - that culminated in Nathaniel Bacon's uprising in 1676 in Virginia. Moreover, the demand for field-workers skewed the sex ratio heavily toward male immigrants, which gave the Chesapeake a heavy (about five to one) male preponderance during most of the seventeenth century. Indentured servants remained an important part of the Chesapeake labor force throughout the colonial era, but by the late seventeenth century they were no longer its core. In the eighteenth century, Maryland imported substantial numbers of British convicts as bound laborers, usually with terms of seven years, but again the supply fell short of the need. Slavery was the solution. In both Virginia and Maryland, the shift to imported African slave labor began early but did not reach major proportions until the last quarter of the seventeenth century, when a growing demand for labor coincided with a slackening of the supply from England and an expansion of the Atlantic slave trade. By the second quarter of the eighteenth century, black labor predominated, although white workers continued to hold most of the skilled positions on the tobacco plantations until acculturated slaves took over those roles as well. Whites of all socioeconomic classes increasingly eschewed labor in the fields, as a caste system based on pigmentation became a hallmark of Chesapeake society. By the eve of the American Revolution, African-Americans constituted nearly 40 percent of the region's non-Indian population. In both Virginia and Maryland, leadership in the eighteenth century came from the planters and their associates - merchants and lawyers - though the roles often overlapped. The plantocracy dominated both houses of the legislatures, the local governments, the colonial militias, and the church vestries. A few families, most notably in Virginia, set the tone for a society that emulated the English landed gentry's style and influence. But, unlike its English counterparts, the Chesapeake aristocracy depended on a single-crop economy based on vast landholdings and black bondsmen. Even toward the end of the eighteenth century, when falling tobacco prices and exhausted soil encouraged a more diversified economy, tobacco and slaves remained central to the colonial Chesapeake, and the plantocracy retained its remarkable homogeneity and hegemony. The power of the plantocracy took on new meaning in the 1760s and 1770s when the struggle with the mother country highlighted a remarkable cadre of articulate and energetic leaders whose national prominence lasted far beyond the revolutionary era. Jamestown Interactive Questions http://www.iath.virginia.edu/vcdh/jamestown 1. First take the “Walking Tour” of the website. Click on each of the images and read the summaries to familiarize yourself with what your are going to learn. Does this seem like an interesting cite? Is this a good way to learn history? 2. Click of the “Maps and Images” icon. Then select “a) Original Maps”. Look at each of the maps on the page. Are they different from the maps you see today? How are they different? Why do you think they put all those pictures on them? Do you believe these maps are accurate? Compare the maps to each other. How are they alike? How are they different? Notice who made them and when they were made. Does this make a difference in the quality of the maps? 3. In the “Maps and Images” section, click on the “c) Images” and “Jamestown Artifacts.” Look at each of the artifacts from Jamestown and read the descriptions of each one. What kinds of thoughts and images do these pictures give you of colonial life? Was it hard/easy? What kinds of things were important to the people? How did they live? 4. Click on the “Labor Contracts” and read the summary in blue. What is an indentured servant? Why would people put themselves into indentured servitude to get to America? Click on “b) contracts” and read the contract of Richard Lowther. If you have trouble understanding the Old English version, click on the “modern-spelling version.” How long did Richard Lowther have to serve Edward Hurd? What does Richard get in return for becoming an indentured servatude? 5. Click on “First Hand Accounts and Letters.” Then, click on “a) First Hand Accounts and Letters by Date.” Read at least five (5) letters and print them out. What do the letters say about colonial life? What is happening in the letters? Do they paint a positive picture of Native Americans? What kind of image do you get of the Native Americans from the letters?