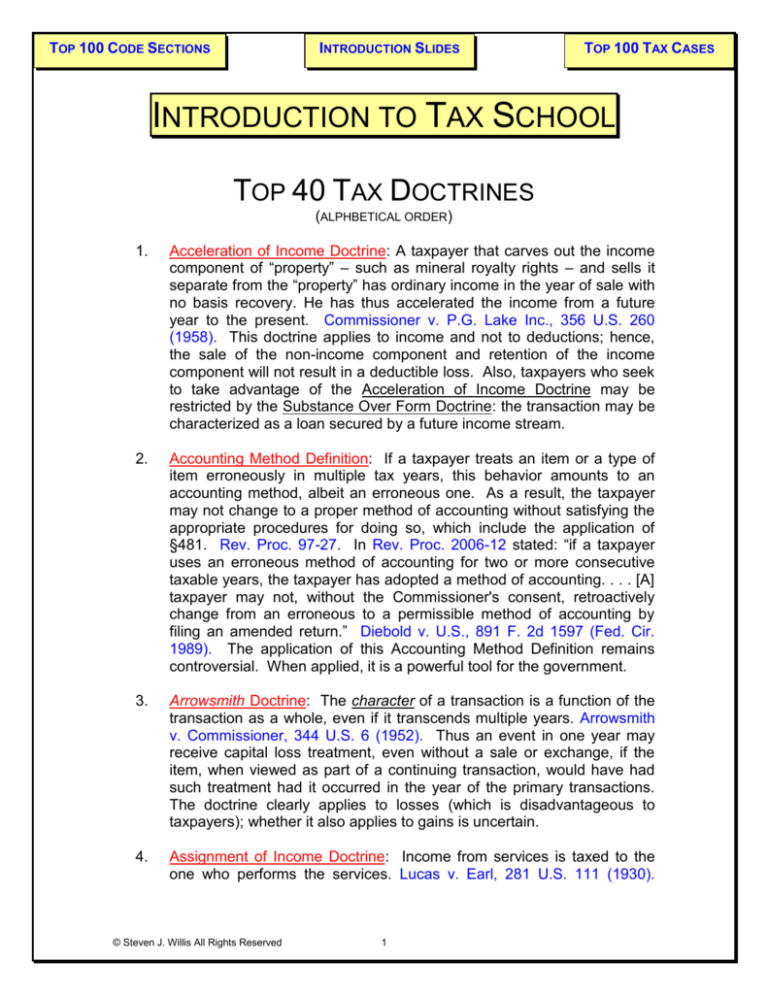

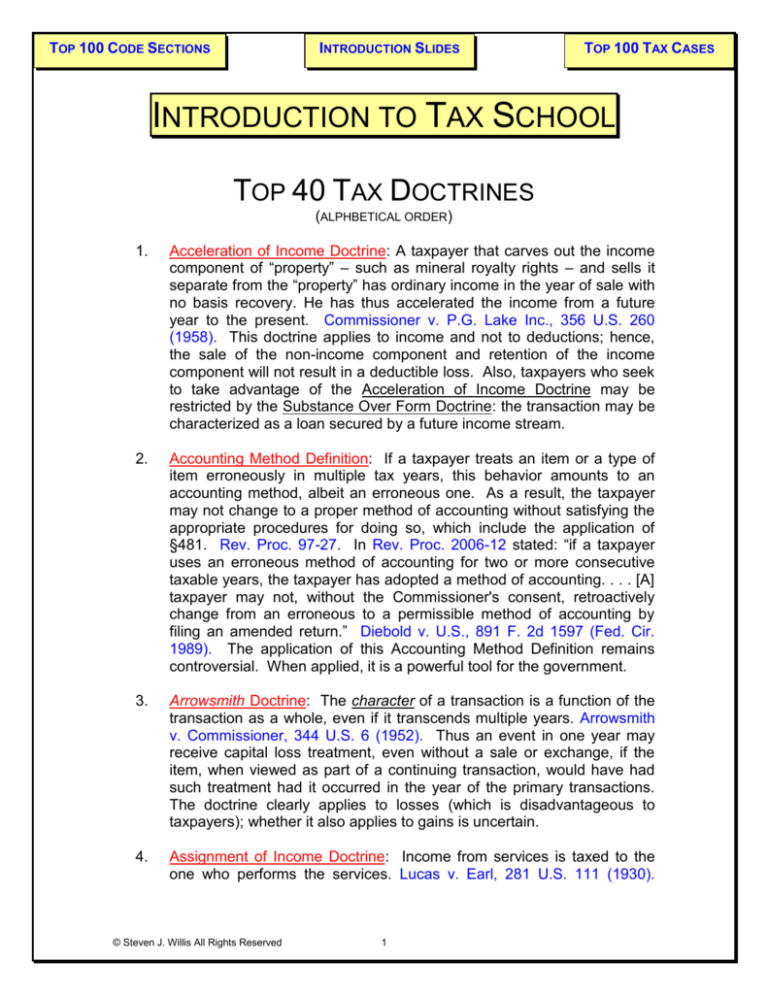

TOP 100 CODE SECTIONS

INTRODUCTION SLIDES

TOP 100 TAX CASES

INTRODUCTION TO TAX SCHOOL

TOP 40 TAX DOCTRINES

(ALPHBETICAL ORDER)

1.

Acceleration of Income Doctrine: A taxpayer that carves out the income

component of “property” – such as mineral royalty rights – and sells it

separate from the “property” has ordinary income in the year of sale with

no basis recovery. He has thus accelerated the income from a future

year to the present. Commissioner v. P.G. Lake Inc., 356 U.S. 260

(1958). This doctrine applies to income and not to deductions; hence,

the sale of the non-income component and retention of the income

component will not result in a deductible loss. Also, taxpayers who seek

to take advantage of the Acceleration of Income Doctrine may be

restricted by the Substance Over Form Doctrine: the transaction may be

characterized as a loan secured by a future income stream.

2.

Accounting Method Definition: If a taxpayer treats an item or a type of

item erroneously in multiple tax years, this behavior amounts to an

accounting method, albeit an erroneous one. As a result, the taxpayer

may not change to a proper method of accounting without satisfying the

appropriate procedures for doing so, which include the application of

§481. Rev. Proc. 97-27. In Rev. Proc. 2006-12 stated: “if a taxpayer

uses an erroneous method of accounting for two or more consecutive

taxable years, the taxpayer has adopted a method of accounting. . . . [A]

taxpayer may not, without the Commissioner's consent, retroactively

change from an erroneous to a permissible method of accounting by

filing an amended return.” Diebold v. U.S., 891 F. 2d 1597 (Fed. Cir.

1989). The application of this Accounting Method Definition remains

controversial. When applied, it is a powerful tool for the government.

3.

Arrowsmith Doctrine: The character of a transaction is a function of the

transaction as a whole, even if it transcends multiple years. Arrowsmith

v. Commissioner, 344 U.S. 6 (1952). Thus an event in one year may

receive capital loss treatment, even without a sale or exchange, if the

item, when viewed as part of a continuing transaction, would have had

such treatment had it occurred in the year of the primary transactions.

The doctrine clearly applies to losses (which is disadvantageous to

taxpayers); whether it also applies to gains is uncertain.

4.

Assignment of Income Doctrine: Income from services is taxed to the

one who performs the services. Lucas v. Earl, 281 U.S. 111 (1930).

© Steven J. Willis All Rights Reserved

1

Income from property is taxed to the owner of the property. Helvering v.

Horst, 311 U.S. 112 (1940).

5.

Burgess/Battlestein Scenario: A taxpayer may not “pay” an amount with

funds borrowed from the creditor immediately prior to the attempted

“payment.” Battlestein v. Commissioner, 631 F.2d 1182 (5th Cir. 1980)

(en banc). A taxpayer, however, may borrow funds from a third party

and then effectuate a “payment” using those funds. Economically, the

two transactions are identical. Legally, however, they are different.

Under the Burgess decision, a taxpayer may borrow from a creditor,

commingle the funds with other funds, wait some period of time (see the

Old and Cold Doctrine) and then successfully “pay” the creditor/lender.

6.

Business Purpose Doctrine: If a transaction has no Substantial Business

Purpose other than tax avoidance or reduction of income tax, the law will

not respect the transaction. This doctrine arose from Gregory v.

Helvering, 293 U.S. 465 (1935), which also addressed the Substance

Over Form Doctrine.

7.

Cash Equivalence Doctrine: An unsecured promise to pay of a solvent

obligor, readily transferable, not subject to set-off, and not subject to a

discount substantially greater than the prevailing market rate is the

equivalent of cash. Cowden v. Commissioner, 289 F.2d 20 (5th Cir.

1961). As such, the fair market value of the promise is includible in

income upon receipt by a cash method taxpayer. Under the Schlude

Doctrine, it is also likely includible in the income of an accrual method

taxpayer.

8.

Chevron Deference: The judiciary must defer to an executive agency's

interpretation of a statute that the agency administers, provided that the

agency's interpretation is reasonable. Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. National

Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984).

9.

Commerciality Doctrine: Organizations which are overly commercial are

not entitled to exempt status under § 501(c)(3) and its predecessors.

Better Business Bureau of Washington, D.C., Inc. v. United States, 326

U.S. 279 (1945).

10. Claim of Right Doctrine: When a taxpayer receives funds (which

represent earnings) with a contingent obligation to repay, either because

the sum is disputed or mistakenly paid, and no limitation on the use of

the funds exists, those funds are included in the taxpayer’s income in the

year they are received. North American Oil Consolidated v. Burnet, 286

U.S. 417 (1932). This rule applies to cash method taxpayers. Whether

it also applies to accrual method taxpayers is an issue of the Schlude

Doctrine.

© Steven J. Willis All Rights Reserved

2

11. Cohan Rule: If the amount of an expense cannot be proved specifically

by the taxpayer, the trier of fact may nevertheless estimate a reasonable

amount. If an amount has clearly been expended, to allow nothing

because of inadequate documentation is unreasonable. Cohan v.

Commissioner, 39 F.2d 540 (2d Cir. 1930). Caution: Congress has

superseded this doctrine in many areas. For example, § 274(d)

disallows travel and entertainment expenses (the type involved in

Cohan) without adequate records corroborating the taxpayer’s

testimony. Similarly, § 170(f)(11) requires documentation for most

charitable contributions.

12. Constructive Receipt Doctrine: A cash method taxpayer has income

when the proceeds are available to him, without substantial limitations,

and he refuses or neglects to accept them. Knowledge of the availability

is generally a necessary factor, as well. This doctrine arises from Treas.

Reg. § 1.451-2(a). The Cowden v. Commissioner, 289 F.2d 20 (5th Cir.

1961) gloss holds that a taxpayer may decline to enter into a contract

which would offer current receipt; hence, a taxpayer may delay receipt

without invoking the Constructive Receipt Doctrine if he does so at the

inception of the contract. Also, under Martin v. Commissioner, 96 T.C.

814 (1991), a cash method taxpayer may sometimes modify a contract,

after partial performance, to defer receipt of payments without triggering

the Constructive Receipt Doctrine.

13. Corn Products Doctrine: The § 1221 list of non-capital assets is

illustrative rather than exclusive. Corn Products Refining Co. v.

Commissioner, 350 U.S. 46 (1955). This doctrine was effectively

eliminated by the Arkansas Best exception pursuant to which the Corn

Products Doctrine applies only to hedging transactions. Arkansas Best

Corp. v. Commissioner, 485 U.S. 212 (1988).

14. Court Holding Company Doctrine:

Under the assignment of income

doctrine, transferee completion of a transaction negotiated and fully

arranged by a transferor may be attributed to the transferor along with an

imputed transfer of the proceeds. Commissioner v. Court Holding Co.,

324 U.S. 331 (1945). This doctrine is related to the Substance over

Form Doctrine.

15. Crane Rule: The “amount realized” from a taxable event includes the

amount of the transferor’s debt assumed by the purchaser. It also

includes the amount of debt to which the property is subject, even if the

debt is not “assumed.” This rule applies both to recourse and nonrecourse liabilities. It applies to secured and unsecured debt. It also

applies even if the amount of the debt exceeds the fair market value of

the property. Crane v. Commissioner, 331 U.S. 1 (1947), as modified by

© Steven J. Willis All Rights Reserved

3

Commissioner v. Tufts, 461 U.S. 300 (1983). Many people mistakenly

cite the Crane Rule as: The basis of property acquired with borrowed

money includes an amount equal to the borrowed money used. This

corollary resulted from: Parker v. Delaney, 186 F.2d 455 (1st Cir. 1950).

16. Crummey Trust Doctrine: A grantor is allowed a § 2503(b) annual

exclusion amount for a gift of a future interest in trust to the beneficiary if

the beneficiary is granted a Crummey power. The Crummey power

entitles the beneficiary the right to demand ownership of the deposited

property for a limited period of time, which this 9 th Circuit court found to

be equivalent to a present or completed interest for gift tax purposes.

Crummey v. Commissioner, 397 F.2d 82 (9th Cir. 1968).

17. Davis/Kenan Gain: The use of appreciated property to satisfy an

obligation or to acquire something of value is a taxable event. United

States v. Davis, 370 U.S. 65 (1962). Kenan v. Commissioner, 114 F.2d

217 (2d Cir. 1940).

18. Destination of Income Test: The purpose for which funds are expended

is irrelevant to whether the earning of the funds were related to an

exempt purpose. This test resulted from Congressional unhappiness

with the case of C. F. Mueller Co. v. Commissioner, 190 F.2d 120 (3rd

Cir.1951). The test appears in §§ 502 and 513.

19. Duty of Consistency: Arising from R.H. Stearns Co., 291 U.S. 54 (1934),

the duty is related to and overlaps with estoppel, as well as the Doctrine

of Equitable Recoupment (although it applies quite differently). The

Court explained: “no one shall be permitted to found any claim upon his

own inequity or take advantage of his own wrong.” A 1997 Tax Court

case listed the Duty’s factors as: ‘‘(a) The taxpayer made a

representation of fact or reported an item for tax purposes in one tax

year; (b) the Commissioner acquiesced in or relied on that fact for that

year; and (c) the taxpayer desires to change the representation

previously made in a later tax year after the earlier year has been closed

by the statute of limitations.’’ Estate of Letts v. Commissioner, 109 T.C.

290, 296 (1997). This Duty of Consistency is not consistently applied

and is arguably often ignored. It exists as a potent, but ill-defined and

underused government weapon.

20. Economic Benefit Doctrine: A cash method taxpayer has income when

he receives the economic benefit of the proceeds. This can occur even

if he lacks actual receipt, constructive receipt, or receipt of a cash

equivalent. It results when the payor irrevocably places funds for the

benefit of the taxpayer beyond the reach of the payor’s creditors. Sproull

v. Commissioner, 194 F.2d 541 (6th Cir. 1952). According to most

authorities, the Doctrine applies only to service income and contest

© Steven J. Willis All Rights Reserved

4

winnings; it does not apply to transactions involving the sale of property.

The government has consistently, but unsuccessfully, disagreed with this

limitation on the Doctrine.

21. Equitable Recoupment Doctrine: Parties timely litigating a tax claim –

income or deduction – may recoup a tax-barred related claim from the

same transaction which resulted in inconsistent treatment. Bull v. United

States 295 U.S. 247 (1935). Stone v. White, 301 U.S. 532 (1937).

United States v. Dalm, 494 U.S. 596 (1990). Whether the Doctrine

applies in the Tax Court is controversial.

Estate of Mueller v.

Commissioner, 107 T.C. 189 (1996) (en banc) (reversed by the Sixth

Circuit).

This equitable doctrine is superseded by the seven

circumstances of adjustment found in section 1312 (even if the

application of mitigation fails for some reason other than the lack of a

listed circumstance). As a result, the doctrine typically applies when two

different types of taxes are involved, such as an income tax and an

estate tax, gift tax, excise tax, or alternative tax.

22. Erroneous Deduction Exception: Recovery of an item erroneously

deducted does not result in Tax Benefit Rule income: the Tax Benefit

Rule applies only to items properly deducted in another period. This

controversial exception to the Rule applies in the Tax Court for cases

appealable to circuits other than the Fifth or Ninth. Hughes & Luce

L.L.P. v. Commissioner, 70 F.3d 16 (5th Cir. 1995). Unvert v.

Commissioner, 656 F.2d 483 (9th Cir. 1981). The Exception is

consistent with § 1312(7). Arguably, the Fifth and Ninth circuits judicially

repeal much of § 1312(7) by their rejection of the Exception.

23. Form Over Substance Rule: This is the corollary to the Substance Over

Form Doctrine. Sometimes, courts respect form, finding that taxpayers

are entitled to organize their transactions to reduce taxes. Gregory v.

Helvering, 293 U.S. 465 (1935). Also important, is the use of this Rule

to prevent a taxpayer from disavowing his own chosen but detrimental

formalities: “You made your bed, so lie in it.” Note that the Gregory

decision stands both for the Form Over Substance Rule and the

Substance Over Form Doctrine.

24. Family Hostility Rule:

Family hostility may militate against the

application of statutory rules governing attribution of stock ownership.

This rule has applied in relation to § 318; however, it has not traditionally

applied in relation to §§ 267 and 4946.

25. Golson Rule: The Tax Court is bound to follow cases decided by the

Circuit Court to which the case before it is appealable. Golson v.

Commissioner 54 T.C. 742 (1970). This controversial Rule sometimes

results in a Tax Court Judge signing an opinion with which he disagrees

© Steven J. Willis All Rights Reserved

5

and then issuing an opposite ruling, appealable to a different Circuit,

during the same term. Because the Tax Court is a national court,

opinions from which are appealable to twelve Circuits, this anomaly

results.

26. Idaho Power Rule: Depreciation expense and other material costs must

be capitalized to the extent the underlying assets contributed to the cost

of a long-term asset. Commissioner v. Idaho Power Co., 418 U.S. 1

(1974).

27. Integral Part Doctrine: This un-codified doctrine applies mostly in the tax

exempt arena. It holds that an entity may achieve exempt status if its

activities are an integral part of another exempt organization and they

further the exempt purpose of the other organization. The Doctrine

applies even though the separate entity’s activities do not by themselves

justify exempt status. See, Treas. Reg. § 1.502-1(b).

28. Legislative Grace Doctrine: An income tax deduction is a matter of

legislative grace. The burden of clearly showing the right to the claimed

deduction is on the taxpayer. Interstate Transit Lines v. Commissioner,

319 U.S. 590 (1943). In contrast, § 61 broadly taxes all income.

29. Matching Principle: For Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, the

Matching Principle requires that income be matched in the same period

with the costs required to produce it. Very generally, this rule applies for

tax purposes as part of the Accrual Method of Accounting; however,

violation of the rule is common. See, the Schlude Rule. No general

Matching Principle of income and deduction timing or character between

taxpayers exists. But see, Albertson’s Inc. v. Commissioner, 42 F.3d

537 (9th Cir. 1994). In some instances, such as §§ 267 and 404, the

code requires matching of income and deductions for timing. This,

however, is a legislative rule, not a general principle of tax law. Indeed,

its existence in some statutes supports the proposition that it does not

exist generally: otherwise, it would be unnecessary to state in a statute.

30. Old and Cold Doctrine: This unstated rule is generally known to tax

practitioners. At some points, events are so old and cold that they

acquire reality by themselves and cease to be part of an overall plan or

transaction; hence, the Substance Over Form Doctrine would not apply.

How long this takes is unclear.

31. Old Colony Rule: The form of the income does not matter in terms of

“whether” an item is income; hence, a taxpayer may have income upon

the receipt of cash, property, services, or even when an obligation is

satisfied on his behalf. Old Colony Trust Co. v. Commissioner, 279 U.S.

716 (1929).

© Steven J. Willis All Rights Reserved

6

32. Open Transaction Doctrine: A taxpayer need not recognize gain in an

“open transaction” until he has recovered his capital. Burnet v. Logan,

283 U.S. 404 (1931). Open transactions are rare, particularly since

statutory changes to § 453 in 1980. Typically, they involve the receipt of

rights so speculative that they lack a determinable value. An example

might involve the transfer of property in exchange for a percentage of

revenue from a future transaction under circumstances in which the

future transaction cannot realistically be valued.

33. Rabbi Trust Doctrine: A transfer of funds for the benefit of a taxpayer

which remain subject to the claims of the transferor’s creditors does not

trigger the Economic Benefit Doctrine. The doctrine arose from a fact

pattern involving a synagogue and a rabbi. Ltr. Rul. 8113107.

34. Realization Event Doctrine: Mere appreciation in value of an asset will

not generally result in income; instead, some “realization event” such as

a sale or exchange is typically necessary. See, Commissioner, v.

Glenshaw Glass, 348 U.S. 426 (1955). See also, Cottage Savings

Association v. Commissioner, 499 U.S. 554 (1991). After Glenshaw

Glass, most authorities presumed this requirement was of constitutional

significance; however, after Cottage Savings, the more common view is

that is it more for administrative convenience.

35. Res Judicata: Every year constitutes a separate cause of action for tax

law. Hence, a final decision that an item of income must be reported in a

particular year is not res judicata regarding whether the same item must

be reported in a different year: each year is a separate cause of action.

The decision may, however, collaterally estop a party from acting

inconsistently. The difference is important: while res judicata is an

absolute bar, collateral estoppel is equitable and can be overcome by a

change in law or jurisprudence. Commissioner v. Sunnen, 333 U.S. 591

(1948).

36. Schlude Doctrine: Accrual method taxpayers that receive prepaid

amounts for services must include them in income upon receipt. Schlude

v. Commissioner, 372 U.S. 128 (1963). This Doctrine is controversial,

but well-settled. A few – but very few – judicial exceptions exist.

Several statutory exceptions exist, such as §§ 455 (subscriptions), 456

(dues), 467 (rent), and 1272 (interest).

37. Skelly Oil Doctrine: A deduction for repayment of an amount not fully

taxed in a prior year may be limited to the portion taxed. United States v.

Skelly Oil Co., 394 U.S. 678 (1969).

© Steven J. Willis All Rights Reserved

7

38. Sham Transaction Doctrine: “Sham” transactions are ignored for tax

purposes. Knetsch v. U.S., 364 U.S. 361 (1960). This is an extension of

the Substance Over Form Doctrine. It tends to apply to egregious

cases, including ones involving fraud.

39. Substance Over Form Doctrine: The substance of a transaction controls

over its form. Effectively, only the government may make this argument.

Taxpayers – because they choose the form of their transactions – rarely,

if ever, successfully disavow their chosen form in favor of the economic

substance. Gregory v. Helvering, 293 U.S. 465 (1935).

40. Tax Benefit Rule: An event “fundamentally inconsistent” with a proper

beneficial deduction in an earlier year sometimes results in income.

Hillsboro National Bank v. Commissioner, 460 U.S. 370 (1983). A

corollary exclusionary aspect of the rule appears in many early cases

and is codified in § 111.

© Steven J. Willis All Rights Reserved

8