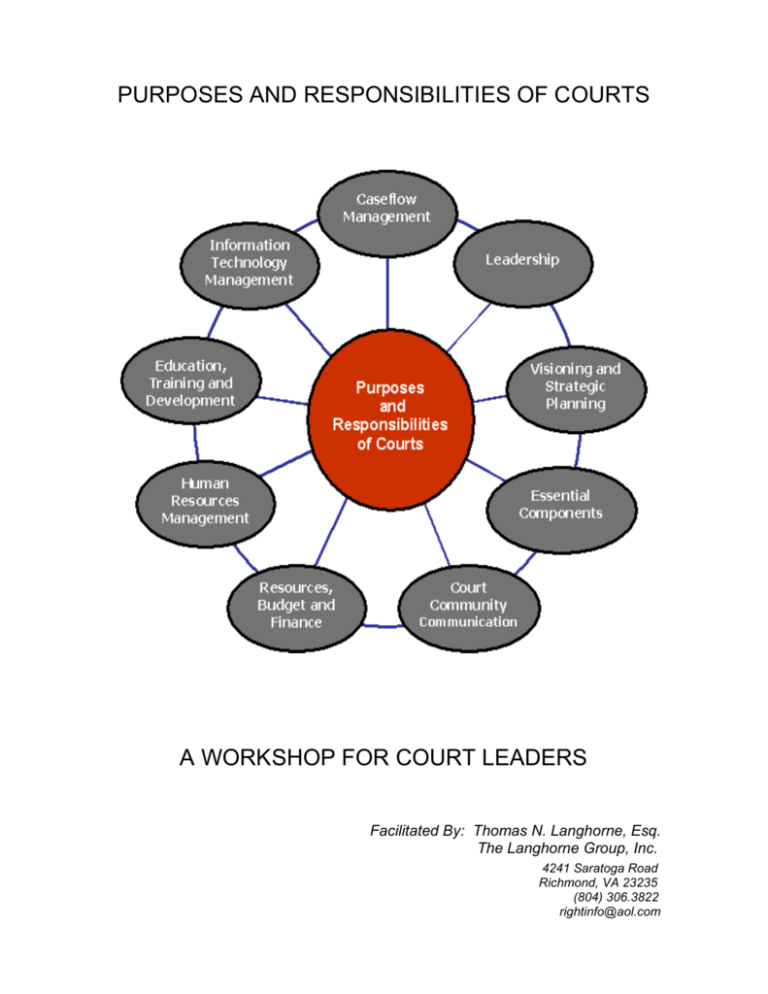

Purposes and Responsibilities of Courts

advertisement