Enforcing possession order

Seeking & enforcing possession orders

Part 1: the rent arrears protocol

1.

During the Access to Justice inquiry Lord Woolf became convinced that codes of practice for pre-action conduct were needed for common types of dispute that were often of low value but which were frequently litigated. New litigation post CPR has reduced by 80% in the High Court and 25% in the County court and protocols have been a factor in this (White Book [2006] C1A-005). Housing practitioners have generally welcomed the effect of the Protocol for Housing Disrepair Cases.

2.

However, it seems likely that the Rent Arrears Protocol (which applies only to social landlords) will be less enthusiastically received by social landlords because: a) Social landlords have not hitherto rushed off to court without taking appropriate steps to resolve the tenant’s rent arrears (see for example

Housing Dispute

Resolution – SHLA’s response to the Law Commission, July 2006 available at www.shla.org.uk

) . Hence the need for the protocol is debatable. b) Social landlords do not usually issue possession claims without good reasons namely that the tenant has failed to demonstrate an ability to pay off arrears within a reasonable period. In these circumstances the protocol is unlikely to see a significant reduction in possession claims. c) The protocol places onerous obligations on the landlord to do things that are properly the responsibility of the tenant. The protocol may therefore encourage the tenant to be passive in the face of escalating rent arrears. d) By applying only to social landlords the protocol means that social landlords should be treated differently from private landlords in circumstances where their statutory rights, such as under the Housing Act 1988, are the same. e) The protocol creates a tension with the landlord’s legal rights, which could give rise to satellite litigation.

3.

When breaches of the protocol are alleged it should be noted: a) Protocols are not statutes; they derive their authority from a Practice Direction. b) The court should not be concerned with minor infringements but will be concerned to see that the substance of the protocol has been followed (PD –

Protocols, 2.2). c) Infringements should primarily be relevant where non-compliance has led to the commencement of proceedings which might otherwise not have needed to be commenced (PD – Protocols, 2.3).

4.

When the protocol is followed it should be much easier for the landlord to establish: a) That it is reasonable to make a possession order. b) That a possession order should not be postponed.

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

5.

Indeed outright possession orders should become the usual type of order given that before the landlord can get its claim determined in court the tenant may have breached five agreements to reduce his/her arrears as agreements should be made before: a) a NSP is served (para 2), b) proceedings are issued (para 10), c) a breach of the above agreement is acted on (para 10), d) the 1 st

hearing, in which case the claim should be adjourned (para 13(b)), e) a breach of the above agreement is acted on ie before restoring an adjourned hearing (para 13(c)).

6.

Furthermore, a high onus is put on social landlord to: a) ascertain the cause of the arrears (paras 1), b) address any difficulty that a tenant may have in understanding or dealing with his/her situation (para 4), c) assist in securing arrears from the DWP (para 5) or with securing HB (paras 6 &

7).

Part 2: fallout from Harlow DC v Hall [2006] HLR 498

7.

Since 3rd July 2006 PD 55 (Possession Claims) has been amended to provide for nodate possession orders as outlined by the Court of Appeal in Hassan v Bristol CC

[2006] HLR 551. The amendments, which apply only in respect of secure tenancies, give weight to the argument that landlords should avoid this sort of possession order if possible because they will create a new and unnecessary stage in the eviction process.

Essentially, no-date possession orders insert a 2nd stage between the obtaining of a possession order (‘the 1st stage’) and the enforcement of a possession order (‘the 3rd stage’).

8.

The amendments to PD55 provide as follows: a) A new Form N28A, Order for possession (rented premises)(postponed) , is created. b) The 2nd stage is begun by the landlord giving the tenant a 14-day notice of intention to apply for a possession date (PD 55 10.3). This notice must contain specified information (10.4) and gives the landlord a 3-month window within which to apply for a possession date. c) The landlord seeks a possession date by filing an application notice in accordance with CPR 23, including the issue fee (10.6), but without serving it on the tenant

(10.8). d) The application is normally determined without a hearing by the district judge fixing possession for the next working day (10.9). However, the district judge has power to fix a date for the application to be heard and to direct service of the application notice and supporting evidence on the tenant (10.9).

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

9.

The following issues arise: a) Does the concept of tolerated trespasser apply to assured tenants? The Court of

Appeal will shortly consider this issue in April in White v Knowsley Housing

Trust .

10.

b) When should the court’s power to make a no-date possession orders be exercised?

Part 3: obtaining possession orders

The test of ‘reasonable to make a possession order’

11.

The test has existed since shortly after the First World War and the classic definition was given in by Lord Greene MR in 1942:

‘the duty of the judge is to take into account all relevant circumstances as they exist at the date of the hearing. That he must do in what I venture to call a broad commonsense way as a man of the world, and come to his conclusion giving such weight as he thinks right to the various factors in the situation.’

Cumming v

Danson [1942] 2 All ER 653, @655

Postponed or outright?

12.

Over the last decade or two it has become easier to get a possession order but harder to enforce it. In order to overcome this problem landlords are now less inclined to seek postponed possession orders. In rent arrears cases postponed orders are frequently made without the court properly considering whether the tenant is able to pay off the arrears within a reasonable period. As Templeman LJ said:

‘In my judgment an order for possession should, in general, either be enforced, or be discharged, or it can be suspended, but it should only be suspended for a defined period. If the order is suspended for a defined period, that period should not extend into the mists of time, but should have some relevance to the facts existing at the date when the order for suspension is made.’

Vandermolen v Toma

(1981) 9 HLR 91

13.

After citing the above passage the Court of Appeal in another case noted that the essential purpose of a stay or suspension of a possession order in a rent arrears case is:

‘that the landlord should eventually be paid the arrears of rent due to him and that he should obtain such payment within a reasonable time’

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

and that accordingly a postponed possession order should not be made in cases where an almost indefinite period will be required before the arrears will be paid off ( Taj v Ali

(No. 1) (2001) 33 HLR 253, paras 6 & 16).

14.

What is a reasonable period of time? a) In Taj v Ali (No. 2) in circumstances in which the tenant applied to suspend a warrant to the Court of Appeal after it had made an outright possession order it was held that the court would not wish to encourage repeated applications to stave off the execution of an outright order. It stated that a period of 5 years suspension would be very near the limit in the circumstances of that particular case for allowing a tenant to pay off his arrears (para 16). b) As a rule of thumb a tenant should not be given more than 6 years to pay off his arrears having regard to the fact that permission is required to enforce a warrant six or more years after the date of a possession order (CCR Ord 26r5(1)(a)).

Furthermore, if a landlord applies for permission more than 6 years after its entitlement to possession permission may well be refused ( Patel v Singh [2002]

EWCA Civ 1938). c) The fact that borrowers are frequently given extended periods within which to pay off mortgage arrears (see Cheltenham & Gloucester BS v Norgan [1996] 1 WLR

343) is not relevant to tenant possession claims where the landlord’s debt is not secured and interest on the arrears and the cost of court hearings cannot be added to any security. This distinction was observed in Taj v Ali (No. 1) (2000) 33 HLR

253, para 7. d) Contrary to what tenants frequently assert Lambeth LBC v Henry (1999) 32 HLR

874 is not an authority for the proposition that extended periods, such as 23 years in that case, can be given to tenants for paying off arrears. The view is erroneous because: i) the court in Henry thought that the Norgan principles of mortgage possession cases were relevant, contrary to what was subsequently decided in Taj v Ali (no. 1) , and ii) Henry was a case in which the tenant sought to set aside a possession order on grounds of his non-attendance at the trial several years earlier; hence the court’s view on ‘a reasonable period’ was obiter.

These points were accepted by HHJ Oppenheimer in a recent county court appeal

( Catalyst Communities HA Ltd v Cole , Brentford CC, 7/11/06).

15.

Because courts frequently overlook the reasonable repayment period they frequently concentrate on the level of arrears to the exclusion of the rate at which a tenant can repay them. For example, if there are rent arrears of £1,000 and the tenant is only offering to pay them off at a weekly rate of £2.50 then it will take him/her over 7 years to clear the arrears. But a better off tenant with the same arrears who could repay them at £10 per week would have a much stronger case for obtaining a postponed order.

There is no rule of law that limits a defaulting tenant, even one on welfare benefits, to reducing his/her arrears at only £2.85 per week, although the court should satisfy itself that the tenant has the ability to pay the offered sums.

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

Postponed subject to conditions

16.

It is usually overlooked that a possession order can be postponed subject to such conditions as the court thinks fit (HA 1985 s85(3), HA 1988 s9(3). Accordingly, an order could be worded as follows:

1. The court has decided that unless the defendant makes the payments as set out in paragraph 3 s/he must give the claimant possession of the property known as xxx on xxx.

2.

The defendant must also pay to the claimant £(a) for unpaid rent, use and occupation of the property and £(b) for the claimant’s costs.

3.

The defendant must pay the claimant the total amount of £(a)+(b) by instalments of £xxx per week in addition to the current rent. The current rent is £xxx per week.

The first payment of both these amounts must be made on or before xxx.

4. The defendant must also comply with the terms of his/her tenancy agreement until the claimant regains possession of the property. This is so even if the claimant’s tenancy comes to an end under paragraph 1 and hence even if the tenancy terms cease to bind the claimant.

5. If the defendant pays the total amount mentioned in paragraph 3 in the manner set out in paragraph 3 the claimant will not be able to take any steps to evict the defendant as a result of this order.

6. If the defendant does not pay the total amount mentioned in paragraph 3 in the manner set out in paragraph 3 then the claimant can ask the court bailiff to evict the defendant and remove his/her goods to obtain payment.

17.

With the above wording if the tenant breached the repayment terms then s/he would become a tolerated trespasser but remain subject to the terms of his/her tenancy agreement. This would obviate at a stroke the problems associated with tolerated trespass from the landlord’s perspective. The fact that the occupier would become a tolerated trespasser would offend no principle of justice but should be seen as a proportionate outcome of his/her failure to pay off his/her rent arrears as ordered.

What evidence to adduce?

18.

If the landlord wants an outright possession order it should adduce evidence that supports its case, and, a point that is often overlooked, plead reliance on it:

‘In considering whether it is reasonable to make an order … the judge should consider all the relevant circumstances: but that is not a consideration at large. It is, or should be a consideration in accordance with the pleadings. In my judgment, the matters proposed to be relied upon by the landlord in support of the contention that it would be reasonable to make an order for possession … must be pleaded by the landlord.’ Laimond Properties Ltd v Raeuchle (2001) 33 HLR 113, CA.

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

19.

Paragraph 8 of the prescribed particulars of claim form, N119, invites landlords to plead such matters. With social landlords rent arrears should be viewed as money that would otherwise have been used for the benefit of others. This is a point that should be spelt out in the particulars of claim. For example:

‘The claimant cannot afford to carry a debt of this size. It relies on rental income to provide a service to all its tenants. Rental income is re-invested in the claimant’s existing units and allows it to carry out cyclical repairs and decorations. For example, £3,000 could typically be used to provide a new kitchen or two new bathrooms.

‘The claimant’s lenders look at its ability to collect rent when assessing its viability for loans, which would then enable it to provide new homes for homeless people. Tenants’ debts affect the claimant’s financial viability.

‘The claimant’s officers have spent a considerable amount of time supporting the defendant and dealing with the problems caused by her debt. This is time that could have been spent assisting other tenants.’

Part 4: warrant suspensions

20.

A possession order, whether postponed or outright, means what it says: the landlord’s right to possession has been established, save that with a postponed order this right is postponed ( Thompson v Elmbridge BC [1987] 1 WLR 1425). But whether postponed or not it is the possession order that determines the parties’ rights. The centrality of the possession procedure is evident from the statutory scheme that:

requires a landlord to obtain a possession order (HA 1985 s82(1), HA 1988 s5(1)),

requires a notice seeking possession with grounds and particulars,

puts the burden of proof in possession proceedings on the landlord, and

in a discretionary case, requires the landlord to show that it is reasonable to make a possession order (HA 1985 s84(2) and HA 1988 s7(3)).

establishes a specific and detailed court procedure, with a pre-action protocol, that is designed to meet the overriding objectives of the civil procedure rules (CPR 55).

21.

What follows after a possession order has been obtained is merely an administrative way of giving rise to the earlier judicial determination. Enforcement of a possession order does not involve any issues of civil rights or obligations and unless the tenant applies to halt the process enforcement requires no judicial involvement ( Southwark LBC v St

Brice [2002] 1 WLR 1537, para 32).

22.

The court’s power to suspend enforcement of a warrant should not be used to disregard the fact it is the possession order that established the landlord’s right to possession. This is so even if, with the passage of time, the landlord’s original right to possession has disappeared so that if the matter were reconsidered the landlord would no longer have a right to possession. The basis for this rule is that there must be finality in a possession claim and that applications to suspend warrants cannot be used to establish a re-hearing of the claim. In circumstances where an outright order were made this would mean that

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

the power to suspend should be exercised in very limited circumstances ( Goldthorpe v

Bain [1952] 2 QB 455, CA).

23.

In order to suspend a warrant the tenant needs to be able to show an ‘unexpected and significant change of circumstances’ since the possession order was made, of which the court has proper evidence ( Taj v Ali (No. 2) (2000) 33 HLR 259, para 12). The burden of proof on an application to suspend is on the occupier ( Southwark LBC v St Brice , para 40).

24.

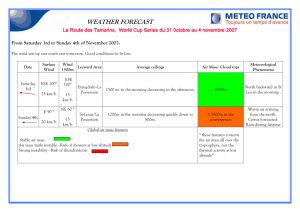

A possession order is denied its significance unless it is appreciated that (a) it determines the rights of the parties, and (b) warrant suspensions require compelling circumstances established with proper evidence. What has tended to happen over the last decade or two is that the obtaining of a possession order has, if postponed, becomes merely a hurdle that a landlord has to climb before embarking on the far more onerous tasks of being able to enforce a warrant. This has created the sort of problems that are illustrated by the attached graph, which shows how in one case judges granted seven warrant suspensions over six years whilst the occupier’s arrears increased from £3,000 to £12,000. On appeal HHJ Oppenheimer overturned the seventh warrant suspension as being irrational: the only reason given by the district judge being that the occupier should be given one more chance.

Warrant suspensions - procedure

25.

It is not unknown for courts to list applications to suspend warrants in anti-social behaviour cases as if they were trials with both parties being required to put in witness statements as a prelude to the court hearing live evidence on the hearing of the application. The Court of Appeal has established that on an application to suspend a warrant the landlord cannot be required to prove again what he has already proved when establishing its right to possession ( Southwark LBC v St Brice paras 17 & 40).

Accordingly, when an occupier applies to suspend a warrant the focus of attention will be on whether s/he has established a compelling reason to halt the administrative process of enforcement.

26.

Ordinarily, even in anti-social behaviour cases, warrant suspension cases should be done on a summary basis with the court reading witness statements. This approach is envisaged by the Civil Procedure Rules: ‘the general rule is that evidence at hearings other than the trial is to be by witness statement’ (CPR 32.6). The situation may be different when the landlord seeks to rely on facts that were not connected to the ground for possession, such as when it seeks to rely on evidence of anti-social behaviour having obtained a possession order on rent arrears grounds. But even in these situations the

Court of Appeal has noted the overriding principles contained in the Rules ‘and in particular the need for applications to be dealt with in a summary and proportionate manner’ ( Sheffield CC v Hopkins [2002] HLR 12, para 29(b)).

Make a note of judgment

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

27.

In Ealing LBC v Richardson [2006] HLR 13 Mrs Richardson successfully made nine applications to suspend a warrant whilst her arrears increased over nine years from

£2,000 to £5,000. The Council sought a re-hearing on the grounds that details of Mrs

Richardson’s eight previous applications to suspend the warrant had not been before the

District Judge. This argument got short shrift when it was pointed out that the Council had been responsible for preparing a bundle for the hearing before the District Judge.

But in any case it begs the question as to what information the Council had kept of the eight previous hearings over nine years.

28.

When the District Judge suspended the warrant for the ninth time she referred to Mrs

Richardson as being ‘at the doors of “Last Chance Saloon”’ yet advocates know that when warrants are suspended judges invariably state that this is the occupier’s ‘last chance’. The difficulty is that these comments tend not to be recorded and hence they tend not to be shown to the judge on the next occasion. District Judges need to know how many ‘last chances’ the occupier has already been given and they need to know why warrants were suspended on previous occasions. This information will not be found on the court order or court file and the landlord’s advocate should prepare a note of judgment. If the occupier was represented the note should be agreed with this representative. It may even be prudent to get the judge’s approval. (The cost of doing this is included in the advocates’ brief fee, CPR PD 52 para 5.14.)

Part 5: how to avoid discretionary grounds for possession

Mandatory ground 8

29.

The tenant’s right to apply to suspend a warrant effectively only applies when possession has been made on a discretionary ground (Housing Act 1980, s89).

Parliament has given landlords of assured tenants, such as registered social landlords

(‘RSLs’), a mandatory rent arrears ground: Ground 8 may be used when there are at least eight week’s unpaid rent. If possession is obtained on this mandatory ground then the court’s order should not normally be suspended for more than 14 days. The only flexibility on the court’s power is that enforcement may be suspended for a maximum of six weeks where this is necessary to avoid exceptional hardship. The six week period starts on the day the possession order was made (Housing Act 1980, s89).

30.

The use of mandatory Ground 8 in rent arrears cases need cause no unfairness to the tenant because where there are exceptional circumstances for the existence of the rent arrears then the court has the power to adjourn the possession claim ( North British HA v

Matthews (2005) 1 WLR 3133 - but note the narrow definition given to ‘exceptional circumstances’: the fact that arrears are attributable to maladministration on the part of the housing benefit authority is not an exceptional circumstance (para 32)). Moreover, having obtained the possession order the landlord could opt not to enforce it, for example, if the tenant’s circumstances materially change.

31.

Before embarking on a ground 8 claim RSLs should note that Housing Corporation

Regulatory Circular 07/04 (para 3.1.4) requires the landlord to have first pursued other alternatives to debt recovery. It also notes that where ground 8 forms part of an arrears

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

and eviction policy, tenants should have been consulted and the governing board should have approved the policy.

32.

Some RSL tenancy agreements prohibit the use of ground 8. In these circumstances the tenant may be able to obtain an injunction to prevent breach of contract if ground 8 was used. Any such prohibition should be removed if an RSL wishes to rely on ground 8.

33.

Landlords who obtain a ground 8 possession order must also ensure that this fact is stated on the face of the order ( Capital Prime Plus plc v Willis (1998) 31 HLR 926,

CA).

Demotion as an alternative to a postponed possession order

34.

There is no mandatory ground for possession in respect of anti-social behaviour. Where the anti-social behaviour is serious an outright order will often be made (see Bristol CC v Mousah (1998) 30 HLR 32, CA). Problems with enforcement usually arise when the evidence was not strong enough to justify an outright order with the result that a postponed order was made. Given a choice between a postponed order and a demotion order social landlords would be well advised to seek the latter.

35.

Demotion orders should be easier to obtain than postponed possession orders because if this were not so then few landlords would seek them and this cannot have been

Parliament’s intention. Indeed Parliament’s intention seems clear from the legislation: the basic requirements for obtaining a demotion order are easier to satisfy, for example the conduct only needs to be ‘ capable of causing’ rather than ‘ likely to cause’ a nuisance or annoyance (Housing Act 1996 s153A).

36.

RSLs are concerned at the possibility that their decisions to terminate a demoted tenancy could be susceptible to judicial review. Hitherto, RSLs have not been found to be judicially reviewable ( Peabody Housing Association Ltd v Green (1978) 38 P&CR

644). But in recent years the High Court has adopted a less restrictive approach towards identifying whether a body is susceptible to judicial review ( R v Panel on Takeovers and Mergers ex p Datafin [1987] QB 815) and it may be that an RSLs decision to terminate a demoted tenancy could be judicially reviewed. It is assumed in Defending

Possession Proceedings , 6 th

ed, para 8.97 that this is so.

37.

There are, however, strong arguments for finding that RSLs seeking to enforce a demotion order are not judicially reviewable: a) The landlord is relying upon a private law power that arises from a contract and statutory right (see R v (1) Servite Houses (2) Wandsworth LBC ex parte

Goldsmith (2001) LGR 55). b) The decision is a private one affecting one tenant and one landlord which raises no issue of public concern or interest. c) Parliament required local authorities to have review procedures when evicting demoted tenants (Housing Act 1996, s143F) because without them too many cases would end up as judicial reviews. Parliament did not make this a requirement for

RSLs because it did not envisage them being susceptible to judicial review.

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

Part 6: Costs

38.

Even if the warrant is suspended the landlord should normally be awarded its costs on the basis that the occupier’s own conduct made the application to suspend necessary and that it only succeeded because the court granted him/her an indulgence (CPR 44.3).

39.

Although enforcement of a costs order may seem unlikely it should be sought because it: a) may be, or become at a later date, enforceable, b) may be set off against any subsequent successful claim that the occupier brings against the landlord R (Burkett) v Hammersmith and Fulham LBC [2004] EWCA

Civ 1342), c) signifies that the occupier has obtained the court’s indulgence, and d) may help the landlord to put figures before the court on future occasions as to the cost of having to enforce postponed possession orders.

Jon Holbrook

8 th

January 2007

Jon Holbrook copyright January 2007

Catalyst Communities HA Ltd v Colemack

Rent arrears Jan 2000 – Oct 2006 (Monthly snapshot)

14000

12000

10000

8000

6000

4000

2000

0

01

/0

1/2

00

0

A pr

-00

Jul

-00

O ct-

00

Jan

-01

A pr

-01

Jul

-01

O ct-

01

Jan

-02

A pr

-02

Jul

-02

O ct-

02

Jan

-03

A pr

-03

Jul

-03

O ct-

03

Jan

-04

A pr

-04

Jul

-04

O ct-

04

Jan

-05

A pr

-05

Jul

-05

O ct-

05

Jan

-06

A pr

-06

Jul

-06

O ct-

06

Vertical lines show:

2000 June

2001 November

2002 June

2002 September

2003 August

Postponed possession order (c/r + £5 p/w)

1

2 st nd warrant suspension (c/r + £10 p/w) warrant suspension (c/r + £3 p/w)

3 rd warrant suspension (c/r + £3 p/w)

4 th warrant suspension (c/r + £3 p/w)

5 th warrant suspension (c/r + £3 p/w)

6 th

7 th warrant suspension (c/r + £5 p/w) warrant suspension (c/r + £5 p/w) set aside on appeal in November

2004 February

2004 October

2006 June

Jon Holbrook, London &

Owen White Solicitors, Slough