Sociology 530

advertisement

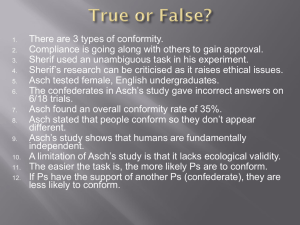

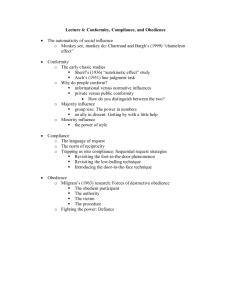

Sociology 319 Sociological Approaches to Social Psychology April 7, 2009: Group Cohesion & Conformity Emotions (cont’d) A. What accounts for individual-level variation in emotional reactions? 1. Social structural/socialization shapes the display of emotion, where people are socialized to believe that particular emotions are either appropriate or inappropriate for their social group. a. Gender. Women are believed to display (though not necessarily feel) more sadness, happiness, and anxiety than men. In earlier decades, women were believed to experience less anger than men, although more recent evidence suggest that women faced more rigid social constraints to not show anger. b. Ethnicity/culture. The classic People in Pain (1969; Zborowski) study compared the emotional expression and reaction to pain reported by Irish, Italian, Jewish and “Old American” (WASP) subjects. The studies found Italian and Jewish subjects to be highly expressive (e.g., crying complaining), while Irish were less so and WASP even more stoic in the face of pain. Presuming that the actual physical experience was similar across groups, the differences were attributed to cultural expectations and socialization. 2. Age a. Emotional reactivity declines with age. Older persons report less extreme sadness in the face of adversity, but less extreme joy in the face of positive events, relative to younger persons. b. Age-related decline reflects life experience, the development of coping skills, and the ability to take things “in one’s stride.” Some argue that there is a biological basis for such declines in emotional reactivity. c. Researchers continue to debate those characteristics of younger persons who have high versus low emotional reactivity. Data are not conclusive in support of either hypothesis. Competing hypotheses are: i. Steeling effects. Individuals who experience adversity early in life “toughen” up and can role with difficulties that come their way. They develop pro-active coping skills, and can manage both stress and the emotional consequences thereof. ii. Cumulative disadvantage hypothesis. Individuals who experience multiple adversities over time become worn down emotionally. Their coping abilities and perceived sense of control become compromised, and thus they have a more difficult time emotionally with life stressors. I. What is a Group? A. A group is a social unit that has two or more persons, and has ALL of the following characteristics. 1. Common goals: group members share at least one common goal to be achieved through joint action. 2. Interaction: The group members communicate with and influence one another. 3. Normative expectations: group members share a set of normative expectations (norms and roles) 4. Identification: group members consciously identify with the group and think of themselves as members. II. Majority Influence and Conformity A. Conformity 1. This refers to adherence by an individual to group norms or standards. It involves a change in behavior or beliefs as a result of real or imagined group pressure. A norm is a rule or standard that specifies how group members are expected to behave under given circumstances. Groups develop norms regulating a wide array of behaviors by members. 2. Conformity in groups should not be taken for granted; group members usually conform, but not always. The amount of influence exerted by the majority on the individual varies widely. There are two main forms of influence that provide conforming behavior in groups: normative influence and informational influence. a. Normative influence. This type of influence occurs when group members conform to expectations held by others (i.e., norms) in order to receive the rewards and or avoid punishments that are contingent on adherence to these expectations. This essentially involves “going along with the crowd” to avoid rejection or stay in people’s good favor.” b. Informational influence. This type of influence occurs when a group member accepts information from others as valid evidence about objective reality. Influence of this type is likely to occur in situations that involve uncertainty or that lack objective standards of reference. It also occurs on tasks where members attempt to discover a correct answer to a problem. Under these conditions, members will often rely on the group’s majority to gain a sense of what is valid or true. The majority exerts influence on individual members by providing information that defines reality and that serves as a basis for making judgments or decisions. i. Sherif (1936) autokinetic effect study. This is one of the most famous experiments in social psychology. Here, the study focused on a physical phenomenon called the “autokinetic effect.” This means that something can move by itself. The autokinetic. effect occurs when a person starts at a stationary pinpoint of light located at a distance in a completely dark room. Most people will think that the light is moving around. This was the starting point of Sherif’s study. He put subjects in a laboratory setting and asked them (by themselves) to estimate how far the light moved. Subjects really had no way of guessing the correct answer and no frame of reference. From the subjects’ estimates, the researcher was able to determine a range of responses for each subject. [Note, in reality, the light is not moving]. Sherif then took three subjects into a room, and had them observe the light. Although these people had widely different estimates of the movement when they were alone, the estimates made in groups converged. The lack of an external set of information and being uncertain about one’s own judgment led individuals to use OTHERS’ estimates for defining reality. When the group of subjects was broken up, and the individuals observed the light by themselves several weeks later, their estimates of the movement distance echoed those made by the group. B. Majority Influence (or “why do we bend to the pressures of others”?) 1. Majority influence is the process by which a group’s majority pressures an individual to adopt a position on some issue. A classic study by Asch (1951, 1955, 1957 – 1970s replication shown in video clip) illustrates this principle. His studies were conducted with a sample of students at Haverford College. Using a laboratory setting, Asch set up a situation where an individual was surrounded by a majority that agreed unanimously on a factual matter (on the topic of size judgments), yet the group was obviously in factual error. In these studies, it was demonstrated that groups can pressure their members to change their judgments and conform with the majority’s position, even when that position itself is evidently wrong. 2. What did Asch do? In a typical experiment (recall that this experiment was replicated numerous times), a group of eight people was assembled. One person was a “real subject,” and the others were actors or confederates. An experimenter would show large cards displaying a “standard” line, and three comparison lines. The subject’s task was to decide which of the three comparison lines was most similar in length to the “standard” line. One line was exactly the same length, one slightly shorter, one much shorter. During the experimental trial, each “subject” publicly announced which of the three lines best matched the “standard line.” The confederates all said their answers BEFORE the real subject, who replied last. This task was replicated 18 times, using different sets of lines (though with similar patterns). 3. What did Asch find? Across multiple trials, about one-third to one-half of the time, the “true” subject would comply with the majority - even though they were wrong. [In trials where subjects were simply asked to answer the question IN ABSENCE of confederates, fewer than 5% of answers were incorrect]. 4. How did the subjects explain their behavior? Asch interviewed his subjects following the experiment. Most were very aware of the fact that their judgments were at odds with the group’s. Most reported that they felt confused and under pressure, and were quickly trying to make sense of things in the lab setting. Some believed that maybe they misunderstood the experimenter’s instructions (perhaps name the line that is most different). Another theme that emerged was that the subjects engaged in “public compliance.” That is, they conformed to the majority opinion in public, yet in private still held on to their own views. C. Under What Conditions to People Conform? People conform MORE when 1. Size of majority increases. As the size of the majority increases, one’s tendency to comply increases. However, it is not a linear relationship. Rather, Asch found that conformity to unanimous false judgments increased with majority size up to three members, and remained fairly constant beyond that point. This finding has been replicated across numerous studies. The implication is that after majority contains more than three members, subjects believe that others are just “going along” with the group to avoid trouble and do not necessarily agree with the majority view. 2. They face a unanimous group consensus. Unanimous majorities are effective, and lack of unanimity reduces compliance. A person will be more likely to disagree if he or she sees that at least one other person has already disagreed. Why? It takes just one individual to offer support and validation for a dissenter. 3. They value or admire the group. People will conform more when they like their group, and want to be accepted by its members. Fear of rejection will make people conform. 4. They are committed to future interaction. Group members are more likely to form when they expect that their relationship with the group will persist in the long-term. 5. They have no prior commitment or belief. People conform LESS when 1. They have great confident in their expertise on the issue. Informational social influence is low. 2. They have high social status 3. They are strongly committed to their initial view 4. They do not like or respect the source of influence Personal characteristics that might impact compliance: 1. Gender? Theory on gender role socialization suggests that women may more likely to conform, given that girls are socialized to be agreeable and compliant. Eagly (1978) reviewed findings from 61 conformity studies, and found that women were slightly more likely to conform than men. She also found that men and women complied at equal rates in PRIVATE. It is only under public conditions that males tended to resist social influence. 2. Time period/culture: Are the Asch findings bound by culture or time period? Recall that Asch’s studies were primarily conducted in the 1950s, among college students. 1. Bond and Smith (1996) located 133 studies from 17 countries that used the Asch line-judgment task. They wanted to examine the results of these studies to see whether behavior has changed since the conformist 1950s. They also were interested in whether a culture is individualistic or collectivist had any impact on conformity behavior. An individualistic society is one such as the United States or western nations, which place central importance on individual achievement and personal goals. Collectivist societies such as Asian and African nations stress group goals. The researchers classified countries into one of these two categories, and contrasted results from the studies. They found greater conformity among the collectivist societies, and found that conformity has diminished since the 1950s. D. How do Groups React to Dissenters? Not all group members conform. Lack of conformity, or conflict in a group, can cause a group to disband or collapse. In order to avoid such an outcome, groups can generally take one of three paths to deal with a “deviant” or source of conflict in the group. 1. Apply pressure to make “deviant” conform. When the group recognizes that one of its members disagrees, the group will increase communication and try to persuade the deviant to conform. Strategies include reiterating the group’s goals to the deviant, and urging him/her to comply. This is perhaps the easiest approach; bringing the deviant back in line with the group’s majority. If that doesn’t work, the group may take a “harsher” approach. Strategies might include threats and punishments. 2. Reject the deviant from the group. If the majority cannot persuade the deviant to endorse their position, the other option is to reject the deviant. He/she might be expelled, or kicked out of the group - although this tactic might lower the morale and cohesion of the group as a whole. Status degradation can also occur; the person is relegated to a low status in the group. Psychological isolation may also occur; the person might be ignored and left out of communication. By rejecting the deviant, conformity and similarity in the group is enhanced.