Khanna B - anil k gupta blog

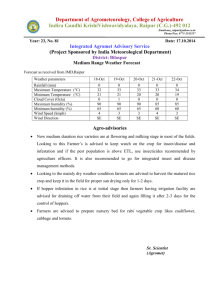

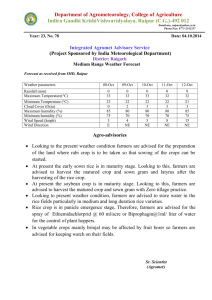

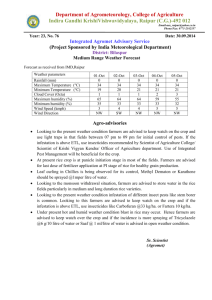

advertisement