The Role of Institutions in Economic Change

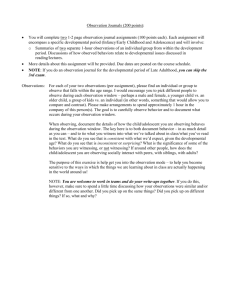

advertisement