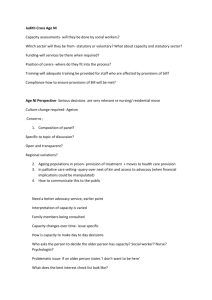

EEDIM Findings

advertisement