Arguing about Intervention - Open Research Exeter (ORE)

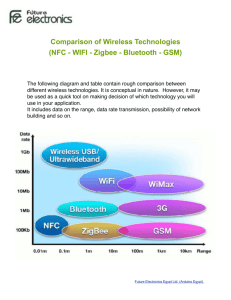

advertisement