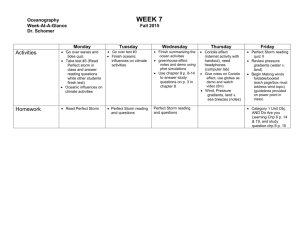

The Perfect Storm

advertisement

Apropos of our recent conversations about dangers in the present economy, I'm forwarding a NY Times article: Collectively we're walking blindfolded near the edge of a cliff... Not automatic disaster, but major risk. The key point is that the factors listed in the NYTimes article below are independent of the Peak Oil problem, and aggravate it, and like Peak Oil, will continue to worsen in the time horizon of 2005-2010. They are systemic weaknesses in the US economy--and all parts of the world economy closely tied to the US--that have been slowly worsening for 20 years. This can cause the same kind of stagflation that higher oil prices will. At the same time, either one can trigger the other, and worsen the other into crisis. As the article suggests without underlining it: any random financial system shock can bring down the US financial house of cards, because it can come from anywhere in the world, and then magnified by the US, echo around the world again to set off a major global financial crisis linked to systemic underlying problems that include ecology and resource wars and oil, etc. Selfprotective nervousness about the situation that tilts into spasmodic actions is what shocks unstable financial systems, and that worsens everything else. Bernard Lietaer has been talking about the instability of the global finance system for years... This is a major reason why corporations need to be resilient rather than just profit maximizers at this time. The kind of business to be in is whatever does well regardless of good times or bad. The worst kind of business to be in is what requires low interest rates, an up stock market, or lots of disposable income sloshing around. Whoever is debt leveraged is in trouble: consumers or businesses alike. This is also a major problem for any investment at all. Once upon a time, consumer investment in a house would buffer against instability of stocks and bonds, and in other financial instruments. Now the housing bubble confounds that. Even holding cash is no solution with stagflation. Some forms of real assets may be good investments, but not the standard ones. This article is similar to the kind of warnings that appeared before the stock market bubble burst: not trumpeted on the business page, but put into background analyses for the thoughtful, in places like The NY Times' News of the Week in Review. It was on the basis of this that I pulled all our money out of the stock market last time, about 9 months before the dot.com bubble burst. Timing is fundamentally unpredictable and random on these things, but the direction of it is obvious over a period of several years. This not only smells like all the recent financial crises that the author cites, but like 1929... And that is why the author calls it "a perfect storm" without saying "great depression." Can't have the NYT setting off a panic now, can we? Paul Ray Paul Ray spoke at OSS ’03, and is the co-author of Cultural Creatives. He may be one of the most capable observers of the US demographic & socio-economic scene. Below is the article to which he refers. Normally we would point to the link, but we refuse to subject our visitors to the nonsense associated with “registering” for online access. This is a very important piece of writing. It may be the single most important article you will read this year. Mr. Gross merits our intense attention, and the NYT our thanks, for publishing this. The Perfect Storm That Could Drown the Economy By DANIEL GROSS NY Times, May 8, 2005 WE seem to be living in apocalyptic times. On NBC's "Revelations," Bill Pullman and Natascha McElhone seek signs of the End of Days. In the Senate, gray-haired eminences speak of the "nuclear option." The doomsday theme is seeping into the normally circumspect world of economics. In April, Arjun Murti, a veteran analyst at the investment bank Goldman Sachs, warned that oil could "super-spike" to $105 a barrel. And increasingly, economists are prophesying that the American economy as a whole may be sailing into choppy waters. Just look at the many obvious and worrisome portents. The government each year spends much more than it brings in, and so the nation has a large budget deficit ($412 billion in fiscal 2004, and growing). Americans also import far more goods than they export, and so the nation has record trade and current account deficits. As consumers, Americans personally spend significantly more than they earn. Worse, some imbalances are eerily reminiscent of conditions that helped touch off recent economic crises: Mexico in 1994, Asia in 1997, Russia in 1998 and Argentina in 2002. Throw in rising interest rates, warnings of a housing bubble and the potential for higher inflation and slower growth (a k a stagflation) - and you can understand why some economic analysts may be plumbing the New Testament for inspiration. The forces propelling and buffeting the economy are like a series of interrelated and interconnected weather systems. Could they be setting the conditions for a perfect storm - a swift series of disturbances that causes lasting damage? If so, what would it look like? "There's a pattern that is familiar from so many other countries that have gotten into debt problems," said Jeffrey A. Frankel, an economist at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. "A simultaneous rise in interest rates, fall in securities prices and depreciation of the currency." Of course, economists, always armed with bandoliers of caveats, are quick to warn that the economy is relatively healthy. Job growth numbers released on Friday were strong, with 274,000 new jobs created in April. And they warn against drawing parallels too sharply between the mighty United States and emerging markets. The dollar remains the world's reserve currency, and the United States is a global military and political hegemon. And the nation has been able to borrow huge amounts for years without suffering a crisis. That said, how might a perfect storm be created? It would likely gather overseas, and wouldn't necessarily take the form of a terrorist strike or oil shock. The United States finances its spendthrift ways by selling dollars and dollar-denominated securities (like Treasury bills) to foreign creditors, mostly to central banks in Asia. To sustain growth, the United States needs foreign creditors to continue to add to their piles every day. Any signs to the contrary are worrisome. In February, when the Korean government suggested that the Bank of Korea might diversify its foreign exchange holdings, "this seemingly innocuous statement set off a small panic in our stocks and bond markets," said James Grant, editor of Grant's Interest Rate Observer. If the Bank of China, which has been accumulating dollars at the rate of $200 billion a year, decides to cut back on new purchases, either to diversify or to let its currency appreciate, the United States would quickly have to offer sharply higher interest rates to retain existing investors and entice new ones. Nouriel Roubini, an economics professor at New York University's Stern School of Business, estimates that if China cut its rate of accumulation by half, long-term interest rates in the United States could rise by 200 basis points over a few months and the value of the dollar would fall. Such a rising tide - the yield on the 10-year bond shooting from 4.25 to 6.25, the average 30-year mortgage rising from 6 percent to 8 percent - would mean instantly higher borrowing costs for the government, businesses and consumers. It would drench Wall Street, soaking the stocks of giant interest-rate-sensitive blue chips like Citigroup and making life difficult for speculative, debtridden companies. Some highly leveraged hedge funds or investment banks caught on the wrong side of trades would incur significant losses. The United States weathered a sharp decline in the stock market just a few years ago, in large part because of the housing market's strength. But a sharp rise in interest rates would literally hit home. For new home buyers, or for people with adjustable rate mortgages, 200 extra basis points of interest on a $400,000 mortgage would represent $8,000 a year in extra payments. If mortgage rates were to rise sharply, housing prices would level off and perhaps do the unthinkable: fall. Suddenly, the mechanisms that have allowed consumers to keep the economy afloat - the ability to realize profits from selling homes, to refinance mortgages at lower rates and to borrow cheaply against home equity - would be broken. In the absence of sharply rising wages, that $8,000 in extra interest would be $8,000 less to spend at Home Depot, or at the Cheesecake Factory, or at Disney World. "Personal expenditures in the past 15 months have been largely financed by borrowing," said Wynne Godley, a Cambridge University economist who is affiliated with the Levy Institute at Bard College. "And even a reduction in the pace of debt creation will force people to start spending less, on a big scale." If the dollar weakens and consumption falls, the trade and current account deficits would start to narrow. But the United States economy would slow and, perhaps, even shrink. "The result would not be a full-blown financial crisis most likely, but it would still be a major recession," said Barry Eichengreen, a professor of economics and political science at the University of California at Berkeley. What would create the full-blown crisis? When the slowdown starts to radiate across the globe, said Catherine L. Mann, senior fellow at the Washington-based Institute for International Economics. For years, the American consumer has been the engine of global growth, by gobbling up the output of oil wells in Saudi Arabia and factories from Mexico to China. "The slowdown in consumer spending is going to have a negative influence on the global economy through reduced international trade," Ms. Mann said. What's more, a recovery would be comparatively slow in coming. When the global economy came to a screeching, synchronous halt in 2001, the United States led much of the world back to growth because the federal government went on a stimulus binge for several years: Congress significantly increased government spending while cutting taxes, and the Federal Reserve slashed interest rates to historic lows, and held them there. But in the perfect economic storm, none of these three powerful levers would be readily available. Today's deep budget deficits make both significant tax cuts and spending increases unlikely. And rising interest rates would make it difficult, if not impossible, for the Federal Reserve to reduce the cost of borrowing. It sure sounds alarming. But as the clouds gather and the wind stiffens, we sail onward, with no apparent adjustment in course, full steam ahead. Why aren't we rushing to take evasive action? Why is Congress adding new spending while it passes new tax cuts? Why aren't financial institutions encouraging Americans to pay down their debt rather take on more? A lot of it has to do with timing. While many economists are willing to imagine in detail what a perfect storm would look like, virtually none will forecast precisely when - or if - it will start. And so it remains a vague and distant possibility. Besides, adds Jeffrey Frankel, "some of us have been warning of this hard-landing scenario for more than 20 years."