Banners of the British Labour Movement

advertisement

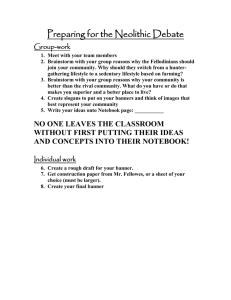

Banners of the British Labour Movement By Dr Myna Trustram There is a crowd of chanting people walking down the street, traffic is at a standstill and police line the pavements. How do you know who these people are and what they want? Whether you lived 150 years ago, or today, it's their banners that tell you. Introduction For hundreds of years, organisations that have a marching tradition have made banners in order to identify themselves. This includes trade unions, friendly societies, temperance groups, co-operative societies, Orange orders, suffrage, women's and peace organisations and political parties, but also non-political organisations like churches, chapels and Sunday schools. Political organisations that did not have a tradition of processions, like for instance the Anti Corn Law League or the anti-slavery movement, did not produce banners. Historians can 'read' banners for evidence in much the same way as documents. The origins of political banners 'Historians can 'read' banners for evidence in much the same way as documents.' Strangely enough, the origins of nineteenth and twentieth century banners can be traced to a time when organisations were concerned not to be identified. The precursors of trade unions were the trade societies. In the eighteenth century, when industrialisation was beginning to make an impact, trade societies were established to protect the interests of skilled artisans. Until the repeal of the 1799 Combination Act in 1825, membership of trade societies was illegal. Highly ritualised secret meetings were held in pub rooms where, amongst other items of regalia, textiles demonstrated the trade's ancient and respectable past. One of the few surviving textiles from this period is that of the Loyal United Free Mechanics. It contains elements that became standard in thousands of trade union banners later in the century: Old Testament scenes and Masonic symbols, but also the linked hands of friendship and unity. Besides trade societies, popular reformist groups from the 1790s used banners, although none survive from this early period. Just one banner from the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 exists today. We know of some 24 surviving banners associated with the Reform Crisis of 1829 - 1832. The plumbers' reform banner probably started as a small wall hanging before being sewn onto a larger fabric with the addition of a painted slogan to celebrate the Reform Act of 1832. Eighteen of the surviving reform banners are Scottish. Banners were used in elections both before and after the Reform Act. We know of 28 surviving election banners that are fairly evenly divided between Whig and Tory. These banners are elaborate constructions, mostly painted on silk and confirm the view that large sums were spent on electioneering. Unfortunately, there are no surviving Chartist banners, even though it is likely thousands were made. Trade union banners The banners with which we are most familiar today are those of the mass trade union movement. The trade societies evolved into the skilled workers' New Model Unions of the 1850s onwards. These unions' banners retained many of the same elements, such as the tools and processes of the trade, of the earlier trade societies. The 1889 Great Dock Strike brought about a surge in union membership from unskilled workers and a great demand for banners. Some were made by union members or sign-writers, but unions which could afford to do so turned to the firm of George Tutill. 'The 1889 Great Dock Strike brought about a surge in union membership from unskilled workers and a great demand for banners.' Tutill started making banners in 1837 and developed the technique of oil painted, double-sided silk banners which dominated designs for one and a half centuries. The banners would typically depict the benefits that could accrue from union membership (such as widows' pensions), the dignity of the trade, brotherhood, unity and justice. The latter was rarely couched as a demand, but as a reasoned request. The banners easily perished, from being battered on marches or being stored in damp, cramped conditions, so few banners survive from the late nineteenth century, although there are significant numbers of surviving friendly society banners. Their high survival rate can perhaps partly be explained by the central importance of public pageantry to the life of friendly societies. Women's suffrage banners The women's suffrage movement was a large-scale propaganda campaign that relied heavily on processions and printed material to convey its message. Banners were used extensively. Unlike trade union banners, suffrage banners were embroidered, stencilled or appliquéd and were created from within the movement. Women's traditional needlework skills were employed in a collective and creative endeavour. Some 150 banners were produced between 1908 and 1913, many by the Artists' Suffrage League. The designs were heavily influenced by the arts and crafts movement and were much smaller and simpler than trade union banners. Twentieth century banners 'The use of banners grew during the 1890s and reached its peak in the years after the First World War.' The use of banners grew during the 1890s and reached its peak in the years after the First World War. Following the slump of 1921 they declined, a decline that simply paralleled the ups and downs of the labour movement. The movement's fortunes peaked again in 1945 with the post-war Labour government but then declined further. There was a resurgence in the 1980s with anti-Conservative government activity. Regardless of the rise and fall of the labour movement, banners were regularly paraded at the annual miners' picnic in Northumberland and the miners' gala in Durham. These were political and family festivals where banners were proudly displayed, but as pits began to close from the 1960s the numbers of banners began to dwindle. In the early twentieth century banner makers adopted some of the imagery of the socialist artist, Walter Crane. Typically, workers were invoked to pursue socialism by a classical female figure beckoning them to a golden future of emancipation. But despite this innovation, the standard trade union banner in the 1930s looked much the same as it did in the 1890s. In the second half of the twentieth century banners were made of a variety of materials. Those based on nineteenth-century forms were still produced, along with artist-designed ones and the cheap availability of fabric, paint and glue meant that many were home made. The National Association of Local Government Officers banner illustrates how today's trade union banners retain common elements with the designs of Tutill, but use different materials and techniques. What do banners tell us? Banners are much more than simple expressions of a movement's identity or aspirations. Some are intriguing and many require a multi-layered interpretation of history rather than a simple narrative. It is easy, for instance, to see them as proud symbols of protest, but they can also reveal great conformity. Suffrage banners displayed women's traditional needlework skills and yet their purpose was to undermine the conventional view of women. Why has the design of the Northumberland miners' banners not changed over 170 years? Why do many 'radical' banners of the early nineteenth century contain the union jack? In attempting to answer the latter question, Nick Mansfield argues that banners can be used to question E P Thompson's thesis of the essential radical nature of the working class in the early nineteenth century. Mansfield suggests that the use of union jacks by radicals is not surprising and that banners can be used to develop ideas on the many-stranded nature of working class radical politics at the time. '...banners can become the embodiment of an organisation, a potent symbol of beliefs and hopes for change.' It was due to Tutill's stranglehold on banner production that the basic design of the Northumberland miners' banners did not change. Tutill can be revered as the people's artist who presented the aspirations of many millions of working class people on their banners. Equally, he can be charged with simplifying the complexities of a vibrant movement into sentimentalised caricatures of noble workers and their families. But the constancy of their banner design also betrays the miners' profound identification with the past. And it is not just the miners that use their banners as reminders of their heroic past. The twentieth century London watermen and lightermen's banner, for example, pays tribute to the role of Cardinal Manning as a mediator in the Great Dock Strike of 1889. The reverse refers to the first Act of Parliament in 1514 to regulate fares upon the Thames. Like tattered military colours hanging in cathedrals, banners can become the embodiment of an organisation, a potent symbol of beliefs and hopes for change. The Tea Operatives and General Labourers Association banner was used throughout the Great Dock Strike and was later sewn onto silk and marked as 'The Original Banner'. Some banners can thus become icons. Find out more Books Follow the Banner: An Illustrated Catalogue of the Northumberland Miners' Banners by Hazel Edwards (Ashington, 1997) Banners of the Durham Coalfield by Norman Emery (Stroud, 1998) Banner Bright: an Illustrated History of Trade Union Banners by John Gorman (Essex, 1986) The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907 - 1914 by Lisa Tickner (1989) Places to visit Pump House: People's History Museum, Manchester. This houses the galleries of the National Museum of Labour History. The People's Story Museum, Edinburgh, and the People's Palace Museum, Glasgow These museums also have good collections of banners, some of them on display. About the author Dr Myna Trustram's publications include Women of the Regiment: Marriage and the Victorian Army (Cambridge University Press, 1984). For fifteen years she worked in museums of social history, including the National Museum of Labour History. She now works as a museum consultant.