2. HEARing Student Voices Project

advertisement

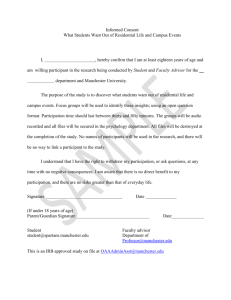

Self Portraits and Perpetual Motion: The Student Experience of Informed Choice and Feedback Jennifer BLAKE1 (Teaching and Learning Support Office, University of Manchester, UK) jennifer.blake@manchester.ac.uk Patricia CLIFT MARTIN (Teaching and Learning Support Office, University of Manchester, UK) - patricia.clift@manchester.ac.uk Louise WALMSLEY (Teaching and Learning Support Office, University of Manchester, UK) - louise.walmsley@manchester.ac.uk Valerie WASS (Keele Medical School, Keele University, UK) - v.j.wass@hfac.keele.ac.uk Abstract: With the goal of universal higher education and the growth in multiple careers for many there has been significant expansion in the skills and associated strategies that Universities must communicate to students, especially around the employability agenda (Cochrane & Straker, 2005, Ertl et al., 2008) Resources exist to facilitate informed choice but organization and presentation of resources is essential. Universities must understand which resources are most useful for students to avoid the “paralysis [that] is a consequence of having too many choices.” (Schwartz, 2005). This study uses focus groups and interviews with students in three disciplines with contrasting curricula structures and career paths to discover how students make informed choices, which resources they use and the utility of feedback and resources currently offered. Initial findings show that available resources need to be valid, verified and limited. The interaction between student and university can only be enriched by a deeper comprehension of choice processes and how resources and support can be positioned most effectively. (Foskett & Hemsley-Brown, 2001) This study will highlight resources that students feel contribute to informed choices and to discover what role students and university play in designing and validating resources. One resource available to students is academic feedback. Feedback can be used by students and faculty to inform choice and provide guidance and as an opportunity for students to develop a sense of their strengths and weaknesses (Hounsell, McCune, Hounsell, & Litjens, 2008). If students are to form portraits of themselves as learners then self-awareness and the ability to recognize aspects of their abilities are essential. Through integrating effective feedback the portrait they develop becomes more accurate. This paper will report on initial findings with regard to the student experience of feedback structures, and its impact on their learning. This research has implications for student learning styles, resource creation, and the use of feedback as a tool students can use to become an active contributor to the learning process. Keywords: Feedback, choice, student, informed, resources 1. Introduction The HEARing Student Voices project is a two-year research project funded by the Higher Education Academy as part of the National Teaching Fellowship Scheme Projects (The 1 Address for correspondence: Jennifer Blake, Teaching and Learning Support Office, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, United Kingdom (phone: 0044 1613061553) 15 Higher Education Academy, 2010). All projects funded through this scheme have the involvement of a National Teaching Fellow and have been through a rigorous two-stage bidding process. This project was developed in response to other initiatives nationally and institutionally at the University of Manchester where the project is based. Manchester is the UK’s largest single site university with over 27,000 undergraduates, nearly 10,000 postgraduates and more than 5,800 academic and research staff. There are more than 500 degree programmes encompassing a wide range of disciplines from Art History to Zoology grouped across 22 schools in four faculties. Although there are many resources available to students to help them navigate the curriculum including tutors, websites, peers, course handbooks and careers guidance, we know little about what they are actually using and what makes the resources that they use useful and valid. Since 2005, a National Student Survey has been conducted across all universities in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and some in Scotland. The survey is open to all final year undergraduates and asks questions on a range of issues around the student experience, primarily related to their programme and overall satisfaction. One of the areas which is analysed through the survey is ‘assessment and feedback’. In many universities, especially larger ones, this is a weaker area and more work needs to be done to develop a better understanding between staff and students of the assessment process and the opportunities for receiving and using feedback. In 2007 the University of Manchester embarked on a Review of Undergraduate Education to address these issues. The review encompassed all areas of the student experience from admissions to graduation. One of the recommendations from the Review Task Forces was that the University should be at the forefront of developments surrounding a new national initiative, the Higher Education Achievement Report. The Higher Education Achievement Report (HEAR) is a UK national initiative currently in the second phase of institutional trials. The HEAR developed from the work of the Burgess Group which was tasked with determining whether the UK degree classification model was broadly fit for purpose, and if there were any changes that needed to be made. The group concluded that the degree classification was fit for purpose but that additional information on 15 the achievement of students over and above the classification and the transcript would be of benefit to students, employers, and postgraduate admissions tutors (Universities UK, 2007). Building on the prior implementation of the European Diploma Supplement (EDS) (European Commission, 2009) the Group proposed that a document be produced which encompassed the EDS requirements but also gave a broader picture of an individual’s achievement within higher education. This document became known as the Higher Education Achievement Report. The main features of the report that differ from the EDS are an increased level of detail in the academic transcript information, (thesis or project titles, placement information etc) and considerably more information on extra-curricular activities such as volunteering, roles and responsibilities, prizes and awards, and additional training. Although the HEAR was originally described as a summative document to give additional information over and above the final grades of a student there has been an increasing movement to use the HEAR as a developmental resource to support the academic, personal and career development of students whilst on their course of study. To this end the University of Manchester is also pursuing the production of a formative HEAR which will likely take the form of an extract from the HEAR data-set and will be presented to students and available to their academic tutors. This formative HEAR will be informed by this research project to ensure it meets student needs and enhances the educational process. 2. HEARing Student Voices Project Throughout their studies students make choices about the academic and non-academic activities that they engage in. Many of these activities support their personal and professional development and help them achieve their career goals in an increasingly competitive job market. We were faced with two dilemmas: How do students across a range of different curricula make career choices and what is the optimum form of feedback which can most usefully support the development of the HEAR format. The project aims to research how: ● Students make educational choices within differently structured curricula ● Employment aspirations influence choice 15 ● The HEAR can best be designed to meet student needs ● Formative student assessment can influence career development. Our initial questions are: ● What factors influence student choice of units within the curriculum and what are their preferences for feedback? ● How can a HEAR be best constructed to inform choice and maximise use of feedback? Phase 1 of the project consists of focus groups and interviews with students and staff with structured questions on defining and making choices, the resources that are used or required for making informed choices, and on defining and using feedback. A better understanding of how students navigate through different contrasting curricula will enhance our approach to curriculum design and development and how we support and advise students as they learn. This phase of the project will be completed by summer 2010. Phase 2: In this phase of the project students and staff will engage in facilitated action research to explore different models for the presentation and content of a formative HEAR and how it might be used to inform student choices. The results of this project will inform the way the University of Manchester implements the formative HEAR and will be widely disseminated to inform practice at other universities. This paper focuses on the methodology and framework of Phase 1 of this project. At this time the results are still being analysed therefore only brief findings are presented. 3. Literature Review Higher education in the UK has seen a great deal of change in the last decade. With the massification of higher education, and the decline of the idea of one job for life, the skills and strategies universities must make explicit to their students have multiplied (Cochrane & Straker, 2005). The economic crisis, and consequent impact on employment, is a pressing issue for those preparing for or currently in the job market. All of these concerns have career and educational implications and the employability agenda is one that requires universities to work toward developing the autonomous learner with transferable skills (Ertl et al., 2008). 15 However, although it has been recognized that students face increasing pressures to exhibit reflective thinking skills, thoughtful decision-making and the habits of a life long learner (Gosling, 2003), comparatively little research has been done to explore the resources that students use to “navigate” the curriculum and to make career choices through which they develop these skills. Although a number of studies have looked into the motivation behind the choices students make (Breen, 1999; Young, 2000) relatively few have delved into the process that lies behind, and informs the choices—or whether students could be said to be making any sort of “informed” choice at all. It was evident in at least one study that students were taking the “path of least resistance” in their decision-making and that there was very little forward-planning (Cochrane & Straker, 2005). This lack of method in decision-making has further implications because, although “motivation is a hypothetical construct inferred from and indirectly based on an individual’s behaviour” (Curasi & Burkhalter, 2009, p. 4), and students in different disciplines may describe different motivations for their choices (Breen & Lindsay, 2002), understanding the processes making informed choices could benefit all disciplines. The nature of the discipline with regard to curriculum structure, professional outcomes and available support, and the culture of the learning environment may have a significant impact on the mechanics of student choices as both the goals and the structure of support offered by degree programmes can vary widely. Understanding how students use resources to make decisions could also be used to inform and enrich personal development planning. As one of the goals of personal development planning is to highlight and hone the “meta-skills in reflection and self-direction” (O'Connell, 2003, p.17 ), better knowledge of the resources that students are currently using could be used to inform meetings with academic advisors, who provide students with academic development advice within their discipline. One of the resources available to university students is feedback. Feedback, both formative and summative, can be used by students and staff as tools for choice and guidance. (Hounsell et. al., 2008). However, to be useful, the feedback must not simply be “constructive and timely” but also assist students to identify areas of improvement and set in place action plans to achieve this; in effect, feedback must not merely justify the mark, but encourage further learning as well (Hounsell et al., 2008; Pitts, 2005). The concept of a feedback loop, which includes the student, advisors, lecturers, 15 and others, and constantly informs and clarifies, could help lighten the burden on the student to be the one to assimilate and understand all of the feedback he or she receives. Understanding the places students go to for information could help to make the formative HEAR and other feedback more student relevant and help ensure that it is used to help inform future decisions. In looking at how students navigate their choices in curricula, we will be able to devise better tools, like the formative HEAR, to help them. In their literature review of the student experience, Ertl et al. (2008) find that there is a “need to go beyond ‘information transmission’ where students are in passive mode, to involve students actively.” (p. 9). Looking at what resources students use will help maximize the dialogue between teachers and students and, hopefully, help feedback and other assessment feel like less of a bureaucratic process and more a part of student learning (Ertl et al., 2008). 4. Study Methodology Using focus groups in this study allows us to make the student learning experience the centre of the study and to carefully investigate vocabulary and language use. There was also potential for engagement in the focus groups to foster interest in the Phase 2 action research. We decided to use qualitative methods in this study because the possibilities of in-depth narrative investigation because it was thought that the narrative possibilities of focus groups and interviews would allow us to explore the definitions and culture surrounding choice, feedback, and resources and build theoretical frameworks on which to enhance our understanding of student approaches to navigating the curriculum and reaching appropriate career choices. The qualitative nature of the project also allows us to explore the individual differences and definitions of these topics. Focus groups generate primarily qualitative data and serve as records of the individual members of the group and also of the interactions and reactions of the group as a whole, thus providing a unique snapshot of group opinions and discussions while allowing for individual differences. It is in this way that focus groups differ from the broader category of “group interview” as the focus groups deliberately take into account ‘the explicit use of group interaction’ (Merton, 1987). This emphasis also clearly separates it from individual interviews as the focus group data is equally dependent on the interactions between the participants (Cronin, 2002). 15 The decision to add interviews in addition to the focus group was taken in order to triangulate the data that had previously been gathered and to ensure saturation of themes. It was felt that the in-depth nature of the interviews might allow for deeper understanding of the context of the data. In addition, as is stated below, recruitment was an issue, and additional interviews were scheduled where recruitment for the focus groups was difficult. Julius Sim (1998) mentions a number of advantages to focus groups including being an economical way of interviewing a number of different respondents, providing information on the dynamics of a group, encouraging spontaneity, possibly providing a ‘safe’ forum as respondents may not feel pressured to answer every question, and the opportunity for the participants of feel supported by a ‘sense of group membership’ (Sim, 1998). This is valuable to the researcher for a number of reasons, not least of which is the chance to observe a discussion on the underlying assumptions that form the culture of the group being studied. In this study, it means that the students, staff and their experiences are the central reference points for analysis. We focused on three contrasting curricula within the University of Manchester with structures which potentially impact differently on student choice: (a) Pharmacy: a highly structured programme with a definite career outcome; (b) BA/BSc Geography: a large honours degree programme with a medium level of structure around a mix of core and optional units with no definite career outcome; and (c) BA English, a relatively unstructured honours degree programme with a wide choice of units and no compulsory final year units other than a dissertation. By choosing these contrasting programmes we aim to explore the self-directed learning needs of a diverse range of students in contrasting learning environments and ensure that the findings are generalisable across different curricula structures. As a first step, questions were formulated from the literature review and piloted with a group of ten second, third, and fourth year students from different disciplines, drawn from students who have already worked with the Teaching and Learning Support Office. This exploratory group met once for 80 minutes. The meeting was recorded, transcribed and cross checked against the literature to ensure that all relevant areas were covered by the question set. After the pilot focus group, only very minor changes were made to the questions (Appendix 1). 15 Recruitment of student volunteers for the focus groups and individual interviews was done through email recruitment and general information sessions. This method was problematic as the response rate was not high, and it is possible that the participants were self-selecting from strongly motivated students therefore an effort was made to discover whether or not the experiences described by the participants were “typical” experiences in the degree programme. In addition, where response rates for the focus groups were especially low, further individual interviews were scheduled in an effort to get a better picture of the degree programme. After the recruitment process, the first focus groups of students were formed in curricula groups. Focus groups can range from four to twelve participants. Traditionally, between six and ten people have been considered “ideal”, but there has been some discussion that smaller groups of four to six can be of benefit as they allow for greater exploration of the individual opinions and stories within the group (Cronin, 2002; Munday, 2006). These groups met two times for 80 minutes each. A summary of participant numbers is included as Table 1. There was a disparity between disciplines in recruitment to focus groups with lower participation from English Literature. It is possible that the difficulty in recruitment stems partly from the amorphous and relatively unstructured nature of the English Literature degree programme. As there are no required units or entire-year meetings recruitment information sessions were done by visiting individual units so the whole year group may not have been aware of the opportunity. For the second set of focus groups new participants were recruited and mixed focus groups covering the three disciplines were set up with the hypothesis that giving the participants an opportunity to compare experiences would allow for more general discussion on resources necessary for all students, instead of discipline specific issues. It was hoped that the discussion between disciplines would highlight any differences in the definitions of informed choice and feedback and elicit further community definitions and realities. Enough students were recruited to run two mixed discipline focus groups. Again, it was most difficult to recruit from the English degree programme, and it was decided that additional individual interviews would be sought to attempt to balance the data. 15 Table 1:University of Manchester Participant Numbers (at May 2010) Pure Mixed Discipline Mixed Discipline Discipline 1 2 Geography 8 2 2 3 scheduled 15 English 4 3 3 5 15 Literature Pharmacy Interviews Discipline totals completed 10 2 4 3 19 completed 22 7 6 11 49 We expanded the study beyond Manchester and scheduled three focus groups at Northumbria University in Newcastle, England. Groups were scheduled with Social Work, English Literature, and Geography students. Northumbria does not offer Pharmacy therefore Social Work was chosen as it is highly structured, leads to professional accreditation, and involves placements away from the University. Students were recruited by a colleague from Northumbria. There was an excellent response from the Social Work participants, but, once again, there was difficulty in recruiting English Literature participants, and there were additional issues with Geography recruitment. These problems could be attributed to the tightness of the scheduling of the groups, which interfered with some course meeting times. In addition, because the project had not been begun at Northumbria, there was not the same level of preparation of staff and students as at Manchester, something that could also have contributed to the issues with recruitment. The study began with the creation of the questions for the focus groups. These questions were designed to be conversational and purposefully structured to encourage the sharing of personal stories. They began with a general opening question designed to introduce members of the group to one another and identify their names and voices for use on the audio recording. After the opening question, the study followed Krueger’s suggested sequence of introductory, transition, key, and ending questions (Krueger, 1998). These questions are designed to allow the participants to begin by exploring the topics under discussion and creating a shared vocabulary for the rest of the meeting. This community definition was key in the exploration of topics such as feedback, as it became clear that establishing common definitions of these elements allowed the participants to discuss wider implications and explore meaning. Each topic (choice, feedback, career plans) was treated as its own question 15 section with an introductory, a key question, several transition/follow up questions, and one ending question per topic. Additionally, attention was paid to the final questions to prompt discussion of what a “typical” experience might be in each degree programme in order to establish whether any of the participants felt as if their experience had been outside the norm for any reason. 4.1 Analysis methods The main qualitative analysis methodology used is a constructivist form of grounded theory, using pre-existing theory to provide ‘sensitising concepts’ (Bowen, 2008), whilst using purposive, iterative sampling and constant comparative analysis to arrive at trustworthy conclusions. The project is conceptually orientated towards social learning theory which interprets learning in terms of the interaction between the individual and the social milieu within which they learn, emphasising learner empowerment and development of a sense of self efficacy (Salomen & Perkins, 1998). The decision was taken to use grounded theory to search out a complete picture of the interactions between the participants, the cultures of the different curricula, and the realities of choice, feedback, and career planning. As the results are so dependent on the participants’ own experiences, it was thought that the grounded theory methodology would allow for the greatest scope in analysis. The focus groups and interviews were transcribed indicating any lengthy pauses or conversation fillers as well as everything said. Once transcribed, Nvivo, a qualitative data analysis program, was used to code and sort the data. Because Nvivo allows for multiple codes to be applied to text blocks of different sizes (from single letters or words to entire paragraphs or transcripts) it is possible to explore the data in a number of ways. We used codes as a method for developing the themes that were coming out of the transcript data. We used additional codes to indicate the speaker, the specifics of the focus group (mixed/discipline pure), and the question group prompting the specific discussion. This particular code provided important as it became apparent that the question path was working to facilitate the answers the participants were giving. 4.2 Emergent findings The focus group method fits neatly into this project because of its ability to be both flexible and deliberately planned. Because the questions allowed for a wide range of responses, we 15 were able to ensure that each of the participants had a chance to “practise” contributing with a definition before being asked to share stories or personal opinions. It allowed for a sense of community to build which then supported more in depth and frank discussion on improving feedback and enhancing resources. The addition of individual interviews allowed us to triangulate the data gathered in the focus groups and make contact with students that were unwilling to participate in the group setting. The set-up of the questions allowed investigation into the differences between the ideal situation with choice and feedback and the reality, both in the resources available and the students’ use of those resources. The flow of the questions and the focus group as a safe space allows a discussion of what could be a heated subject to change focus and become more an exercise in community building—because it is not just participants demanding the ideal but a discussion of the reality on both sides. The questions were designed to first establish a common definition of the topic under consideration. For example, the first question asked about informed choice is: “When you hear the words ‘informed choice’, what comes to mind?” This prompted a range of definitions from a choice where one has spent time “considering all the different options, seeing all the different sides” to where “someone has sat down with you and has given you some information.” The follow up question, which invited participants to begin thinking about themselves by asking “Do you feel able to make informed choices?” also prompted most to claim that they do/have made informed choices in their lives (occasionally with some frequency). However, while most answered in the affirmative when asked whether they felt able to make informed choices, when asked, in the next question, to tell the story of a recent choice they had made in their degree programme, most described that curricula choices (i.e. choices on units and essays) were often made from little information or by “shooting in the dark” as opposed to real informed choice. These differences allowed the participants to further refine their original definitions of, in this case, informed choice. The result was a list of resources that participants felt they needed to access in order to make these choices. This change in the discussion changed the focus of the analysis because it implied that, although informed choices are often defined as something made independently, the availability and ease of use of the resources participants needed to make informed choices were clearly important. 15 In the case of feedback, a similar questioning path was created. When the definition of feedback was requested, many participants described a situation where feedback would be used to improve or change methods of work or choices in the future. However, when the follow up questions were asked in order to prompt specific stories about use of feedback, it became clear that the abstract definition of feedback and the concrete examples illustrated a disconnect between definition and real life use. This process of discussion allowed the students to establish a group definition, almost a definition of an “ideal” format and response to feedback that could be used as a springboard for discussions of the reality of feedback and what is needed for useful feedback. The effort to create group definition of the topics in the study also allows for fruitful cross group comparison. As the terms have been explicitly defined, it allows for more effective comparisons across the various focus groups, both where the groups agree and, perhaps more interestingly, where they disagree (Hounsell et al., 2008; Morgan & Krueger, 1993). The progression from abstract definition to concrete personal story creates a rich seam of data to draw from, especially in areas such as feedback and choice where implications of the differences between the community declaration and actual practice are telling. For example, a number of students stated positively that they used feedback to improve their learning but very few were able to give a concrete example. Originally it was our intent to use the data to create a formative document (termed the formative HEAR) to help with independent choice and career-planning. However, it became clear through the focus groups that the document would be better placed to work as a formative feedback document. In these cases, the feedback “loop” was being treated as if it were a perpetual motion machine, as something that needed no input beyond the original dissemination of the feedback. The participants reported feedback that rarely went beyond a specific assignment or unit and difficulty with blending feedback from a variety of sources, all of which would interfere with the “loop” that enables students to take on feedback and use it to inform choices and further studies. This difficulty synthesizing feedback also led to discussions about personal development and some aspects of the community in each degree programme. Students often mention wishing that there was a more personal relationship with some member of staff that would allow them 15 to feel comfortable seeking help with issues such as understanding feedback from courses. This situation is analogous to a painter creating a self portrait, where the use of a mirror actually creates a reverse image of the reality. As the students are working alone, it is difficult for them to assimilate and synthesize the variety of feedback they receive and create and complete and accurate picture. These issues are complicated by a nexus of militating factors that is often vague, leaving students with no clear map to indicate how they should go about learning or even searching for help. There are also implications about the learning environment present in each degree programme, something we hope to investigate further. These results are all extremely preliminary, but indications for improvement in practice and further investigation into feedback, choice, and resources are clear. A clear message is emerging that feedback and/or a HEAR framework alone is not enough. Students appear to need support in responding to and harnessing feedback to help them synthesise this into meaningful learning action plans or career development. 5. Further research 5.1 Phase 2 Plans Of particular interest to this study is the use of focus groups as a component of, or preparation for, an action research project. As action research requires engagement of participants in working towards a product or change, focus groups are valuable because of their potential to engage the participants in the research (Chiu, 2003). Focus groups (partially because of the previously mentioned possibility of a ‘safe space’) frequently seem an appropriate method for investigating topics that could be sensitive or embarrassing for the participants (Kitzinger, 1994). This encouragement of openness and discussion can have a powerful impact on informing the rest of the action research project as participant engagement can have a dramatic impact on the success of the research. Focus groups can also serve as opportunities for transmission of knowledge within a group, helping to make sure all of the participants in the action research segment of the project begin with a complete understanding of the issues being addressed and with a sense of ownership of the topics being discussed and the solutions or changes being proposed. With this in mind, beginning an action research project with a series of focus groups not only allows the researcher to gather pertinent data for the formation of the rest of the project but also encourages the participants to actively engage in the entirety of the study. 15 Initial interest in the second phase of the study has been positive. Most students seem extremely interested in participating in the action research phase of the project. Students will be actively involved in the action research model used to construct, pilot and compare formats for the annual formative HEAR. An exploratory trial will be conducted to develop and compare formats for the formative HEAR. According to the Phase 1 findings, two or three alternative formative HEAR formats will be piloted. Different forms of assessment of the unit/programme content (self and/or peer, formative versus summative) will be explored in response to the Phase 1 findings. This will be developed with students to harness their beliefs and maximise use of the structures offered by the different curricula. Evaluation of the outcomes of the formative HEAR, i.e. level of self-awareness, progress in personal development and success of career management will be undertaken by the researcher. These participating students will receive personal written feedback on the findings and will be actively involved in the development of the final format for the formative HEAR which will hopefully be rolled out to all undergraduate students the following year. Student feedback throughout will be harnessed to ensure a student friendly HEAR is ultimately produced. 6. References Bowen, G. (2008). Grounded Theory and Sensitising Concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5, (3) 1-9. Breen, R. (1999). Academic research and student motivation. Studies in Higher Education, 24 (1). 75-93 Breen, R., & Lindsay, R. (2002). Different Disciplines Require Different Motivations for Student Success. Research in Higher Education, 43 (6), 693-725. Chiu, L. F. (2003). Transformation Potential of Focus Group Practice in Participatory Action Research. Action Research, 1, 165-183. Cochrane, M., & Straker, K. (2005). Secondary School Vocational Pathways: a critical analysis and evaluation. Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference. Cronin, A. (2002). Researching Social Life. London: Sage. Curasi, C. & Burkhalter, J. (2009). An Examination of the Motivation of Business University Students. Business Education Digest, 18 (Dec) 1-18. 15 Ertl, H., Hayward, G., Wright, S., Edwards, A., Lunt, I., Mills, D. & Yu, K. (2008). The Student Learning Experience in Higher Education: Literature Review Report for the Higher Education Academy. (H. E. Academy). European Commission, Education and Training (2009, June 3 rd) The Diploma Supplement. Retrieved April 21, 2010 from http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/doc1239_en.htm. Foskett, N., & Hemsley-Brown, J. (2001). Choosing futures: young people's decision-making in education, training, and careers markets. London Routledge/Falmer. Gosling, D. (Ed.). (2003). Personal Development Planning (Vol. 115). Birmingham Staff and Educational Development Association. Hounsell, D., McCune, V., Hounsell, J., & Litjens, J. (2008). The quality of guidance and feedback to students. Higher Education Research and Development, 27 (1), 13. Kitzinger, J. (1994). The methodology of Focus Groups: the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health & Illness, 16 (1). 104-121 Krueger, R. A. (1998). Developing Questions for Focus Groups (Vol. 3). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Merton, R. (1987). The focused interview and focus group: continuities and discontinuities. Public Opinion Quarterly, (51), 550-566. Morgan, D. L., & Krueger, R. A. (1993). When to use focus groups and why. Newbury Park: Sage. Munday, J. (2006). Identity in Focus: the Use of Focus Groups to Study the Construction of Collective Identity. Sociology, 40(1), 89-105. O'Connell, C. (2003). The Development of Recording Achievement in Higher Education: Models, Methods and Issues in Evaluation. In D. Gosling (Ed.), Personal Development Planning (Vol. 115, pp. 15-28). Birmingham: Staff and Educational Development Association. Pitts, S. (2005). Testing, Testing.... How do Students Use Written Feedback? Active Learning In Higher Education, 6 (3), 11 218-229. Salomen, G. & Perkins, D. (1998). Individual and Social Aspects of Learning. Review of Research into Higher Education, 23 (1), 1-24. Schwartz, B. (2005). The Paradox of Choice, TEDTalks. Retrieved December 12, 2009 from http://www.ted.com/talks/barry_schwartz_on_the_paradox_of_choice.html. Sim, J. (1998). Collecting and analysing qualitative data: issues raised by the focus group. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28 (2), 345-352. The Higher Education Academy. (2010). National Teaching Fellowship Scheme (NTFS). Retrieved March 3, 2010 from http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/ourwork/supportingindividuals/ntfs. Universities UK (2007). Beyond the Degree Classification: Burgess Group Final Report. Retrieved (March 10, 2010)from: http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/Publications/Documents/Burgess_final.pdf Young, Z. E. (2000). Undergraduate choice and decision-making: why students choose Manchester. Sociology. Manchester, University of Manchester. Masters. 15 Appendix 1: Student Focus Group Questions These questions were approved by the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee. Opening Questions: ● Give us your name, where in Manchester you live, and one place where you enjoy going out for a meal. Focus Questions: When you hear the words “informed choice”, what comes to mind? ○ What makes you say that? ○ Do you feel you are able to make informed choices? ● Tell the story of the last curricula choice you made. ○ Do you make choices outside your curriculum that still affect it? ○ What sorts of extra-curricular choices do you make? ● What resources do you use to make curricula choices? ● What resources you need to make an informed curricula choice? ● Describe what you think of when you hear the words “feedback”. Do you ever use feedback from a prior event to make a choice? ○ What sort of choice was it? ○ How did you use the feedback? ○ Did you feel supported in your use of feedback? ● What would make feedback a more useful tool for choice? ● ● ● ● ● Where do you see yourself a year/two years after leaving university? Do you make curricula choices based on career goals? Do you feel your experiences are typical of someone in your degree programme? Closing: ● ● ● What resources do you wish were provided for you? Which of these is the most important? Is there anything we missed? 15