1 Cere The Problem of 'Nature' in Family Law Daniel Cere McGill

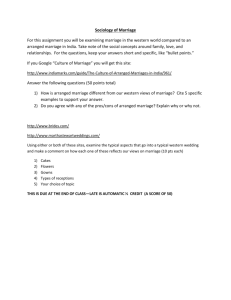

advertisement