Spring 1996

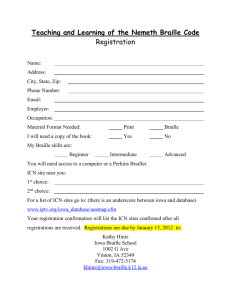

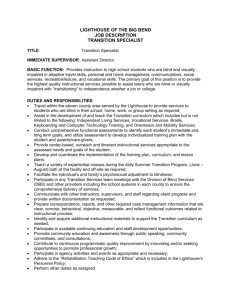

advertisement