workshop on bond market development

advertisement

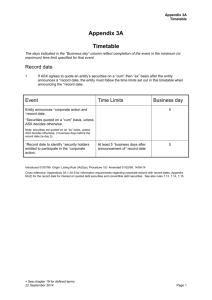

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (Central Bank of the Philippines) Country Paper for the SEACEN-World Bank Seminar on Strengthening the Development of Debt Securities Market I. Recent Development in the Domestic Debt Securities Market A. Objectives of Domestic Debt Securities Market Development Section 2 of the Securities Regulation Code (SRC) provides the State Policy as the objectives which the SRC is enacted to achieve: “The State shall establish a socially conscious, free market that regulates itself, encourage the widest participation of ownership in enterprises, enhance the democratization of wealth, promote the development of the capital market, protect investors, ensure full and fair disclosure about securities, minimize if not totally eliminate insider trading and other fraudulent or manipulative devices and practices which create distortions in the free market.” Meanwhile, under The Philippine Economic Plan of 2001, the Government realizes that the development of the capital market is critical to raising domestic savings that would finance investment growth. The Government endeavors to deepen the capital market through the elimination of taxes that serve as a disincentive to the development of the capital market, the development of asset-backed securitization, and the expansion of institutional players. B. Profile of Domestic Debt Securities Market The Philippines’ debt securities market is synonymous with the market for government securities since, over the past decade, public debt issues have captured over 90 percent of the market for debt instruments. Private bonds issues are rare, in part, because of stringent issuance requirements in the Corporate Code of the Philippines and also, to some extent, because of the absence of an organized venue for trading private debt securities. Domestic borrowing by the national government has always been among its major functions as a means to finance national development programs and to fill up gaps in its budgetary operations. Funding outlays could not be serviced entirely from tax revenues. Government expenditures, on the other hand, have risen in response to public policy measures designed to accelerate social and economic changes and in coping with mounting operational requirements. Public debt instruments had thus become the key vehicle through which the National Government and its instrumentalities broadened their financing base to meet manifold financial requirements. The then Central Bank of the Philippines had, since its inception in 1949, been in the forefront of the omnibus endeavor of issuing government securities. Republic Act 265 provides that the issue of securities representing obligations of the government, its political subdivisions or instrumentalities shall be made through the Central Bank which shall act as agent of and for the account of the Government or its respective subdivisions/instrumentalities. However, with the reorganization of the Central Bank, the fiscal agency functions had been gradually phased out and eventually transferred to the Department of Finance. 1 The variety of issuances that followed over the years had contributed to what has now become a broad spectrum of outstanding debt instruments consisting of bonds, notes, bills and certificates of indebtedness with divergent purposes, terms, conditions, utilities and other pertinent features. Since the formal issuance of government securities through the BSP following its creation in 1949, the yearly volume of primary sales had been in the uptrend from an initial float of P200.0 million to P1,832.491 billion in 2003. In direct proportion, outstanding government securities also grew significantly. (Please refer to Annex 1). For the years 1996 to 2003, the volume and value of transactions handled by the Bureau of Treasury pursued an uptrend, as shown below. The increased degree of public awareness and acceptance of government securities as well as the improvement of designs and types of government securities to conform to market specifications has contributed significantly to the increased secondary market trading. Year 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Volume of transactions n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 133,286 Value of transactions (in millions) Peso USD Equivalent 612,574.22 20,961.34 2,016,077.79 49,129.49 3,427,541.38 87,537.77 3,773,674.96 86,829.00 4,759,017.52 87,718.97 C. Credit Rating Agencies Increasing demand for ratings has evolved due to the array of benefits for issuers or rated institutions, investors, and intermediaries of organized credit rating agencies. The growing importance of credit rating agencies is a reflection of the increasing complexity of financial transactions. The benefits derived by market players from credit rating agencies include: For Issuers or Rated Institutions (Ratees) wider access to capital financing flexibility efficient new issuance improved counterparty relationships For Investors reduced uncertainty portfolio diversification risk premium assessment portfolio monitoring For Intermediaries facilitate pricing and underwriting monitor counterparty risk assist in capital allocation marketing 2 A credible and independent rating agency plays a critical role in the sound functioning of capital markets as it: provides investors with objective and unbiased opinions of relative credit risk which are essential tools for making sound investment and financing decisions; performs the functions of information search and monitoring, analysis and dissemination, and helps to level the playing field by providing transparency and disclosure to all investors of credit rated securities; maintains a continuously updated body of opinion on the credit quality of debt issuances and issuers; and undertakes market development and promotion work to popularize public debt securities. The Philippine Rating Services Corporation (PhilRatings) Previously known as CIBI Ratings, the Philippine Rating Service Corporation (PhilRatings) was part of the Credit Information Bureau, Inc. (now known as CIBI Foundation), set up in 1982 by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Central Bank of the Philippines, and the Financial Executives Institute of the Philippines. CIBI was organized to serve as a third-party, objective source of business and individual information. PhilRatings was spun off into a separate corporation in 1998. It remains a 100 percent-owned subsidiary of CIBI Foundation. It participates actively in the development of the Philippine capital market by implementing a national credit rating system. The BSP has approved the recognition of PhilRatings as a domestic credit rating agency (CRA) for bank supervisory purposes. PhilRatings is a founding member of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) Forum of Credit Rating Agencies (AFCRA). Set up in 1993, AFCRA was organized to enhance the effectiveness of credit rating agencies in the region and to help develop the ASEAN bond market. AFCRA regularly sponsors seminars and conferences to share experiences, enhance rating and risk assessment skills and to explore avenues of cooperation in keeping with the ASEAN spirit. PhilRatings is also a founding member of the Association of Credit Rating Agencies in Asia (ACRAA) set up in September 2001. SEC Credit Rating Requirement Securities which will be offered for sale to the public are required by the SEC to secure a credit rating from a qualified rating agency. Issuers are thus required to submit a credit rating report together with their registration statement, for purposes of evaluation and/or the guidance of investors. Moreover, issues being traded at the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) are similarly required to be periodically rated as the issue remains outstanding. Government issuances are exempt from this particular requirement. BSP Initiatives The introduction in the financial market of new and innovative products creates increasing demand for, and reliance on CRAs by the industry players, and regulators as well. As a matter of policy, the BSP wants to ensure that the reliance on credit ratings is not misplaced. In this connection, the BSP issued Circular No. 404 dated 19 September 2003, which outlined the rules and regulations that shall govern the recognition and derecognition of domestic credit rating agencies for bank supervisory purposes. Under the Circular, the BSP may officially recognize a credit rating agency provided that: (a) a domestic CRA is a duly registered company under the SEC; and (b) a domestic CRA must have at least five (5) years track record in the issuance of 3 reliable and credible ratings. The Circular put in place the minimum eligibility criteria for BSP recognition in terms of resources, objectivity, independence, transparency, disclosure requirements, credibility, and internal compliance procedure, as well as the grounds and procedure for derecognition. D. Developments in the Domestic Debt Securities Market The Philippine Government has renewed its efforts to spur the development of capital markets. The measures being proposed are expected to mobilize savings, introduce new financial instruments such as asset-backed securities and activate the secondary market. Over the past few months, several laws had already been enacted in addition to other measures that had been under taken to develop the securities market, among which are: a. The Special Purpose Vehicle Act of 2002 The Special Purpose Vehicle Act (SPVA) of 2002 was enacted into law on 23 December 2002 and became effective on 9 April 2003. (Please refer to the Asset-Backed Securities section below for a discussion on the SPV Law). b. Elimination of DST on Secondary-Traded Instruments. On 17 February, R.A. 9243, otherwise known as "An Act Rationalizing the Provisions on the Documentary Stamp Tax of the National Internal Revenue Code" was finally signed into law by President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. Specifically, the new law aims to: (1) eliminate the DST on secondary trading of debt instruments; and (2) establish a market environment conducive to the trading of financial instruments, so as to increase the volume of transactions in the secondary market. c. The Securitization Act of 2004 On 19 March, Republic Act No. 9627, otherwise known as the Securitization Act of 2004, was signed into law by the President. This sets the legal and regulatory framework for the sale of assets like loans, mortgages, receivables and other debt instruments as new securities to raise capital, thus creating a favorable market environment toward the development of the secondary market for these securitized assets. On one hand, the approval of the bill is expected to expand the menu of existing instruments available to investors and provide an avenue for portfolio diversification. On the other hand, it will generate more funds for both the private and government sectors, which can then be used for productive endeavors. d. Establishment by the Private Sector of the Fixed Income Exchange As early as 2001, the Bankers Association of the Philippines (BAP) was already planning to put up an exchange to centralize market transactions for fixed-income securities. This would provide the platform for the secondary trading of private and public fixed-income securities such as government securities, commercial papers and asset-backed securities issued by companies. The plan was supported by the BSP and the SEC as a way of providing the public with more investment options apart from traditional equities while, at the same time, opening up more avenues for the private and public sector issuers to tap low-cost capital. Initially capitalized at P500 million, major investors to the local bond exchange include the Philippine Stock Exchange,1 The PSE’s investment came about following the conversion of 32 percent of its stake in the Philippine Central Depository (valued at around P60 million) into approximately 12 percent of that of the new bond exchange. 1 4 the Development Bank of the Philippines, the Social Security System, as well as insurance companies and corporate insurers, among others. The exchange is tentatively scheduled to begin operations in July 2004. II. The Implications of Domestic Bond Market Development for Central Bank PolicyMaking A. Objectives of Monetary Policy The primary objective of BSP's monetary policy is to promote a low and stable inflation conducive to a balanced and sustainable economic growth. The adoption of the inflation targeting framework for monetary policy in January 2002 is aimed at achieving this objective. The inflation targeting approach entails the announcement of an explicit inflation target that the central bank promises to achieve over a given time period. The target inflation rate will be set and announced jointly by the BSP and the government through an inter-agency body, although the responsibility of achieving the target would rest primarily on the BSP. This would reflect an active government participation in achieving the goal of price stability and greater government ownership of the inflation target. To achieve the BSP’s monetary targets, the BSP, can make use of several tools such as open market operations (OMO), reserve requirements, rediscounting facilities and moral suasion. Among the tools available, the OMO is frequently used. Under OMO, the BSP can buy or sell the following for its own account: a. Evidences of indebtedness issued directly by the Government of the Philippines or by its political subdivisions; b. Evidences of indebtedness issued by government instrumentalities and fully guaranteed by the National Government. Aside from OMO, the BSP also makes use of reserve requirements. Banks and NBQBs are required to maintain reserves against their deposit liabilities. Reserves are classified into regular and liquidity reserves. And for liquidity reserves, the banks have the option to maintain them in the form of short-term market yielding instruments bought directly from the BSP. For liquidity reserves, the BSP also makes use of Treasury Bills issued by the National Government. For both instruments/tools, the BSP extensively makes use of government securities. B. Bond Market Development and Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy The BSP’s policy rates, which are set by the Monetary Board, influence the benchmark 91-day Treasury Bill rate, the banks’ lending rates and the whole spectrum of market interest rates. In particular, the short-term market interest rates track closely the movements in BSP’s policy rates. Hence, if the Monetary Board decides to adjust the policy rates, the immediate consequence of such an action would be a parallel change in the short-term rates. However, it must be noted that while short-term rates tend to follow the adjustments in policy rates, they may not change by the same magnitude as the change in policy rates. Meanwhile, the impact of movements of policy rates on long-term interest rates would depend on inflation expectations formed by economic agents and the credibility of the central bank. C. The Benchmark Yield Curve 5 Benchmark securities are important in pricing instruments both at the primary and secondary markets. Government securities, having a lower risk and high liquidity profile can very well serve as benchmark instruments. A benchmark yield curve is usually constructed by market participants from the suite of outstanding treasury securities across a range of maturities. The government treasury securities market plays a significant role in providing a risk-free benchmark yield curve. Any economy that wants to develop corporate bond and derivative markets must have a satisfactory treasury securities market in place. If the domestic securities market functions well under the auspices of finance ministry or central bank, investors will have confidence in the interest rate level available in the markets, which significantly contributes to building their own term structure of rate of returns. Another critical element is that interest rates must be liberalized and determined by market forces. For this reason, the Philippine government undertook to deregulate interest rates in the 1980s. Complementing efforts to liberalize the financial market, reforms were undertaken in the 1990s that led to the emergence of the government bond market as a major venue for mobilizing long-term funds. These include: (a) making government securities eligible as reserves against deposits; (b) broadening the investor base with the granting of more licenses for primary dealers and introduction of small-denominated securities that appeal to retail investors; (c) introducing government securities with longer maturities; and, (d) improving the infrastructure of the government securities market with the automation of the auction process and the introduction of the Registry of Scripless Securities (RoSS). In particular, the issuance of 2-, 5-, 7- 10- and 20year fixed-rate treasury bonds/notes over the past decade was aimed towards providing a benchmark for the pricing of similar term private sector instruments. This has resulted in a longer-yield curve for public sector debt to provide the needed variety and various degrees of liquidity in the market. For the Philippine government securities, the Bankers Association of the Philippines has come up with a Bloomberg page where the market can view fixing rates for benchmark tenors. These fixing rates are derived from various bid quotes submitted by selected contributor banks. Fixing rates are normally based on done transactions. In the absence of done deals, the fixing rates are computed based on the average of the top 60% of bids submitted. Prevailing market rates for securities play an integral part in the review of the country’s monetary policies. Under the inflation targeting framework, the Advisory Committee takes into consideration the movements in the yield curve aside from the volume of done transactions. These provide the Committee with useful information on the investors’ outlook as well preferences and how it will affect the inflation targets set by the government. D. Marketable Securities As provided under Section 92 of Republic Act 7653, the BSP charter, the Bangko Sentral may, subject to such rules and regulations as the Monetary Board may prescribe, issue, place, buy and sell freely negotiable evidences of indebtedness, provided, that issuance of certificates of indebtedness shall be made only in cases of extraordinary movement in price levels. Said evidences of indebtedness may be issued directly against the international reserves of the Bangko Sentral or against the securities which it has acquired under its open market operations, or may be issued without relation to specific types of assets of the BSP. The evidences of indebtedness of the BSP may be acquired before their maturity, either through purchases in the open market or through redemptions at par and by lot if the BSP has reserved the right to make such redemptions. The evidences of indebtedness acquired or redeemed shall not be included among its assets, and shall be immediately retired and cancelled. 6 In 1970, under authority of RA 265, the Monetary Board authorized the issue of Central Bank Certificates of Indebtedness to mop up excess liquidity in urban centers for the purpose of rechanneling the same to the rural areas. CBCIs were issued in 1970-1978 through service agencies at par for a term of three years with tax prepaid 9% interest. In mid-1978 to 1981, CBCIs were redesigned and floated through the auction system, priced at a discount and taxable. Short term Central Bank Bills or CB Bills were issued in 1984 to 1987 with maturities of at least 30 days but not to exceed 360 days, priced at a discount on negotiated basis aimed at curbing the then pervasive inflationary pressures brought about by the 1983 Ninoy Aquino crisis. Special Series CB Bills were also issued in relation to the debt-to-equity conversion transaction requirements. Medium-term Central Bank Notes (5 years) and long-term Central Bank Bonds (10 years) were issued in 1990-1992 as payment for blocked interest payable to commercial banks for enduser, interbank and liquidity swaps. These instruments carried floating interest rates. E. Fiscal and Monetary Policy In the Philippines, the fiscal function of issuing treasury bills and bonds is lodged with the Department of Finance (DOF) through the Bureau of the Treasury. The Auction Committee chaired by the DOF. The authority to borrow rests with the DOF after consultation with the Monetary Board on the monetary implications of the bond issuance. However, the placing, servicing, selling and redeeming of securities remain with the DOF. The independence of the BSP is mandated by law through R.A. 7653. Section 1 of the New Central Bank Act states the Declaration of Policy: “The State shall maintain a central monetary authority that shall function and operate as an independent and accountable body corporate in the discharge of its mandated responsibilities concerning money, banking and credit. In line with this policy, and considering its unique functions and responsibilities, the central monetary authority established under this Act, while being a government-owned corporation, shall enjoy fiscal and administrative autonomy.” Fiscal autonomy entails full flexibility to allocate and use the BSP’s resources while administrative autonomy enables the BSP to discharge duties and conduct operations independent from other branches of government. Coordination of fiscal, monetary and exchange rate policies is undertaken through the Development Budget Coordination Committee (DBCC). The DBCC is chaired by the Secretary of the Department of Budget and Management. DBCC members include the Finance Department, Planning Agency (NEDA), Office of the President, and the BSP. F. Role of the BSP in Supporting Securities Market Development The BSP supports the Government’s efforts to spur the development of capital markets, in particular, the Philippine securities market. Over the last few months, the BSP has embarked on a number of projects designed to enhance the local securities market. It has also actively participated in Congressional hearings for the enactment of measures aimed at improving banks’ non-performing loans. 7 In coordination with the Bankers Association of the Philippines, rules and regulations covering new products had already been issued and circularized. Detailed below are the specific measures recently undertaken by the Bank: The Monetary Board, the policy-making body of the BSP, approved on 1 August 2003, a policy allowing qualified expanded foreign currency deposit units (EFCDUs) of universal and commercial banks to lend their foreign denominated securities holdings to the international market. Securities lending is the temporary exchange of securities usually for other securities or cash of an equivalent value with a contractual obligation to deliver a like quantity of the same securities, at a future date. In allowing securities lending, the BSP hopes to enable EFCDUs to increase the yield on existing portfolios and offset administrative costs. While securities lending is a well-established and organized activity in international financial markets, it is not yet offered in the domestic market. On 1 August 2003, the MB approved the revised Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) for Cash Settled Securities Swap Transactions (CSSTs) among the BSP, the Bureau of the Treasury (BTr), the BAP, the Money Market Association of the Philippines (MART), and the Investment Houses Association of the Philippines (IHAP). CSST is an agreement between financial institutions to simultaneously buy or sell government securities spot, and sell or buy comparable securities at a predetermined future date and price with the same counterparty. The CSST effectively paves the way for the introduction of domestic securities lending in the Philippine market. In more developed financial markets, securities lending type activities are essential to the proper functioning and deepening of secondary market for securities. On February 2004, the BSP relaxed the rules on the sale of non-performing assets (NPAs) under The Special Purpose Vehicle Act of 2002. The relaxation aims to encourage banks and other financial institutions (FIs) to fully avail of the incentives provided for under the Act so that they may once and for all clean their balance sheet of such NPAs. To promote the protection of investors in order to gain their confidence and encourage their participation in the development of the domestic capital market, the BSP issued Circular No. 428 dated 27 April 2004 which sets the rules and regulations which shall govern securities custodianship and securities registry operations of banks and non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) under BSP supervision. A BSP-accredited securities registry must be a third party with no subsidiary/affiliate relationship with the issuer of securities while a BSP-accredited custodian must be a third party with no subsidiary/affiliate relationship with the issuer or seller of securities. These regulations are promulgated to enhance transparency of securities transactions with the end in view of protecting investors. Circular No. 433 dated 13 May 2004 outlines the conditions to be met in order to allow banks to engage in repurchase agreements involving foreign currency denominated government securities. G. Asset-Backed Securities The Securitization Act of 2004 On 19 March 2004, Republic Act No. 9627, otherwise known as the Securitization Act of 2004, was signed into law. The law sets the legal and regulatory framework for the sale of assets (with an expected cash payment stream) like loans, mortgages, receivables and other debt instruments as new securities to raise capital, thus creating a favorable market environment toward the development of the secondary market for these securitized assets. The term assets, however, excludes receivables from future expectation of revenues by government, national or local, arising from royalties, fees or imposts. 8 The law is expected to expand the menu of existing instruments available to investors and provide an avenue for portfolio diversification. It is expected to generate more funds for both the private and government sectors, which can then be used for productive endeavors. Under the law, assets may be sold without recourse to a special purpose entity (SPE) which then issues securities backed up by a pool of similar assets. Several tax privileges will be granted to encourage financial institutions to transfer housing mortgages to SPEs. While the SPEs will still have to pay income taxes as any other corporation, transfers of assets will be exempt from value added and documentary stamp tax. SPEs will also be exempt from the 5% Gross Receipts Tax applicable to a bank/financial intermediary and will be given a 50% discount on all applicable registration and annotation fees. Property transfers, through dacion en pago will similarly be exempt from the 6% tax on capital gains. The Special Purpose Vehicle Act (SPVA) of 2002 The signing of the SPVA on 23 December 2002 is expected to facilitate the removal of banks’ Non-Performing Assets from their balance sheets. On 19 March 2003, the implementing rules and regulations of the SPVA were approved by the Congressional Oversight Committee and this is expected to facilitate the establishment of the needed systems and procedures to ensure efficient transactions. In addition to the main function of investing in, or acquiring the NPAs of financial institutions (FIs), the SPV is also allowed to securitize NPAs acquired from FIs. The incentives and rights to be granted to SPVs include the following: All sales or transfers of NPAs from the FIs to an SPV or transfers by way of dacion in payment by the borrower or by a third party to the FI shall be entitled to the privileges enumerated below for a period of not more than two (2) years from the effectivity of the implementing rules and regulations (IRR). The transfer from an SPV to a third party of NPAs acquired by the SPV or transfers by way of dacion in payment within such two-year period, shall enjoy tax and fee incentives for a period of not more than five (5) years, as shown below: a) b) c) d) e) f) g) documentary stamp tax (DST) capital gains tax creditable withholding income taxes value-added tax (VAT) 50 percent of the mortgage registration and transfer fees 50 percent of the filing fees on foreclosures 50 percent of the land registration fees To further encourage the SPVs to infuse fresh capital and/or provide financial assistance to rehabilitate the borrower’s business, the following additional tax and fee privileges are given to the SPV: a) exemption from income tax on net interest income, DST and mortgage registration fees on new loans in excess of existing loans extended to borrowers with NPLs which have been acquired by SPVs; and b) exemption from DST in case of capital infusion by the SPV to the borrower with NPLs. Prior to the enactment of the above laws, the foundations for publicly issued Mortgage Backed securities had already been laid when President Aquino signed Executive Order No. 90 into law in early 1987. EO 90 established the Unified Home Lending Program (UHLP), a system 9 of subsidized lending for low-cost housing. Loans originated under the UHLP lending guidelines would be purchased by the National Home Mortgage Finance Corporation (NHMFC) for eventual securitization. However, in mid-1996, the government suspended the loan purchase facility of the MHMFC because of poor asset quality of its mortgage assets, and relegated it to collecting its past-due loans. In 1993, the Home Development Mutual Fund (HDMF/Pag-ibig) launched its public mortgage securitization program to further deepen the market for domestic MBSs. In 1998, a commercial bank was expected to launch Home Corp., a special purpose vehicle for securitizing mortgage loans purchased from Pag-ibig but was kept from doing so by poor market conditions. III. Key Challenges in Developing the Domestic Debt Securities Market Impediments to Securitization in the Philippines Limited understanding by most issuer of asset-backed securities (ABS) as a fundraising tool Absence of a common origination documentation standard Inadequacy of customer records Burdensome legal infrastructure and procedures particularly on foreclosures Inadequate external credit rating capacity Limited available issues Limited liquidity mechanism Trading conventions for ABS Shallow secondary market for fixed-income securities Custodianship, clearing and settlement systems income taxation other friction costs (e.g., regulatory fees, etc.) Given these constraints and in line with its mandate of promoting price stability, the BSP has undertaken a number of projects to address some of the above issues. Currently going on are the establishment of the Delivery vs. Payment mode of settlement for government securities, the implementation of the Cash Settled Securities Swap transactions, the implementation of third party securities custodianship/registry and last but not the least, the BSP Custody Project for banks’ proprietary government securities holdings. 10