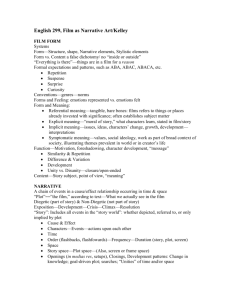

Film Art - Chris McGuire

advertisement