5. automotive sector and components

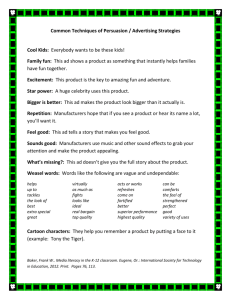

advertisement