- Living Religion

advertisement

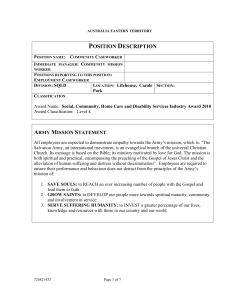

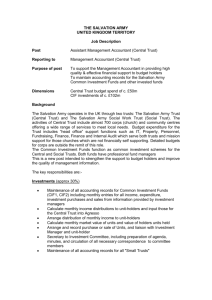

To what extent has the notion of charity been compromised in the social mission of the Salvation Army by the objective of religious conversion? By Stuart Hillman, 2011 The Salvation Army is both a Christian church and a registered charity (The Salvation Army, 2011) that works on a worldwide scale in over one hundred and nine countries (BBC, 2009). It is focused upon spreading the Christian message throughout the world by trying to help those who are deprived or vulnerable in various ways, including running programmes such as drug rehabilitation schemes, providing food, clothes and accommodation for homeless people and attempting to improve the quality of vital buildings such as hospitals and schools (The Salvation Army, 2011). In Australia in one week the Salvation Army provides roughly 3,000 beds for homeless people, 180,000 meals for the hungry, 600 blankets and 20,000 food vouchers, 1,200 people assisted with addictions such as drugs, alcohol or gambling, 4,000 people receive counselling, 800 victims of abuse are provided with shelter, 3,400 elderly people receive care, 40 people are located through family tracing services and roughly 3,000 people find jobs through a job programme that works with the Salvation Army called Employment Plus (The Salvation Army Australia, 2010). Those figures are only in Australia, so if you imagine the work on a global scale, including the other countries in which the Salvation Army works, then the numbers become even more impressive and this shows the Salvation Army carries out many good deeds across the world. However, the intent behind their actions can be questioned as in whether these actions are performed out of Christian love, as one of the key principles of Christianity is the duty to love and care for one another (Woodhead, 2004: 91), or if these actions are done purely with the aim for conversion the Salvation Army’s mission specifically says to try to persuade people to become disciples of God (The Salvation Army, 2011). It could even be argued that it does not really matter at all as the intention behind the charitable deeds does not really undermine the deeds themselves. However, the underlying problem of intention is an important one for the Salvation Army to face because, if charitable deeds are performed for reasons of conversion, then is a charitable deed really charitable as it is arguably therefore not selfless? It must be recognised that if the Salvation Army as a whole were performing charitable deeds with these intentions, then that would contradict one of the basic principles of Christian love. While some may perform such deeds with ideas of conversion , it does not mean that all members of the Salvation Army are similarly motivated because it is clear that first and foremost the Salvation Army values helping people above spreading the Christian message and the idea of conversion. In an attempt to answer the question fully, research has been collected from secondary sources such as books and websites, as well as primary sources that were collected while spending a week with the Salvation Army in Bedworth, in an attempt to gain a better understanding of the inner workings of the Salvation Army. The research method employed in this project mirrors the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski’s method of Participant Observation fairly well, as this was the method of living with the culture or group of people being studied and becoming actively involved in their day to day life, rituals and way of life in order to retrieve the information required (White, 2001). Participant Observation is an ethnographic idea as it is empirical research on a specific culture or religion conducted largely through fieldwork (Hinnells, 2010: 585). Ethnography and participant observation were revolutionary in Malinowski’s time as the idea of living with the subject being studied was practically unheard of and anthropologists of the time would instead rely upon surveys and information collected by missionaries, colonial officers and travellers as they would hardly ever go into the field to retrieve empirical information (White, 2001). Malinowski is particularly famous for his work with the Trobriand Islanders. He spent much time studying the available literature prior to devoting two years of his life to researching them through participant observation (Chryssides & Geaves, 2007: 137). He believed that collecting empirical data and participating in their daily lives was important in order to become familiar with the way subjects think and which would provide the researcher with a personal and ultimately deeper understanding of what they are studying. As the project relies upon ethnographic fieldwork, including interviews, observational study and content analysis, it can draw many parallels with the work of Malinowski, which also means it carries with it the same problems as Malinowski’s. If you follow the method of participant observation overtly, which means openly where everyone involved understands the work you are doing, then many problems can occur. For example, it will be extremely difficult to become completely immersed with the people you’re studying because everyone will know you are researching them. Thus they might not share everything with you as you are not truly part of their culture or they might even tell you exactly what they feel you want to hear as they are aware of your position as a researcher. For instance, in the Salvation Army there is a chance that members will say that they perform actions out of Christian love because they know that is the aim of the project, or they may not answer questions in a particular way to prevent the opposite being proven. At the other end of the spectrum, there is researching a group covertly, which means undercover. This involves lying to the people you are researching and convincing them you are part of their culture or lying about the exact topic of your research to gain the answers you want. The problem with this is that it raises all kind of ethical issues as it is not morally correct to lie to a group of people in the name of research. As well as these issues, there are some more general problems with the participant observation research method, for example you could become too involved and you could almost ‘lose yourself’ in the people you are researching or, if you participate in every activity they perform, then what do you do if they do something you do not necessarily agree with? Do you not perform the action and risk your research and upsetting the people you are studying? Or do you go against your moral code and perform the action in the name of research? For example, if you do not eat meat, yet if you went to a culture that wanted you to kill an animal and eat it, what do you do in that situation? However, by not getting involved as much, you run the risk of not participating enough with the culture, which could be for a variety of reasons including personal beliefs or wanting to maintain a clear divide between researcher and reseached, and then not acquiring quite the same feel or understanding of the people you are studying as you would otherwise. The problem that has occurred here is due to the fact that the researcher and the people being studied would be from two different cultures and therefore the researcher might understand a particular situation or action in a different way, which highlights the difference between the person’s emic perspective and the researcher’s etic perspective. An emic perspective is an insider’s interpretation of their customs or beliefs and an etic perspective is the outsider’s interpretation of the same customs or beliefs (Eou, 2011). For example, the researcher might understand killing animals in a particular way and completely miss what it means to the people. In conjunction with the idea of the pre-existing views of the researcher interfering with participant observation, it is possible that there could be some bias in relation to the person researching with the questions that are asked or the way in which the data is presented afterwards. This is because questions and data can be manipulated to provide any conclusion that is wanted by the researcher, so participant observation largely relies upon the person researching being unbiased and fair. On a more practical level, this method of researching becomes problematic as it can become very expensive and time consuming, as one might have to devote vast amounts of time to the community before members would feel comfortable enough to fully open up and accept the researcher. Not too many people would be willing to sacrifice large amounts of time all at once for their research due to having commitments such as family, other jobs and so forth. Even recording information can become problematic as you could lose notes, break a dictaphone if one is being used or even forget or wrongly record vital details if they are not being written down until later. The final most prominent problem with participant observation, and most research methods in general, is if the particular group being studied is not representative of the society as a whole then any data collected cannot be generalised and therefore on a larger scale it is not valid or useful. Accordingly, if the Salvation Army in Bedworth is not reflective of the entire Salvation Army, and if they deviate from the Salvation Army norms, then any conclusion drawn from the project will not be meaningful beyond the specific community studied. Although there are these problems with participant observation, there are also advantages which suggest that it is actually a very beneficial way to collect information and conduct research. First and foremost, it has the advantage of providing a firsthand view of behaviour in its natural setting, which in turn means that it is a perfect opportunity for detailed research on a smaller scale so it is easier to research the finer details of the inner workings of a group. Especially if you stay for a longer amount of time, it allows you to see the deeper meanings of customs and beliefs that would otherwise be ignored. Any first hand evidence will also benefit a larger scale project because it is easier to figure out what is missing from the project. Then you can also draw upon your previous feelings and experiences to figure out the appropriate questions to ask and how to communicate as part of their society to gain any remaining information needed. Specifically in response to the criticism of participant observation concerning whether one should participate as fully as possible even if one’s moral code tells one it is wrong, the researcher should outline prior to their arrival with the community exactly what they will not do when with the community. Then the researcher can participate to the extent they feel is correct without breaching their own personal moral code or ‘losing themselves ‘in the process by becoming too immersed in the community. In the case of my personal project with the Salvation Army only a week of research was spent there but it was enough to gather the specific information required. Participant observation was an appropriate method for researching the Salvation Army and the question of whether charitable deeds are performed out of Christian love or for the aim of conversion of the people being helped. In conjunction with Malinowski’s work, that of American anthropologist Richard Geertz and his idea of ‘Thick Description’ is also useful. ‘Thick Description’ is a description of human behaviour that does not just describe the behaviour but also the context in which it is located and the meaning behind it, that allows someone who is not part of that community to make sense of it (Alles, 2010: 44). For example, members of the Salvation Army should go to church on Sunday and thick description would state this but would add that the reason for this is because it is a way of becoming even closer to God (Bechtle, 1997). So it has been clearly shown that an appropropriate method for studying the Salvation Army was Malinowski’s method of Participant Observation by becoming involved with the day to day life of the Salvation Army for a week, and by conducting interviews and observations. In preparation, however, I had to read about the Salvation Army to understand the origins and motives of the movement. Barnes (1978: 33) defines the Salvation Army as ‘a force of converted men and women, joined together after the fashion of an army, who intend to make all men yield, or, at least, listen to the claims when God has to their love and service’, which shows that God is the main driving force behind the Salvation Army and any actions members may perform including charitable deeds. Thus it can be seen that the charitable deeds performed by the Salvation Army would be an expression of God’s love for people and spreading God’s love, or at least that is how it appeared at this point. This point is supported by the fact that every Salvation Army officer promises that he or she will take care of the poor, feed the hungry, clothe the naked, love the unlovable and befriend the friendless (The Henley Centre, 2004: 93). So the people of the Salvation Army act out of a deep love for God and people, to help those less fortunate rather than out of an ulterior motive of religious conversion. The Salvation Army is partly run through government funding for several of its programmes that could not be run purely on charitable reserves and donations alone. However it does heavily rely upon donations from the public and the time and effort provided by volunteers as the Salvation Army has the aim that all their churches and centres in the United Kingdom become vital parts of their communities. This means that they function not only as places of Christian worship but also places where people can look for support, engage with other people and access services like shelter for the homeless (The Henley Centre, 2004: 93-94). Across the world celebrities have supported the charitable deeds of the Salvation Army, for example, Jackie Chan who visited the Salvation Army unit in Yau Ma Tei in Hong Kong and donated four hundred and fifty coats to victims of a snowstorm in 2008 (The Official Website of Jackie Chan, 2008). This is a typical example of the disaster relief work undertaken by the Salvation Army, because in cases of emergencies members are trained to provide help to the emergency services (The Salvation Army, 2010). The origin of the Salvation Army provides support for the argument that members of the Salvation Army perform charitable deeds out of a love for other people and the word of God. The founder, William Booth, travelled across England until around 1861 when he devoted his time to evangelistic work. In 1865 he established the Salvation Army in the belief that he was guided by God to serve in the East End of London where he devoted his life to helping people hear, understand and know God and save them from a life he saw as miserable and degraded (Barnes, 1978: 33). Booth stated: The denizens in Darkest England, for whom I appeal, are (1) those who, having no capital or income of their own, would in a month be dead from sheer starvation were they exclusively dependent upon the money earned by their own work; and (2) those who by their utmost exertions are unable to attain the regulation allowance of food which the law prescribes as indispensable even for the worst criminals in our gaols. (Booth, 1970: 18) The quotation from Booth shows that he felt that it was necessary to help those less fortunate, he then spent the rest of his life devoted to the Salvation Army, spreading the word of God and helping people who he felt needed it. Apart from being motivated by a love of people, it becomes apparent that he may also have been motivated to help those less fortunate due to the fact that his father died when he was only fourteen, leaving him as one of the main income providers for his family while on a pawnbroker’s apprentice’s salary. It is extremely like that he also helped people and performed charitable deeds because he was trying to prevent people from experiencing what he experienced when he was younger (The Salvation Army Australia, 2011). A similar motivation can be seen in the life story of his wife, Catherine Booth, who was frequently ill during her teenage years. This inspired her to help people. She worked mostly with alcoholics and young people in an attempt to prevent them from suffering for years the way she had. She was extremely important to the work of her husband, William Booth, as she was the one who convinced him that women were the equals of men, which led to William Booth emphasising gender equality within the Salvation Army (The Salvation Army Australia, 2011). However, it must be remembered that the Salvation Army was formed in the mid-nineteenth century and, while the world still faces similar problems such as alcoholism, the Salvation Army does need to reassess constantly the way it works to continue to help people. While there are similar problems in the world today, they all exist on a different scale so the Salvation Army needs to revolutionise itself especially when it comes to things such as a need for volunteers (The Henley Centre, 2004: 99). So from analysing the Salvation Army through its origins and history it can be seen that most charitable acts were performed out of love, in the attempt to stop people experiencing similar difficulties to those which William and Catherine Booth has faced. There are several responses to the question to what extent has the notion of charity been compromised by religious conversion, and to explore this question correctly the research conducted while spending time with the Salvation Army of Bedworth was used. The words of William Booth and the research from books and websites only show part of what the Salvation Army does, and the empirical data from the research allowed the question to be explored further. One of the main possibilities is that charity has been completely compromised by religious conversion and all charitable deeds performed by the Salvation Army are inspired by the attempt to spread the word of God and convert people. There are several examples to support this argument from the research I collected at the Salvation Army, but they are not conclusive. For example, every Friday night the Salvation Army in Bedworth works with other churches in the area to walk the streets to talk to young people. Some could argue that as young people are impressionable, this is simply to try to convert them rather than talk to them about any problems they have and make them feel better. However the example is not as clear as this in my experience as members did not actually discuss religion with the youths and it was not until afterwards when the people returned to the church that they offered a small prayer to help those they had met. Another dimension is added to this argument once you consider the fact that these are religious people so praying for people to be helped or trying to find other people to join their religion is not a negative thing, because they would consider allowing someone to experience God is just as helpful and charitable as feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless or clothing the naked. So is it justifiable to say that the Salvation Army works only to convert people? Accordingly, it is extremely difficult to argue that the work of the Salvation Army is purely inspired by the hope of conversion, because the way in which members work never forces religion upon people. This leads us to another possibility which is that they act completely out of love for people and helping people is the entire intention behind the act. This position can be supported simply by acknowledging that the Salvation Army runs through the help of volunteers who can be of any faith or none. Therefore conversion cannot be the only intention behind the work of the Salvation Army, as people from many different backgrounds volunteer there or work alongside members. For example, in Bedworth, there is a Sikh man who works as a drug counsellor to help people who have ‘substance issues’, working with the Salvation Army so he can provide his services for more people and raise awareness of the work he does. He felt that the Salvation Army had never once infringed upon his personal beliefs or tried to convert him and that members focused completely on helping as many people as possible. In conjunction with this, a volunteer who was not part of the Christian faith, said that it was like a second home to him as the Salvation Army is so welcoming and inclusive He had never felt any pressure to adopt any sort of beliefs or faith and the Salvation Army in Bedworth was an extremely important part of their community. The impact upon the community was a recurring theme for the people I spoke to for this project, all agreeing that the Salvation Army in Bedworth has become more about making a difference with people, including just having somewhere for people to gather and interact because, especially for groups of people such as the elderly, it is extremely beneficial for them to have somewhere to go like the Salvation Army. A woman who regularly attended the Salvation Army said that it is vital because she can always find help there as the organisation does a lot of social work in their local area including raising money for people, and it also provides her with a place she can go and see her friends. The Salvation Army does in fact become like a second home to many of the people who regularly attend regardless of their faith. Another aspect that needs to be considered is that the volunteers also benefit from the volunteering they perform, because some of the volunteers use it for experience for a future job, but other volunteers may be out of work or retired and volunteering at the Salvation Army provides them with something to do which they enjoy as well as being able to help people. So volunteering at the Salvation Army benefits people in all sorts of ways, from those being helped to affecting the lives of those volunteering, but the idea of conversion rarely seems to occur to the non-Christian volunteers who focus on work they do for the community in their area. Therefore we can conclude from this is that Salvation Army members act out of love with the hope that those they meet will find faith, rather than actively seeking to convert people. This is not necessarily acting with an ulterior motive rather than altruistically and it is still doing charitable deeds out of love as there is no active converting agenda. Here a new possibility emerges: does it even matter if they are doing charitable deeds with an aim of conversion? Does an aim of religious conversion really undermine the charitable deeds themselves? What if someone is helped and then embraces the faith of the Salvation Army and that benefits them further? How can that be a bad thing? The Salvation Army in Bedworth has a programme run with a prison nearby where members can visit the prisoners, talk to them and set them up for a better life when they leave prison. Some of the prisoners are non-religious or nonChristian, but they really appreciate the company provided. For example, one woman I met had gone twice in her life and she said despite only going twice the prisoners appreciated her visit so much they remembered exactly who she was. The point made here is that, even if the aim of her visiting the prison was to convert, that does not mean the time she spent with the prisoners was any less important or vital to them and that does not make the deed any less charitable. A similar example is the Salvation Army’s work with homeless people. During the research period I went to a nearby Salvation Army centre where there is a homeless programme on a Wednesday evening every week. While there I found out the full extent of how the organisation helps homeless people, by providing them with meals, shelter, clothes, socks and sleeping bags and offering programmes to help them in the long term. If someone was performing all of these charitable deeds with the intent of converting one of the people they helped to the Christian faith, how does that make the charitable deed any less amazing? It could be argued that it is not strictly charitable because they are attempting to gain members, however it is still charitable because the amount of good these actions do outweighs any negative consequences arising from motives of conversion. The role of volunteers, who are not members of the Salvation Army, would question the importance of the motive of conversion, as the Salvation Army do so much good for so many different people regardless of the religion of either volunteers or clients. From the research conducted on the Salvation Army through Participant Observation and reading of secondary sources it is clear that one of the main aims of the Salvation Army was to convert people to the Christian faith, but this aim has become secondary to helping people in need and Salvation Army members whom I met did not rate conversion as a more important aim of the work they do than the aim of helping people. So it can seen there is essentially no overt attempt to convert people in the Salvation Army, at least not in Bedworth, so the notion of charity has not been compromised in the context of religious conversion. This is because there do not seem to be any major signs of attempted religious conversion in order to qualify for charitable help. In any case, a motive of conversion would not undermine the incredible good that comes from the Salvation Army helping elderly people, homeless people, those with addictions to drugs, alcohol and gambling and other forms of practical support such as helping fix someone’s boiler if it breaks. It could even be argued that the Salvation Army has placed little emphasis on the religious rather than the ethical aspects of their activities because so many of the volunteers and people who donate are non-religious or of a different faith. Almost the opposite could be true, and instead the Salvation Army could be seen as trying to be all inclusive and welcoming to everyone, therefore minimising their religious side so no one feels as if they cannot be associated with the Salvation Army. So it cannot be argued that the Salvation Army is compromising its notion of charitable deeds, because these are clearly performed out of a love for people and an attempt to change the world for the better. Bibliography Alles, G. (2010) ‘The Study of Religions: The Last Fifty Years’. In: Hinnells, J.R. ed. The Routledge Companion to The Study of Religion. 2nd Ed. Abingdon & New York: Routledge, pp. 39-55. Barnes, C. (1978) God’s Army: Over a hundred years of war against poverty, sickness and evil: the illustrated story of the Salvation Army. Berkhamsted: Lion Publishing. BBC (2009) Salvation Army [Online] Available From: http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/subdivisions/salvationarmy_1.sht ml [Accessed: 15.01.2011]. Bechtle, J. (1997) Why should Christians go to Church? Why is it important? [Online] Available From: http://www.christiananswers.net/q-acb/acb-t009.html [Accessed: 15.01.2011]. Booth, W. (1970) In Darkest England and The Way Out. 6th Ed. London: Lewis Reprints Limited. Chryssides, G. D. & Geaves, R. (2007) The Study of Religion: An Introduction to Key Ideas and Methods. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group. Eou (2011) Emic and Etic [Online] Available From: http://www2.eou.edu/~kdahl/emicdef.html [Accessed: 15.01.2011]. The Henley Centre (2004) The Responsibility Gap. London: The Salvation Army. Hinnells, J. (2010) ‘Glossary’. In: Hinnells, J.R. ed. The Routledge Companion to The Study of Religion. 2nd Ed. Abingdon & New York: Routledge, pp. 581-594. Jackie Chan Official Website (2008) Jackie donates 450 coats to China Snow Relief Effort [Online]. Available From: http://jackiechan.com/news/206058--JackieDonates-450-Coats-to-China-Snow-Relief-Effort [Accessed: 15.01.2011]. The Salvation Army (2011) What Does The Salvation Army Do? [Online] Available From: http://www1.salvationarmy.org.uk/uki/www_uki.nsf/0/5D35EC2B04BC515880256F 1900494FA9?Opendocument [Accessed: 15.01.2011]. The Salvation Army Australia (2011) Founders William and Catherine Booth [Online] Available From: http://salvos.org.au/about-us/our-history/william-andcatherine-booth.php [Accessed: 23.01.2011]. The Salvation Army Australia South Territory (2010) FAQ: Helping People – How many people does the Salvation Army assist? [Online] Available From: http://www.salvationarmy.org.au/students/helping.asp [Accessed: 23.01.2011]. White, E. (2001) Bronislaw Malinowski: Identifying the Kula Ring of the Trobriand Islanders: The Role of Ethnographic Field Observation in Pattern Recognition [Online] Available From: http://www.csiss.org/classics/content/98 [Accessed: 15.01.2011]. Woodhead, L. (2004) Christianity: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.