Hotel Rwanda Blessed are the Peacemakers they shall be called

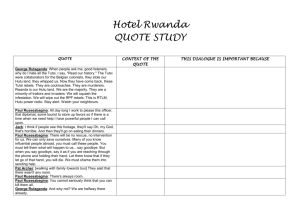

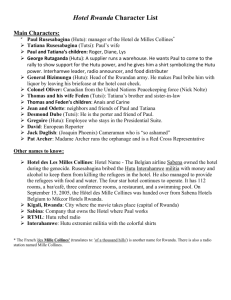

advertisement

Hotel Rwanda Blessed are the Peacemakers they shall be called the Children of God Hatred destroys not only the other but also oneself. In maintaining hate we sacrifice ourselves to the lie that the enemy deserves to die. That war breeding more war, ” is only a cowardly escape from the problems of peace” (Thomas Mann). The only way to overcome an enemy is to make the enemy a friend. The problem of peace is how to make an enemy a friend. To make peace is to move beyond apathy or tolerance. To make peace is to create community. Community is created when we live in such a way that the energies of all are allowed positive expression. It is a question of imagination. Because we live in imagined worlds, what we imagine as real defines how we relate with others. When we indulge ourselves to imagine the world, instead of allowing ourselves to live as God imagines us, we follow the path of fantasy. And, as Yeats observed of those fighting against each other in the civil war in Ireland: Their hearts are fed by fantasies Their hearts have grown brutal from the fare. Before we can create community we need to ask what fantasies shape our lives and, further, what are the forces in our lives which come together to maintain those fantasies. If we see only out of our hurts — rather than the call to creativity which gives us our vision — we project onto those we hate those forces that have hurt us and which we deny being in our own lives. But we know they are there because they trap us and we feel hate One becomes a peacemaker only as one makes peace with oneself, only as one acknowledges the hurt in one’s life, through a healing of memories and sensibilities within that vision which gives our life meaning. That vision emerges when we accept that we are all held in the compassionate mercy of God, and that noone is outside of that mercy. This meaning becomes real in our lives not in terms of satisfaction but through the modes of consolation. In consolation one is redefined not according to fantasy but through an immediate openness to God. That state “without any previous cause” moves us beyond our boundaries to a new awareness of reality in which what we could not consider possible is possible. In this openness the enemy can become the friend. That openness does not manipulate the other into becoming a friend. There is always the other’s freedom of choice. Even self-sacrificing love –radical openness - does not make the other free. But it is the most we can do. We can love our enemy without indulging our enemy’s destructiveness, and hope for the best. That is our calling as human beings. We love each other, or we die. Christ, the peacemaker, comes to show us how to reconcile ourselves to God, to each other, to ourselves, and to all the forces of creation. Reconciling the estranged is the mission of the peacemaker, the Son of God. He does it by showing we all have a common source, the Father, and that we are all one in that same Father. We, his companions, also inherit that same mission from God according to today’s beatitude. Community can be built only if there is shared a common vision when everyone maintains a common good. That common good is manifested differently according to different gifts but underlying difference is the same spirit and a common vocation. The dynamics of integration that is necessary to be a person of peace is also necessary to be a community. Prayer, dialogue, openness, intimacy, and celebration, create life. The path of the peacemaker leads to the broken and hard places of one’s own life, one’s own community, and one’s own world. It takes up the Standard and Cross of Christ, our brother. We stand in those places, simply and humbly, as open doors –in our poverty of spirit — and as open doors we allow the mercy of God to enter the world, and we allow the pain of the world to pass through us to be held by that transforming love of God. Questions for Reflection: 1. Who is our community–the ones we share our lives with? Why do we hold that? How did we come to those relationships? 2. How do we find our community ? Does it support our integrity? Are we inspired by the community, the society, the culture we live in? 3. What ideals of community life do we hold that alienate us from the people we live with? — Do we know the estranged parts of our life? 4. Do we know the integrated parts of our life? Do we live out of alienation or integration with ourselves, with our community, How do we realize, individually and collectively, our call to be peacemakers where we find ourselves now? 5. Who is not our community? Why do we say that ? How do we treat those others? 6. What boundaries do we impose upon our imagining ourselves? Are those boundaries open or closed? 7. How do we experience ourselves, and others, as mystery? Whom are we intimate with? 8. How are we intimate with ourselves — in terms of self-awareness, self-knowledge, being comfortable with ourselves, loving ourselves into transcendence ? 9. How are we intimate with others? How are we intimate with God, so that God can be fully present, through us, in the world? 10. What are the difficulties we have with intimacy ? What stops us from trusting? What concrete elements stop us from risking — that movement beyond trust into the darkness ? What forms of fear, of established positions, of power, of disillusionment, possess us? Scripture Passages for Praver: John 17: 6- 26 1 John 1: 5 - 2: 17 1 Corinthians 12: 1 -14 1 Genesis 22: 1- 14 Genesis 32: 24 - 31 Song of Songs 3: 1 -5; 8: 6-7 Revelation 21: 1 — 8 John 14: 15 - 15: 17 Gal. 5:13 - 6: 2 Eph. 2: 8 - 22, 4: 1 - 16 Rom. 5:1-11 Dan. 10:15 -19 Isaiah 11:1 -11 The Film: Hotel Rwanda, directed by Terry George, written by Keir Pearson and Terry George Hotel Rwanda aims to tell the story, through the experience of the manager of a luxury hotel in the Rwandan capital of Kigali, of the horrific genocide that took the lives of as many as 1 million people, mostly Tutsi, who were slaughtered by Hutu militias in the central African country within a three-month period in 1994. Don Cheadle plays the role of Paul Rusesabagina, the Hutu manager of the Belgian-owned Hotel des Milles Collines. Rusesabagina leads a relatively privileged life, but he is married to a Tutsi, and is both personally threatened and politically horrified by the nationalist frenzy, in which Hutu radio announcers call for the crushing of the “Tutsi cockroaches.” He later escaped the slaughter with his family, and lives in Belgium today. Rusesabagina is the central character in this story, and he assisted director and screenwriter Terry George with the screenplay. The job of hotel manager brings Rusesabagina into contact with the local ruling elite as well as European officials and businessmen. He uses his first-hand knowledge and connections to save his family, and also to shelter about 1,200 refugees, mostly Tutsis, along with Hutus who oppose the ethnic killing. These people have been lucky enough to find refuge in the hotel, where they await their fate under conditions of severe overcrowding, limited supplies and above all overwhelming fear, while the genocide continues just outside. The film traces the development of the genocide over a number of weeks. The signal for the attacks is the radio’s call to “cut down the tall trees,” announced after the plane carrying Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana is shot down as he is returning from Tanzania, where he has signed a peace agreement with the rebel Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). The parties responsible for downing the President’s plane have never been determined, and one theory is that Hutu ethnic extremists may have taken the opportunity to remove him while also providing a convenient excuse for launching the mass killing. Over the next days and weeks there are, not unexpectedly, a number of very narrow escapes, both for Rusesabagina as well as his “guests.” In the end, a combination of quick thinking and tactical maneuvers by the hotel manager, along with sheer good luck, enable him to prevail. Rusesabagina buys time by bribing a powerful Hutu general with liquor, Cuban cigars and cash. At the most desperate moment, as the general is about to unleash the Hutu militia in the hotel, the manager gambles that this military gangster can be intimidated by the threat of possible war crimes trials. Rusesabagina warns him that he will not be around to testify for the general if he is killed. Hotel Rwanda also deals with the legacy of imperialism and colonialism, and the film alludes to imperialism’s role. At one point, for instance, UN peacekeeper Col. Oliver (Nick Nolte) bitterly explains to Rusesabagina that the genocide will not be stopped because the Western powers are not interested in Africa. The supposed indifference is ascribed to racism. In fact, the rival imperialist powers were not simply “indifferent” to the Rwandan tragedy. They were and are indifferent when it comes to the misery and suffering of the African masses, but they have also intervened for their own geopolitical advantage. Revelations after the 1994 genocide showed how the rival powers, principally France and the United States, jockeyed for advantage in the midst of the carnage, backing the Hutu government or the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front, and thus contributing to the genocide. Above all, the horrific events of 1994 cannot be understood apart from the history of Rwanda and of sub-Saharan Africa as a whole. To the extent that it discusses responsibility for the Rwandan genocide, moreover, Hotel Rwanda suggests that “we are all guilty.” A Western television journalist, played by Joaquin Phoenix, tells Rusesabagina that television footage of the slaughter won’t lead to any aid. “If people see this footage, they’ll say, ‘Oh my God, that’s terrible,’ and they’ll go on eating their dinners,” he declares. Questions about the film: 1. A film basically gives one perspective. Other perspectives are alluded to or ignored. This film treats of one man’s efforts to maintain his integrity in a context that is beyond his control or sanity. We see his redeemed history? What is the unredeemed history in the film? 2. How did making the film change Don Cheadle? 3. Can we distinguish between peace-lovers; peace-keepers, and peace-makers? Where do we find ourselves as members of a common humanity? of a common culture? of a common church? as individuals? 4. A huge temptation in watching a film like this is to feel guilty, or to deflect our responsiblity for each other. This STOPS the real work of making peace. Note peace-making is a stage on a journey, and cannot happen before the previous stages are established. If we feel guilty or deflect, it means that there is more work to be done at one of the previous stages of the beatitudes. [Note, for example, that the hotel manager has married someone from the “opposing” side. He has opened himself to “the other” in love, and this allows him to move beyond ethnic divisions. He lives the beatitude of meekness] If we feel either guilt or apathy, what do you think is the necessary work that needs to be done? Questions about the film and our entry into this beatitude. 1. What do we do to bring about the Kingdom of God in our daily lives? 2. What moment in the film touched us the most? What does that say about where we are in our spiritual journey? 3. How do you see the film as a manifestation of the gospel reality of the passion of Christ? 4. The film portrays a struggle between good and evil in a particular historical context. How does it reveal to us our own divided hearts, and the ways in which we are invited to do good and the ways in which we succumb to evil? 5. In our conversations with God at the end of our prayer, what manifested itself to us?