File

advertisement

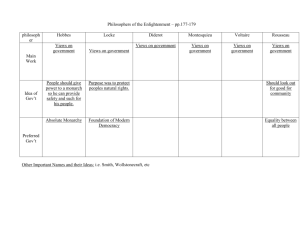

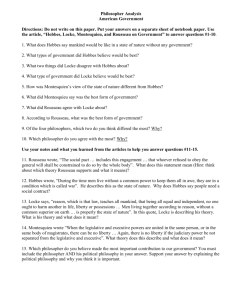

Enlightenment Trading Cards Project You will create a set of trading cards (like a baseball card) describing an Enlightenment figure from the 1600s or 1700s. You will be given a blank index cards to use for this project. Assignment is due in class 2/12 and is worth 100 pts. People to Research: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) 9) Thomas Hobbes John Locke Voltaire Baron de Montesquieu Jean-Jacques Rousseau Cesare Beccaria Denis Diderot Mary Wollstonecraft Adam Smith Information you need from the notes/internet: Back: (be sure to write out or abbreviate all numbers & categories) 1. Write their full name (real name if applicable) 2. Date of birth 3. Date of death 4. Place of birth (city & country) 5. Contributions to enlightenment 6. Major writing/work 7. What idea do they most believe in 8. Ideas about the government 9. Interesting fact or quotes 10. Source (from internet – write full URL) Front: 1. Photo of the person no larger than an index card (4x6) 2. Photo of flag of their country during the time they lived. 3. Country they are from or most associated with. Use the Internet, your notes and the textbook to research this project. You must cite any source from the Internet, like occupation, quotes, etc (list the full web site address). You do not need to cite your notes or textbook. Example of how your card will look: Thomas Hobbes Name Picture Front Flag England Country 1. Thomas Hobbes 2. DOB: 3. DOD: 4. POB: 5. Contributions: 6. Major work: 7. Major belief: 8. Ideas about Gov: 9. Fact/Quote: 10. Source: Back Thomas Hobbes - Biography Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) Thomas Hobbes was born at Westport, adjoining Malmesbury in Wiltshire, on April 5, 1588. His father was the vicar of a parish. His uncle, who was a tradesman and alderman of Malmesbury, provided for Hobbes' education. When he was 14 years old he went to Magdalen Hall in Oxford to study, already an excellent student of Latin and Greek. He left Oxford in 1608, and became the private tutor for the eldest son of Lord Cavendish of Hardwick (later known as the Earl of Devonshire). He traveled with his pupil in 1610 to France, Italy, and Germany. He then went to London to continue his studies, where he met other leading scholars like Francis Bacon, Herbert of Cherbury, and Ben Johnson. Hobbes maintained his connection to the Cavendish family, however, in 1628 the Cavendish son died, and Hobbes had to find another pupil. In 1629 he left for the continent again for a two year journey with his new student. When he returned in 1631 he began to tutor the younger Cavendish son. It was around this time that Hobbes' philosophy began to take form. His manuscript Short Tract on First Principles was most likely written in 1630. In this piece he uses the geometrical form, inspired by Euclid, to shape his argument. From 1634 to 1637 Hobbes returned to the continent with the young Earl of Devonshire. In Paris he spent time with Mersenne and the scientific community that included Descartes and Gassendi. In Florence, he conversed with Galileo. When he returned to England he wrote Elements of law Natural and Politic, which outlined his new theory. The first thirteen chapters of this work was published in 1650 under the title Human Nature, and the rest of the work as a separate volume entitled De Corpore Politico. In 1640 he went to France to escape the civil war brewing in England. He would stay in France for the next eleven years, taking an appointment to teach mathematics to Charles, Prince of Wales, who came to Paris in 1646. At this time Hobbes friend Mersenne was encouraging scholars to respond to Descates' forthcoming treatise Meditationes de prima philosophia. In 1641 Hobbes sent his critique to Descartes in Holland, and they were published in Objectiones with the publication of the treatise. The two men continued their discourse, exchanging letters on the Dioptrique, which had been published in 1637. Hobbes disagreed with Descartes' theory that the mind, independent from material reality, was the primal certainty. Hobbes instead used motion as the basis for his philosophy of nature, mind and society. His correspondence with Descartes led to a paper on his views on physics and a Tractatus Opticus to works published by Mersenne. By 1640 Hobbes had plans for his future philosophical work, expecting it to take shape in the form of three treatises. He planned to begin with matter, or body, then look at human nature, and then society. However, inspired by the political unrest in his home country, he began instead with the third treatise on society. De Cive was published in Paris in 1642. When the Commonwealth had reestablished a stable government in England, Hobbes published the same text in English under the title Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society. The book was highly controversial, and criticized by both sides of the English civil war. He supported the king over parliament, but also denied the king his divine right. Oxford University dismissed faculty under the premise of being "Hobbits". Hobbes also ventured controversial views on God and religion, and the Roman Catholic Church put his books on the Index. In England ther In 1651 Hobbes returned to England, fearing that France was no longer a safe haven for the exiled English court. This same year saw the publication of Leviathan, Hobbes' most influential work. In the introduction to the book Hobbes describes the state as an organism, showing how each part of the state functions similarly to parts of a human body. As the state is created by human beings, he first sets out to describe human nature. He advises that we may look into ourselves to see a picture of general humanity. He believes that all acts are ultimately self-serving, even when they seem benevolent, and that in a state of nature, prior to any formation of government, humans would behave completely selfishly. He remarks that all humans are essentially mentally and physically equal, and because of this, we are naturally prone to fight each other. He cites three natural reasons that humans fight: competition over material good, general distrust, and the glory of powerful positions. Hobbes comes to the conclusion that humanity's natural condition is a state of perpetual war, constant fear, and lack of morality. In the Leviathan, Hobbes writes that morality consists of Laws of Nature. These Laws, arrived at through social contract, are found out by reason and are aimed to preserve human life. Hobbes comes to his laws of nature deductively, still using a model of reasoning derived from geometry. From a set of five general principles, he derives 15 laws. The five general principles are (1) that human beings pursue only their own self-interest, (2) that all people are equal (3) the three natural causes of quarrel, (4) the natural condition of perpetual war, and (5) the motivation for peace. The first three Laws of Nature he derives from these principles describe the basic foundation for putting an end to the state of nature. The other twelve laws develop the first three further, and are more precise about what kind of contracts are necessary to establish and preserve peace. Hobbes saw the responsibility of governments to be the protection of people from their own selfishness, and he thought the best government would have the power of a sea monster, or leviathan. He saw the king as a necessary figure of leadership and authority. He felt that democracy would never work because people are only motivated by self-interest. He saw humanity as being motivated by a constant desire for power, and to give power to the individual would result in a war of every one against the other that would make life "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." After returning to England in 1651, Hobbes had spent a couple of years in London, before retreating to the home of his former pupil the Earl of Devonshire. In 1654 Hobbes was surprised by an unauthorized publication of a tract entitled Of Liberty and Necessity, which he had written in response to an attack by the bishop Bramhall on Leviathan. Bramhall was enraged by Hobbes response, and Hobbes was prompted to write a further and more elaborate defense in The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity, and Chance, which was published in 1656. In 1655 Hobbes published De Corpore, the first part of his philosophical system. This work looks at the logical, mathematical and physical principles that create the foundation of his philosophy. The second part of his system, De Homine, was published in 1656. In 1667 Leviathan was mentioned in a bill passed in the Commons against blasphemous literature. Although the bill did not pass both houses, Hobbes was scared into studying the law of heresy, and wrote a short treatise arguing that there was no court that might judge him. He was forbidden to publish on the topic of religion. Many of his works were kept from publication, however a Latin translation of Leviathan was published in Amsterdam in 1668. Around this time he also wrote Dialogue between a Philosopher and a Student of the Common Laws of England. Among the titles that remained unpublished during his lifetime are the tract on Heresy, and Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England. He continued to write, and he wrote his autobiography, in Latin verse, when he was eighty-four years old. In his final years he completed Latin translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and in 1675 he left London for the last time to live with the Cavendish family in Derbyshire. Hobbes died at Hardwick on December 4, 1679. John Locke - Biography John Locke (1632-1704) John Locke was born on August 29, 1632, in Warington, a village in Somerset, England. In 1646 he went to Westminster school, and in 1652 to Christ Church in Oxford. In 1659 he was elected to a senior studentship, and tutored at the college for a number of years. Still, contrary to the curriculum, he complained that he would rather be studying Descartes than Aristotle. In 1666 he declined an offer of preferment, although he thought at one time of taking up clerical work. In 1668 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1674 he finally graduated as a bachelor of medicine. In 1675 he was appointed to a medical studentship at the college. He owned a home in Oxford until 1684, until his studentship was taken from him by royal mandate. Locke's mentor was Robert Boyle, the leader of the Oxford scientific group. Boyle's mechanical philosophy saw the world as reducible to matter in motion. Locke learned about atomism and took the terms "primary and secondary qualities" from Boyle. Both Boyle and Locke, along with Newton, were members of the English Royal Society. Locke became friends with Newton in 1688 after he had studied Newton's Principia Mathematica Philosophiae Naturalis. It was Locke's work with the Oxford scientists that gave him a critical perspective when reading Descartes. Locke admired Descartes as an alternative to the Aristotelianism dominant at Oxford. Descartes' "way of ideas" was a major influence on Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Locke studied medicine with Sydenham, one of the most notable English physicians of the 17th century. His skills in medicine led to an accidental encounter with Lord Ashley (later to become the Earl of Shaftesbury) in1666, which would mark a profound change in his career. Locke became a member of Shaftesbury's household and assisted him in business, political and domestic matters. Locke remained at Shaftesbury's side when the Earl was made Lord Chancellor in 1672, making presentations to benefices, and eventually becoming his secretary to the board of trade until 1675, when Shaftesbury lost his title. Locke's ideas on freedom of religion and the rights of citizens were considered a challenge to the King's authority by the English government and in 1682 Locke went into exile in Holland. It was here that he completed An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, and published Epistola de Tolerantia in Latin. The English government tried to have Locke, along with a group of English revolutionaries with whom he was associated, extradited to England. Locke's position at Oxford was taken from him in 1684. In 1685, while Locke was still in Holland, Charles II died and was succeeded by James II who was eventually overthrown by rebels (after more than one attempt). William of Orange was invited to bring a Dutch force to England, while James II went into exile in France. Known as the Glorious Revolution of 1688, this event marks the change in the dominant power in English government from King to Parliament. In 1688 Locke took the opportunity to return to England on the same ship that carried Princess Mary to join her husband William. Locke had written Two Treatises of Civil Government in the early 1680s while Whig revolutionary plots against Charles II were still in the works, and in 1690 he was finally able to publish them. This work is a theory of natural law and rights in which he makes a distinction between legitimate and illegitimate civil governments and argues for the legitimacy of revolution against tyrannical governments. He saw that the reason government is established is to protect the life, liberty and property of a people, and if these goals are not respected, then rebellion is entirely permissible by the population who originally consented to the government's power. The first treatise is an attack on Sir Robert Filmer and his text Patriarcha (1680), which he wrote in defense of divine monarchy. Locke uses this critique to launch his criticism of the work of Thomas Hobbes. In the Second Treatis Locke states his theory of natural law and natural right, revealing a rational purpose to government. Locke felt that the public welfare made government necessary and was the test of good government, and he always defended the government as an institution. In 1690 Locke was also able to publish An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which he had been working on since 1671. In this book he establishes the principles of modern Empiricism, and attacks the rationalist concept of innate ideas. Drawing on earlier writings by Chillingworth in which human understanding is said to be limited, Locke sets out to determine these limits. He writes that we can be certain that God exists, and be as certain of mortality as we are of mathematics, because we create moral and political ideas. He states that we cannot, however, know the underlying realities of natural substances, as we can only know their appearance. He imagined that the human mind begins as a "tabula rasa," and that we learn by our experience. The new government of England offered Locke the post of ambassador to Berlin or Vienna in recognition of his part in the revolution, however Locke declined the honorable position. In 1689 he became commissioner of appeals, and from 1696 to 1700 acted as commissioner of trade and plantations. In 1691 Locke responded to financial difficulties in the government by publishing Some Considerations of the Consequences of Lowering of Interest, and Raising the Value of Money, and in 1695 Further Considerations on the topic of money. In 1693 he published Some Thoughts Concerning Education, and in 1695 The Reasonableness of Christianity. He was later inspired to write two Vindications of this last work in response to some criticism. Locke invested a great deal of energy in theology in his later years, and among his work published post mortem are commentaries on the Pauline epistles, a Discourse on Miracles, a fragment of the Fourth Letter for Toleration, and An Examination of Father Malebranche's Opinion of Seeing all things in God, Remarks on Some of Mr. Norris's Books. After his death another chapter of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding was published under the title The Conduct of the Understanding. In his final years he lived in the country at Oates in Essex at the home of Sir Francis and Lady Masham (Damaris Cudworth). Locke had met Cudworth in 1682, a philosopher and daughter of the Cambridge Platonist Ralph Cudworth. They had an intellectual and amorous relationship, which was cut short by Locke's exile in Holland. Cudworth had married Sir Francis Masham in Locke's absence, yet she and Locke remained close friends. Before his death, Locke saw four more editions of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding and entertained controversy and critiques regarding the work, engaging in a series of letters with Edward Stillingfleet, Bishop of Worcester, which have since been published. He died at Oates in Essex on October 28, 1704. Voltaire - Biography François-Marie Arouet, or Voltaire, was born in 1694 in Paris, France and died 83 years later in the same city. Throughout his 83 years of life, Voltaire wrote numerous philosophical works, works in history, plays, and is considered as, next to Montesquieu, Locke, Rousseau and others, one of the greatest name of the French Enlightenment. He is known as a defender of religious freedom, free trade, civil liberties, social reform. He was also fighting against the limitiations of censorship, religious dogma, intolerance, and the institutions of his time. His works, and the works of fellow Enlightenment writers, influenced both the French and the American revolutions. Voltaire was the youngest of five children and, after having studied at he Collège Louis-le-Grand, decided to become a writer, against the will of his father that rather wanted to see him as a notary. This disagreement with his father was a conflict that was very present in Voltaire's early adulthood. He pretended to be working as a notary assistant in Paris, while he in fact was writing, and when his father found out, he was sent to study law. Later on, his father found him employment as the secretary of the French ambassador in the Netherlands where Voltaire fell in love with a French protestant refugee and was once more forced by his father to return to Paris. Voltaire also developed a tense relation with the authorities of the time through his critical views on religious intolerance and the governmental practices in general, views that costed him several imprisonments and exiles. In one of such imprisonments, at the Bastille, he wrote his first play entitled Œdipe, a success that sealed his reputation. It was also after the time spent at la Bastille that François-Marie Arouet adopted the pen name Voltaire, a mixture of a latinized anagram of his name and the initial letters of "the younger" (le jeune). The adoption of the name Voltaire is seen as a break from his past, specially from his family. In 1725, following an insult exchange with the French nobleman Chevalier de Rohan, Voltaire was imprisoned and, uncertain as to the duration of the sentence, suggested his own exile to Britain. In Britain, where Voltaire spent his next three years, he was curious about the country's relative freedom of speech and religion, about Shakespeare, as well as its constitutional monarchy, as opposed to the absolute monarchy of the French. His three years in Britain resulted in a collection of essays called Lettres Philosophiques sur les Anglais (Philosophical Letters on the English), released in his return to Paris which caused outrage for his defense of the British system instead of the French one and Voltaire was yet again forced to flee. This time he went to the Château de Cirey, not far from Paris, where he started a relationship with a married woman, Émilie du Châtelet, which was to last for 15 years. The Marquise and Voltaire owed a big collection of books ans studied them together experimenting with natural science, reading physics, history, and philosophy. Voltaire's essay Eléments de la philosophie de Newton (Elements of Newton's Philosophy), which was most likely written in partnership with the Marquise, is seen as the work that made accessible Newton's gravitational theory. It was also still at the Châteu de Cirey that Voltaire wrote his Essay upon the Civil Wars in France which is one of his first works to attack what he saw as the intolerance of the religious establishments, as well as to propose the separation of the church and the state. Bored at the life at the château and in love with his niece, Voltaire decided to return to Paris. The king Frederick the Great, and admirer of Voltaire's work, invited him to Potsdam and offered him a substantial salary. In Potsdam Voltaire wrote perhaps one of the first science-fiction novels involving representatives from other planets looking at humans on earth. But his tranquility wasn't to last. Following a controversy with Maupertuis, the president of the Berlin Academy of Science, Voltaire was banned by Frederick the Great and left to Paris where he was once again banned, this time by king Louis XV. He finally landed in Geneva where he purchased a big estate, called Les Délices. In Geneva he didn't last long as the local law forbid theater performances and by the end of 1758 he moved to Ferney, just across the French border, where he wrote Candide, ou l'Optimisme (Candide, or Optimism), a satirical work on the philosophy of Leibniz which is known to be one of his greatest works. In 1764, still in Ferney, he published Dictionnaire Philosophique, his most important philosophical work. At the same time Voltaire became more and more involved in the defense of people unjustly persecuted by the church. After 20 years away from Paris, Voltaire finally resolved to return and see the premiere of his latest tragedy Irene. But a five day trip was a too tortuous venture for an aging man and Voltaire, expected to die soon, wrote the farewell words "I die adoring God, loving my friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition." He nevertheless survived and succeeded in attending the performance of Irene, only to die two months later, on the 30th of May 1778. In his second farewell he said "For God's sake, let me die in peace." He was denied a proper burial by the church but his friends managed to bury him at the abbey of Scellières. In 1791 the National Assembly, which saw him as one of the forerunners of the French revolution, had his body transported to the Panthéon in Paris, in a procession that attracted an estimate one million people. Voltaire's writings in history challenged the common conception at the time that historiography dealt with big political, military, and diplomatic events. He instead emphasized in the cultural history, the arts, the sciences, the customs. He is known to be the first thinker to try to write a history of the world based on cultural, political and economic facts rejecting any kind of theological framework. Voltaire's works on history, most notably The Age of Louis XIV (1751), and Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756) helped to deviate historiography from the narration of great deeds performed by great man, of wars, and of Eurocentrism. Voltaire was also a fierce critique of religious traditions but that is not to say that he was averse to the idea of a supreme being. His understanding of God was deist, he reasoned that the existence of God was a question of reason and observation rather than of faith. In his words "It is perfectly evident to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme, and intelligent being. This is no matter of faith, but of reason." He therefore favored an understanding of God beyond institutionalized religion and defended, in A Treatise on Toleration (1763), that all men are brothers, regardless of religion, as they are the same creature created by the same God. As for slavery, Voltaire in one hand harshly criticized it and in the other hand, together with fellow philosophers Guillaume Thomas Raynal, Denis Diderot, and Buffon, he speculated and tried to explain that the different races had separate origins and at times seemed to doubt that black people possessed the same intelligence as white people. He has also been charged as an anti-semite although most of his critiques are actually directed towards religion as such and the bible, rather than Judaism in specific. Voltaire also wrote plays, prose, and poetry. His most famous play is Œdipe, an adaptation of Oedipus the King, by Sophocles, where he tried to rationalize the motivations of the characters of the original work. His major poetic works are Henriade and The Maid of Orleans, although critics point out that his minor pieces are of superior quality. In Candide, his most famous work of prose, Voltaire develops a critique of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz's philosophy of metaphysical optimism through the naive main character Candide, that after a misfortune start rejecting metaphysical optimism. Charles de Secondat, Baron de la Brède et de Montesquieu (1689-1755) BARON DE MONTESQUIEU Charles Louis de Secondat was born in Bordeaux, France, in 1689 to a wealthy family. Despite his family's wealth, de Decondat was placed in the care of a poor family during his childhood. He later went to college and studied science and history, eventually becoming a lawyer in the local government. De Secondat's father died in 1713 and he was placed under the care of his uncle, Baron de Montesquieu. The Baron died in 1716 and left de Secondat his fortune, his office as president of the Bordeaux Parliament, and his title of Baron de Montesquieu. Later he was a member of the Bordeaux and French Academies of Science and studied the laws and customs and governments of the countries of Europe. He gained fame in 1721 with his Persian Letters, which criticized the lifestyle and liberties of the wealthy French as well as the church. However, Montesquieu's book On the Spirit of Laws, published in 1748, was his most famous work. It outlined his ideas on how government would best work. Montesquieu believed that all things were made up of rules or laws that never changed. He set out to study these laws scientifically with the hope that knowledge of the laws of government would reduce the problems of society and improve human life. According to Montesquieu, there were three types of government: a monarchy (ruled by a king or queen), a republic (ruled by an elected leader), and a despotism (ruled by a dictator). Montesquieu believed that a government that was elected by the people was the best form of government. He did, however, believe that the success of a democracy - a government in which the people have the power - depended upon maintaining the right balance of power. Montesquieu argued that the best government would be one in which power was balanced among three groups of officials. He thought England - which divided power between the king (who enforced laws), Parliament (which made laws), and the judges of the English courts (who interpreted laws) - was a good model of this. Montesquieu called the idea of dividing government power into three branches the "separation of powers." He thought it most important to create separate branches of government with equal but different powers. That way, the government would avoid placing too much power with one individual or group of individuals. He wrote, "When the [law making] and [law enforcement] powers are united in the same person... there can be no liberty." According to Montesquieu, each branch of government could limit the power of the other two branches. Therefore, no branch of the government could threaten the freedom of the people. His ideas about separation of powers became the basis for the United States Constitution. Despite Montesquieu's belief in the principles of a democracy, he did not feel that all people were equal. Montesquieu approved of slavery. He also thought that women were weaker than men and that they had to obey the commands of their husband. However, he also felt that women did have the ability to govern. "It is against reason and against nature for women to be mistresses in the house... but not for them to govern an empire. In the first case, their weak state does not permit them to be preeminent; in the second, their very weakness gives them more gentleness and moderation, which, rather than the harsh and ferocious virtues, can make for a good environment." In this way, Montesquieu argued that women were too weak to be in control at home, but that their calmness and gentleness would be helpful qualities in making decisions in government. Jean-Jacques Rousseau – Biography Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born June 28, 1712 in Geneva and died July 2, 1778 in Ermenonville, France. He was one of the most important philosophers of the French enlightenment. He was born to Isaac Rousseau, a clock maker, and Suzanne Bernard, who tragically died only a few days after his birth. By the year 1725, Jean-Jacques Rousseau had begun an apprenticeship as an engraver. Three years later he left Geneva for Annecy, where he held several jobs as a teacher and secretary. Jean-Jacques Rousseau eventually moved to Paris, in 1742. There he met Denis Diderot and served as a contributor for his Encyclopédie, a radical magazine at the time. However, that had not been his actual intention; Jean-Jacques Rousseau planned to become a composer. He had introduced a new system of numbered notation (Dissertation sur la musique moderne), which he presented at the Académie des Sciences. Though it was rejected, Jean-Jacques Rousseau continued to compose none the less. The following two years, Jean-Jacques Rousseau worked for the French embassy in Venice. During this time he gained a great interest in Italian opera and had already written an opera himself entitled, Les Muses galantes (1742). In 1752, he then composed Le Devin du village, which earned him much praise and fame. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was also involved philosophically and wrote his first major philosophical work in 1750. From this work he earned a prize from the Academy of Dijon. The text, Discours sur les sciences et les arts, begins with a question, “The question before me is: 'Whether the Restoration of the arts and sciences has had the effect of purifying or corrupting morals.” This first discourse represents a radical critique of civilization. According to Rousseau, civilization is to be seen as a history of decay instead of progress. He does not conceive of the world as necessarily “good” per se, but rather argues for a sense of rationalism—one must attain rational knowledge in order to be able to control nature. In 1754, Jean-Jacques Rousseau returned to Geneva and (re)converted to Calvinism. One year later he published the Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes (Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men). Infamously he writes: The first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows: Beware of listening to this imposter; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody. He compares the “savages,” who live within themselves, with “social men,” who live outside themselves, and therefore, lives in and through the opinion of others. Thus, and in contrast to the first Discourse, Jean-Jacques Rousseau here considers reason to be the root of all problems, for it is precisely through reason that people are led to compare with each other. In 1761, Jean-Jacques Rousseau published the novel Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (Julie or the New Heloise), which turned out to be an immediate bestseller. In the following year, he finished Du Contrat Social, Principes du droit politique (Of the Social Contract, Principles of Political Right), one of the most influential books of republican thought. Departing with his perhaps most famous lines “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains,” Jean-Jacques Rousseau challenges the “actual law” criticized in his second Discourse by proposing a form of contract that should grant people liberty, namely “To find a form of association which may defend and protect with the whole force of the community the person and property of every associate, and by means of which each, coalescing with all, may nevertheless obey only himself, and remain as free as before.” Yet, in order to gain civil rights, people are to abandon their “natural” rights. The government of this state (ideally a small city-state such as Geneva) is to be an “intermediate body established between the subjects and the sovereign for their mutual correspondence, charged with the execution of the laws and with the maintenance of liberty both civil and political.” And it is thus subjected to the general will: “Each of us puts in common his person and his whole power under the supreme direction of the general will, and in return we receive every member as an indivisible part of the whole.” Though Jean-Jacques Rousseau never condemned religion per se, in the Contrait he argues in favour of a “civil religion,” which should support the unification of the state. After dividing religion into three forms, the “religion of man,” which is personal, the “religion of the citizen,” which is public, and the third, including Christianity, which he criticizes, has two competing systems of laws, namely state and religion. He then continues to outline the “dogmas of civil religion,” which “ought to be few, simple, and exactly worded, without explanation or commentary. The existence of a mighty, intelligent and beneficent Divinity, possessed of foresight and providence, the life to come, the happiness of the just, the punishment of the wicked, the sanctity of the social contract and the laws: these are its positive dogmas. Its negative dogmas I confine to one, intolerance, which is a part of the cults we have rejected.” Only one month after the publication of the Contrat, Rousseau’s next book appeared, Émile ou De l'éducation (Èmile, or on education). It was again a bestseller. In compliance with his critique of civilization (“Everything is good as it leaves the hands of the author of things, everything degenerates in the hands of man”), Jean-Jacques Rousseau elaborates on the principles of how children should be raised in order to become good citizens: What wisdom can you find that is greater than kindness? Love childhood, indulge its sports, its pleasures, its delightful instincts. Who has not sometimes regretted that age when laughter was ever on the lips, and when the heart was ever at peace? Why rob these innocents of the joys which pass so quickly, of that precious gift which they cannot abuse? Why fill with bitterness the fleeting days of early childhood, days which will no more return for them than for you? Fathers, can you tell when death will call your children to him? Do not lay up sorrow for yourselves by robbing them of the short span which nature has allotted to them. As soon as they are aware of the joy of life, let them rejoice in it, go that whenever God calls them they may not die without having tasted the joy of life. Given their radical and innovative nature, both the Contrat and Èmile caused major scandals and were burned in public. As a result, Jean-Jacques Rousseau had to flee. At first he went to the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel, then, by invitation from David Hume, he proceeded to England. Although he was still banned from France, Jean-Jacques Rousseau returned to the south of France in 1767 and was eventually, in 1770, allowed to settle in Paris. By this time, he had finished his autobiography Confessions, which wasn’t published until just after his death. And with this text he pioneered again developing what has become know as the autobiographical genre: “I have entered on an enterprise which is without precedent, and will have no imitator. I propose to show my fellows a man as nature made him, and this man shall be myself.” In 1772, Jean-Jacques Rousseau finished his last political work, Considérations sur le gouvernement de Pologne (Considerations on the Government of Poland, published 1782). In this text he sketches out a new constitution for Poland. Just before his death, Jean-Jacques Rousseau finished the additional autobiographical works Rousseau, juge de JeanJacque; Dialogue (Dialogues: Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques); and Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire (Reveries of the Solitary Walker). He died in 1778 just as the turmoil in France was erupting. After his death, his ideas were taken up by proponents of the Reign of Terror, but were also employed by the After his death, his ideas were taken up by proponents of the Reign of Terror, but were also employed by the later American philosophers/poets Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Among his most ardent critics were Voltaire and, much later, Karl Popper and Hannah Arendt.later American philosophers/poets Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Among his most ardent critics were Voltaire and, much later, Karl Popper and Hannah Arendt. Cesare Beccaria Cesare, Marchese (marquess) Di Beccaria Bonesana (born March 15, 1738, Milan—died November 28, 1794, Milan), Italian criminologist and economist whose Dei delitti e delle pene (Eng. trans. J.A. Farrer, Crimes and Punishment, 1880) was a celebrated volume on the reform of criminal justice. Early life Beccaria was the son of a Milanese aristocrat of modest means. From an early age, he displayed the essential traits of his character. A highly volatile temperament resulted in periods of enthusiasm followed by depression and inactivity. He was reserved and somewhat taciturn in his social contacts but placed great value on his personal and family relationships. At the age of eight he was sent to the Jesuit school in Parma. Beccaria later described the education he received there as “fanatical” and stifling to “the development of human feelings.” Although he revealed a mathematical aptitude, little in his student days gave indication of the remarkable intellectual achievements that were soon to follow. In 1758 he received a degree in law from the University of Pavia. In 1760 Beccaria’s proposed marriage to the 16-year-old Teresa Blasco encountered the obdurate opposition of his father. The following year the marriage took place without parental consent, and the young couple began their life together in poverty. The breach between father and son was ultimately repaired, and Beccaria and his wife were received into the family home. In 1762 a daughter, the first of his three children, was born. Upon completion of his formal training Beccaria returned to Milan and was soon caught up in the intellectual ferment associated with the 18thcentury Enlightenment. He joined with Count Pietro Verri in the organization of a literary society and participated actively in its affairs. In 1762 his first writing appeared, a pamphlet on monetary reform. Later he associated himself with the periodical Il Caffè, a journal modeled on the English periodical The Spectator, and contributed several anonymous essays to its pages. Criminal-law studies In 1763 Verri suggested that Beccaria next undertake a critical study of the criminal law. Although he had had no experience in the administration of criminal justice, Beccaria accepted the suggestion, and in 1764 his great work Dei delitti e delle pene was published. Almost immediately Beccaria, then only 26 years of age, became an international celebrity. The work enjoyed a remarkable success in France, where it was translated in 1766 and went through seven editions in six months. English, German, Polish, Spanish, and Dutch translations followed. The first American edition was published in 1777. Since then, translations in many other languages have appeared. Beccaria’s treatise is the first succinct and systematic statement of principles governing criminal punishment. Although many of the ideas expressed were familiar, and Beccaria’s indebtedness to such writers as the French philosopher Montesquieu (which he generously acknowledged) is clear, the work nevertheless represents a major advance in criminological thought. The argument of the book is founded on the utilitarian principle that governmental policy should seek the greatest good for the greatest number. He lashed out at the barbaric practices of his day: the use of torture and secret proceedings, the caprice and corruption of magistrates, brutal and degrading punishments. The objective of the penal system, he argued, should be to devise penalties only severe enough to achieve the proper purposes of security and order; anything in excess is tyranny. The effectiveness of criminal justice depends largely on the certainty of punishment rather than on its severity. Penalties should be scaled to the importance of the offense. Beccaria was the first modern writer to advocate the complete abolition of capital punishment and may therefore be regarded as a founder of the abolition movements that have persisted in most civilized nations since his day. Beccaria’s treatise exerted significant influence on criminal-law reform throughout western Europe. In England, the utilitarian philosopher and reformer Jeremy Bentham advocated Beccaria’s principles, and the Benthamite disciple Samuel Romilly devoted his parliamentary career to reducing the scope of the death penalty. Legislative reforms in Russia, Sweden, and the Habsburg Empire were influenced by the treatise. The legislation of several American states reflected Beccaria’s thought. Work in economics. Although nothing Beccaria achieved in later life approaches the importance of the treatise, his subsequent career was fruitful and constructive. In 1768 he accepted the chair in public economy and commerce at the Palatine School in Milan, where he lectured for two years. His reputation as a pioneer in economic analysis is based primarily on these lectures, published posthumously in 1804 under the title Elementi di economia pubblica (“Elements of Public Economy”). He apparently anticipated some of the ideas of Adam Smith and Thomas Malthus, such as the concept of division of labour and the relations between food supply and population. In 1771 he was appointed to the Supreme Economic Council of Milan and remained a public official for the remainder of his life. In his public role Beccaria became concerned with a large variety of measures, including monetary reform, labour relations, and public education. A report written by Beccaria influenced the subsequent adoption of the metric system in France. Beccaria’s later years were beset by family difficulties and problems of health. He apparently did not relish the role of celebrity. In 1766 he went to Paris, where he was warmly greeted by distinguished figures of the day, but cut short his visit because of acute homesickness. His wife died in 1774 after a period of declining health. Three months later he remarried. Property disputes initiated by his two brothers and sister resulted in litigation that distracted him for many years. Beccaria’s last months were saddened by events in France: although he had initially welcomed the French Revolution enthusiastically, he was shocked by the excesses of the Terror. Beccaria’s rationality, versatility, and insistence on the unity of knowledge were typical of the intellectual life of his time. His treatise, the most important volume ever written on criminal justice, is still profitably consulted two centuries after its first appearance . Denis Diderot - Biography Denis Diderot (October 5, 1713 – July 31, 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic and writer. Born at Langres and was schooled by Jesuits. He attended the University of Paris and was awarded a masters of art degree. An avid reader of classics like Horace and Homer, Diderot's insatiable appetite for reading and literature also extended to women, thereby disappointing his father who had hoped he would continue on into medicine or law. Instead, Diderot lived the life of a bohemian, bouncing from tutorships, freelance writing gigs also working at one time for Clement de Ris a prominent attorney and as a bookseller's hack. By 1743 he married Anne Toinette Champion although the relationship did not prosper and Diderot found a new love, Madeleine de Puisieux a fellow writer. It was in the 1740s that he also became a translator of English books which began to gain him some notoriety. Diderot is most recognized as the force behind the Encyclopédie, the foremost encyclopedia to be published in France at the eve of the French Revolution, but he also published a other works, comedies and bawdy tales as well as to assist his friend Friedrich Grimm in his collection of tales. Before the monumental task of putting together the Encyclopédie, Diderot became known for Essai sur la merite et la virtu (1745) and then the publication of Pensees philosophique (1746), a work that both atheism and Christianity alike but was still burned by the Parisian parliament. He also gained interest for his support of John Locke's theory of knowledge in his Lettres sur les aveugles (1749) where he attacked conventional morality and as a result was imprisoned at Vincennes for three months. His network of friends included Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, Claude Adrien Helvétius, Abbé Raynal, Lawrence Sterne, Jean-François Marmontel, and Michel-Jean Sedaine. In 1747, the project of what would become the massive Encyclopédie was initially offered up to Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert (a mathematician who eventually dropped out of the project) as a chance to co-edit the French translation of Chamber's Cyclopedia, or Universal Dictionary of the Arts and Science, but they were disenchanted with the material in the tome and preferred to set out to compile their own encyclopedia. The Encyclopédie was finally published in 1750s but the first edition of Encyclopédie was greatly amended by the editor, Andre Le Breton, (to Diderot's dismay) due to concerns about its content and the second full edition. This massive set of volumes at the time of publication were sold by subscription to not only wealthy individuals but they were also bought by small private libraries that gave access to the public, perhaps for a small fee. The impact of the Encyclopédie was widespread in France and Europe at large for by 1789 more than 25,000 copies had been distributed. There was talk about a distribution center in the United States through Benjamin Franklin, but there is no evidence that this came through. What Diderot accomplished was to create one of the most important books of the Eighteenth Century. For Diderot along with his contributors, the common purpose of which was "to further knowledge and, by so doing, strike a resounding blow against reactionary forces in church and state." How Diderot imagined this happening was by providing educational materials on technologies for what Proust broke down into three goals: "(a) to reach a large public; (b) to encourage research at all stages of production; and (c) to publish all the secrets of manufacturing." By researching trades and breaking down their application and uses, the makers of the Encyclopédie hoped to propel liberal economic views rather than mercantilist system that had been in place protecting guilds and craftsmen. We can see the effects of the philosophy that drove the work, one of rationalism and "faith in progress of the human mind" at play in the French Revolution, hence the towering importance of this tome. What this comes down to in the Encyclopédie itself is intellectual work, that of curating and explaining the different jobs, crafts, or otherwise known to the writers as mechanical arts. While this was not the sole concern for entries for such inquires as natural sciences were included, the largest proportion of the 2,900 plates were dedicated to technology. D'Alembert writes in the "Preliminary Discourse of the Encyclopedia" that "The discovery of the compass is no less advantageous to the human race than the explanation of the properties of the compass needle is to physics." This is first noticeable in the book by the fold out page that lays out the structure of the Encyclopédie. Following Bacon's lead, Diderot broke down human faculties by memory, reason and imagination, corresponding them to history, philosophy and poetry. In his Aristotelian diagram, a reader can see that the most worked out of these is reason and the mechanical arts and while history and poetry are present, the focus of the Encyclopédie was to explicate varying technologies as to make them understood by anyone. Also concerning the breakdown of knowledge in this diagram, it is important to note that while this organization of information was paid a great deal of attention, the articles in the Encyclopédie were still laid out alphabetically for ease of use; their category of knowledge would then be shown next to its heading. The most important way in which Diderot was able to make clear the workings of technologies within a craft or mechanical art was by supplementing the text with engravings of the tools used. It is from these engravings that we can see the beginnings of modern technological and mechanical instruction. For example, the section on agriculture represents not only a pastoral scene of hills and people in the fields, but also shows a catalog of the machinery used to do the work. The implements are not illustrated in use, but lined up categorically. Many of the plates that show technology represent the elements of each in a similar fashion although those that show the details of a craft usually show an overview of a shop in lieu of the workers in the fields. This type of explication of craft was received by some with fear that with secrets unveiled, people would lose their jobs, but Diderot writes in his Prospectus that "It is handicraft which makes the artist, and it is not in Books that one can learn to manipulate." This was part of the reason that Diderot had such problems with Chamber's Encyclopedia, for he thought Chambers was too stuck in books and hence Diderot's emphasis that his contributors visit the shops and study particular mechanical arts in depth before writing about them. The material chosen to include in the Encyclopédie and the engravings that accompany them is enough to prove it to be a groundbreaking work, but there is another element that is of particular interest to contemporary scholars. This element is the renvois which in old French means to send back. Today we are most familiar with this concept as labeled "hyperlink" and it has its basis in the Encyclopédie. For instance, in the article "Agriculture" there is a place when the reader is directed to an article on leaves to learn more about pruning." In a 2009 article concerning this fact, Michael Zimmer argues that this is not any different than so-called new media, the Internet and its applications based on hypertext and hyperlink for these connections "[allow] readers to relinquish their position as passive receivers of preorganized information, to subvert traditional knowledge structures and hierarchies, and to become active and integral participants in the production of knowledge." So while the Encyclopédie attempted to structure thought into memory, imagination and reason which was revolutionary in itself in that it explicated previously privileged information, it was also laying the groundwork for the revolutions in thought that we undergo today. At the time, however, Diderot was not able to make much of a living off of the Encyclopédie and long-time friend, Grimm appealed to Catherine of Russia who bought his library in 1765 as well as to provide him with a salary and use of the library as long as he lived. He continued to be a source of inspiration for the French revolution as Saint-Beuve remarked, "the first great writer who belonged wholly and undividedly to modern democratic society." He died of emphysema in Paris in 1784. Mary Wollstonecraft - Biography Mary Wollstonecraft was born on the 27th of April, 1759 in Spitalfield, London, England. She was a philosopher, novelist, historian, and most famous for her key role in the fight for women's rights. In her best known work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, (1792), Mary Wollstonecraft claims that the perceived idea that women are inferior to women is not due to any sort of natural inferiority, but rather to women's lack of access to education. Thus suggesting that if such situations were to be reversed, equality and a social compact founded on reason, could be achieved. It wasn't until the second half of the 20th century that her work attracted serious attention. Before that her work seemed to be overshadowed by concerns over her personal life with it's ill-fated affairs and late marriage with William Godwin, a philosopher and early anarchist. With one of Mary Wollstonecraft’s affairs, Gilbert Imlay, she had her first daughter, Fanny Imlay. With Godwin she had her second daughter who became a famous novelist under the married name Mary Shelley, who was born only 11 days before Wollstonecraft's death. Following her death, Godwin published a biography entitled Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman which ruined Wollstonecraft's reputation for more than a century by revealing her unorthodox life. Wollstonecraft's writings had to wait for the 20th century feminist movement to receive its deserved attention and she became known as one of the first feminist philosophers since. Mary Wollstonecraft was the second of six children and saw her comfortable childhood degrade slowly due to the fact that her father, Edward John Wollstonecraft, was losing his money on speculations. Her father was also a men of violent temper and is known to have beaten his wife when drunk. Mary Wollstonecraft played a maternal role for her own mother as well as for her sisters, protecting them from their father and advising them throughout their personal lives. It was the father of her childhood friend Jane Arden, a scientist and philosopher, that shaped Mary Wollstonecraft's early interest in philosophy. In 1778, tired with her life at home, Wollstonecraft got a job as Sarah Dawson's lady companion, which proved to be an unbearable job that did not last two years. Much of the inspiration for her later work Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, from 1787, was drawn from this experience. In 1780 she went back home to take care of her ill mother and soon after moved into her friend Fanny Blood's family home. With Fanny Blood, Mary Wollstonecraft made life plans that were frustrated by their economic condition. Together with Fanny Blood, Mary Wollstonecraft and her sisters opened a school in Newington Green, in order to try to make a living. Fanny Blood soon married and left, leaving the school to its failure and soon died. Her death partly inspired Mary Wollstonecraft's Mary: A Fiction, written in 1788. Following Fanny Blood's death and the failure of their school project, Mary Wollstonecraft managed a position in Ireland as the governess of the Kingsborough family. She had a terrible relationship with Lady Kingsborough but an inspiring relationship with their children from which she drew ideas for her Original Stories from Real Life, her only childrens book, published in 1788. Frustrated with the limit horizon of being a governess, Mary Wollstonecraft decided to abandon her work and become an author, a daring move since barely any women could support themselves as writers at the time. She moved to London and, with the help of Joseph Johnson, a liberal publisher, found space to work, learned German and French, translated texts, and wrote novel reviews for his periodical Analytical Review. Her intellectual interest and social circle greatly expanded in this period and it was then that she met her future husband William Godwin. She was still to have an affair with a married man, Henry Fuseli, which ended when Mary Wollstonecraft proposed a platonic relationship to the couple, sharply refused by Fuseli's wife. In response to the conservative critiques of Edmund Burke of the French Revolution, Mary Wollstonecraft wrote, in 1790, Vindications of the Rights of Men, a work that made her instantly famous and which made her, together with the end of the affair with Fuseli, decide to move to France and join the revolutionary struggle. Two years later, and based on Vindications of the Rights of Men, she wrote Vindications of the Rights of Women, which was to become her most influential work. In Paris she fell in love with the American adventurer Gilbert Imlay and, letting go of her rejection of the sexual component in relationships proposed in Vindications of the Rights of Women, she became pregnant and her first daughter, Fanny Imlay, was born in 1794. Overjoyed at being a mother, Wollstonecraft nevertheless continued writing and in the same year published An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution. Following the declaration of war on France by Britain, Imlay registered Wollstonecraft as his wife, even though they didn't officially marry, as to protect her. He eventually left her, tired of her new maternal phase, leaving her alone with a child, in the middle of the revolutionary turmoil. Searching for Imlay, Mary Wollstonecraft left to London in 1795 but was rejected by him which made her attempt suicide for the first time. She embarked on a business trip to Scandinavia with her daughter to try and recoup some of Imlay's financial losses, and eventually his heart. When she returned and found the situation unchanged, she attempted suicide a second time, in the River Thames. Slowly recovering, Mary Wollstonecraft came back to her literary life and circle, meeting once more William Godwin and both eventually fell in love with each other. When Mary Wollstonecraft became pregnant, they decided to marry, which made apparent the fact that she was never officially married to Imlay making the couple lose many of their friends. Godwin also received some criticism for having advocated in his writing the abolition of marriage. They moved into two adjoining houses so as to keep their independence and are known to have led a stable and happy married life, even if tragically short. Mary Shelley, her second daughter, was born on the 30th of August 1797 and her delivery brought an infection to Mary Wollstonecraft who only 11 days later took her life. Mary Wollstonecraft died at the early age of 38, on the 10th of September 1797. Her husband Godwin was devastated and Wollstonecraft was buried and had a memorial raised to her at the Old Saint Pancras Churchyard. Her tombstone mentions her as the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Godwin released in the following year Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman which, although portraying Wollstonecraft with compassion, nevertheless shocked many readers by revealing her suicide attempts, love affairs, and illegitimate children. Her A Vindication for the Rights of Woman remains as her most important work. It is considered one of the first feminist philosophical writings. She argues that women are essential in their role of raising the children and proposed to redefine their position in relation to men as companions, rather then wives. She claims that women are human beings that should share the same rights as men and strongly attacks thinkers like John Gregory, James Fordyce, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau the latter being famous for arguing that women should be exclusively educated for the pleasure of men. She insisted that what she observed as an apparent superficialness of mind of the women of her time was not due to any sort of natural deficiency but to the lack of education. Mary Wollstonecraft further accuses a culture where women were taught from infancy that the only thing they should care about is their beauty. Even though she advocates for equality of rights in many fields, she nevertheless stated that men were superior in strength and virtue. Virginia Woolf was one of the 20th century feminists to praise Mary Wollstonecraft's life and writings. Woolf wrote: "She is alive and active, she argues and experiments, we hear her voice and trace her influence even now among the living." Adam Smith (1723-1790) Adam Smith, c.1770 © Smith was a hugely influential Scottish political economist and philosopher, best known for his book 'The Wealth of Nations'. Adam Smith's exact date of birth is unknown, but he was baptised on 5 June 1723. His father, a customs officer in Kirkcaldy, died before he was born. He studied at Glasgow and Oxford Universities. He returned to Kircaldy in 1746 and two years later he was asked to give a series of public lectures in Edinburgh, which established his reputation. In 1751, Smith was appointed professor of logic at Glasgow University and a year later professor of moral philosophy. He became part of a brilliant intellectual circle that included David Hume, John Home, Lord Hailes and William Robertson. In 1764, Smith left Glasgow to travel on the Continent as a tutor to Henry, the future Duke of Buccleuch. While travelling, Smith met a number of leading European intellectuals including Voltaire, Rousseau and Quesnay. In 1776, Smith moved to London. He published a volume which he intended to be the first part of a complete theory of society, covering theology, ethics, politics and law. This volume, 'Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations', was the first major work of political economy. Smith argued forcefully against the regulation of commerce and trade, and wrote that if people were set free to better themselves, it would produce economic prosperity for all. In 1778, Smith was appointed commissioner of customs in Edinburgh. In 1783, he became a founding member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. He died in the city on 17 July 1790.