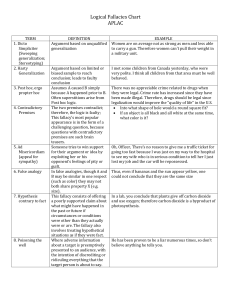

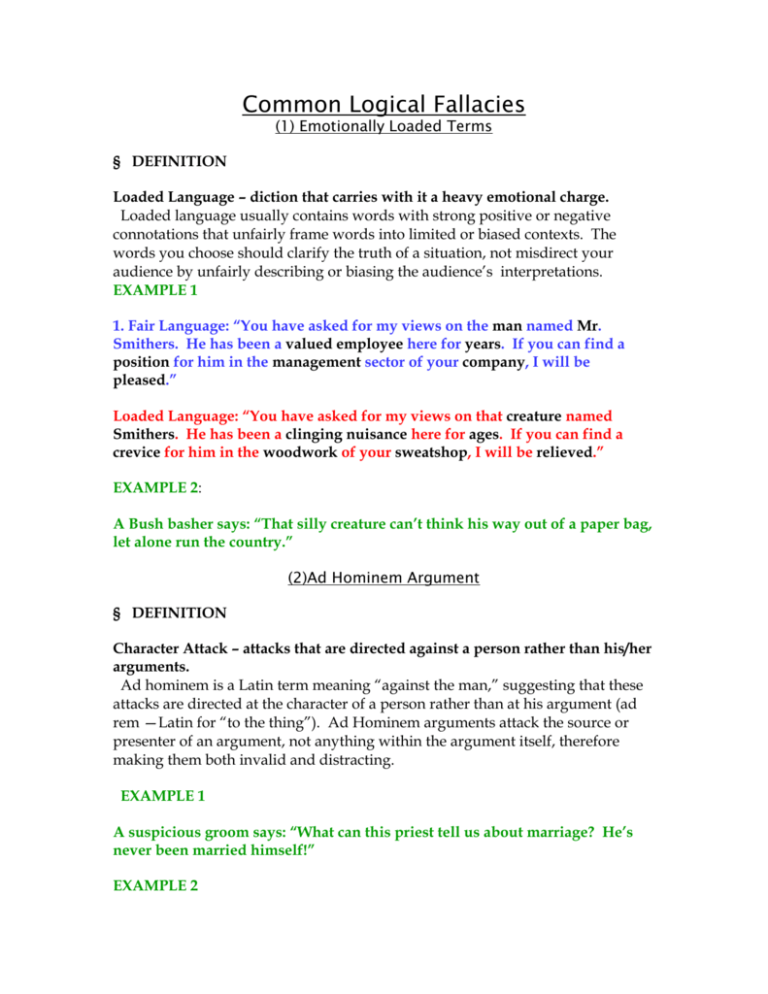

(1) Emotionally Loaded Terms

advertisement

Common Logical Fallacies (1) Emotionally Loaded Terms § DEFINITION Loaded Language – diction that carries with it a heavy emotional charge. Loaded language usually contains words with strong positive or negative connotations that unfairly frame words into limited or biased contexts. The words you choose should clarify the truth of a situation, not misdirect your audience by unfairly describing or biasing the audience’s interpretations. EXAMPLE 1 1. Fair Language: “You have asked for my views on the man named Mr. Smithers. He has been a valued employee here for years. If you can find a position for him in the management sector of your company, I will be pleased.” Loaded Language: “You have asked for my views on that creature named Smithers. He has been a clinging nuisance here for ages. If you can find a crevice for him in the woodwork of your sweatshop, I will be relieved.” EXAMPLE 2: A Bush basher says: “That silly creature can’t think his way out of a paper bag, let alone run the country.” (2)Ad Hominem Argument § DEFINITION Character Attack – attacks that are directed against a person rather than his/her arguments. Ad hominem is a Latin term meaning “against the man,” suggesting that these attacks are directed at the character of a person rather than at his argument (ad rem —Latin for “to the thing”). Ad Hominem arguments attack the source or presenter of an argument, not anything within the argument itself, therefore making them both invalid and distracting. EXAMPLE 1 A suspicious groom says: “What can this priest tell us about marriage? He’s never been married himself!” EXAMPLE 2 Fred: “All feminists hate men.” Tom: “Really?” Fred: “Yeah. That Sally chick, that girl who supervises that feminist group said that her last few boyfriends were real sexist pigs. So she thinks all men are pigs!” (3) Faulty Cause and Effect DEFINITION False Cause – identifying an improper or unrelated cause for an observed effect. Writers often state reasons for the occurrence of events or circumstances. However, these reasons must have a basis on the facts, not opinions. People often make up explanations for things that they do not understand themselves. The Latin phrase post hoc, ergo propter hoc means “after this, therefore because of this.” Just because one action or event seems to influence another, the first does not necessarily cause the second to occur. Often, coincidence is the true explanation, meaning that the two events are unrelated, and any attempt to connect these events would be rash and invalid without clear proof. This fallacy only shows up in common, every-day examples from popular culture, advertising, campaign rhetoric, etc. FOR YOUR INFORMATION We must draw conclusions based on our knowledge of the world and how it operates. For instance, when dark clouds roll across the horizon, we can conclude that it will rain very soon. We reason that the cause of rain (the clouds) will create an effect (rain) because our experience and knowledge develop this pattern. You can also reason from effect to cause: if the ground is wet (effect) then it must have rained the night before (cause). But not every cloud is a rain-making cloud. Assuming (instead of knowing) that one event must have followed another can create a cause-effect fallacy. EXAMPLE 1 Students posing as super sleuths conclude the following: “Two fellow classmates got sick right after science class; therefore, science class must have made them sick.” EXAMPLE 2 Hopefully, your doctor doesn’t tell you this: “Everyone forgets things because there is only so much room in the brain.” EXAMPLE 3 A superstitious person might say: “A black cat crossed Joe's path yesterday, and he died last night from the bad luck.” (4) Either/Or Reasoning DEFINITION Either/Or – a claim that presents an artificially limited range of choices. An either/or fallacy occurs when a speaker makes a claim (usually a premise in an otherwise valid deductive argument) that presents an artificial range of choices. For instance, he may suggest that there are only two choices possible, when three or more really exist. Those who use an either/or fallacy try to force their audience to accept a conclusion by presenting only two possible options, one of which is clearly more desirable. FOR YOUR INFORMATION These tactics are purposefully designed to seduce those who are not well informed on a given topic. A clever writer or speaker may use the either/or fallacy to make his idea look better when compared to an even worse one. This type of selective contrast is also a form of stacking the deck. This type of argument violates the principles of civil discourse: arguments should enlighten people, making them more knowledgeable and more capable of acting intelligently and independently. EXAMPLE 1 A mother may tell her child: “Eat your broccoli or you won’t get desert.” EXAMPLE 2 A firm believer states: “I'm not pro-choice; I'm pro-life.” CAUTION! Be aware: the either/or assertion does not express a pair of contradictory alternatives; rather, they offer a pair of contrary alternatives (mere contraries do not exhaust the possibilities). Light and dark, for example, are contraries because they represent opposite qualities that are necessary in one in order to define the other. Yet there are several in-between states of light in our earth: dusk, twilight, eclipses, etc. EXAMPLE 3 An ignorant friend might say: “I’m not a doctor, but your runny nose and cough tell me that you either have a cold or the flu.” EXAMPLE 4 Tony Soprano (fictional mob boss): “You either wid us or against us.” FOR YOUR INFORMATION If you claim that an argument involves false dilemma, however, the burden of proof is on you to show why the dilemma is false: be prepared to identify at least one additional, relevant option which is omitted that creates a false dilemma. NOTE: Not every either/or choice is fallacious — there may be only two reasonable alternatives. Many lights, for example, are wired so that they must exist in one of two states: on or off; likewise, a woman either is or is not pregnant, etc. (5)Hasty Generalization DEFINITION Hasty Generalization – a conclusion formed without evidence, often the product of an emotional reaction. A hasty generalization involves an over-reaction to one occurrence that grafted onto the entire group. It is the reverse of the logic used in a stereotype — a person makes a hasty generalization when he implies that all things in one group must share the traits of this one individual from the group. The resulting conclusions become mere claims without merit. The arguer must show evidence when connecting premises with conclusions to avoid making this error. FOR YOUR INFORMATION Hasty generalizations are also similar to false cause fallacies because people often think “backwards” incorrectly. We may recognize an isolated problem (one female driver cut you off on the freeway) but leap backwards from the conclusion to the premise to establish the reason: “All women are bad drivers.” To assume that her status as a woman is the reason for her questionable driving skills is a stereotype. Of course, men can also be bad drivers. This hasty generalization is probably the most prevalent of all the fallacies discussed. EXAMPLE 1 A concerned citizen says: “That man is an alcoholic. Liquor should be banned.” EXAMPLE 2 A frustrated Ford owner says: “My car broke down today! Fords are worthless pieces of garbage!” (6) False Analogy § DEFINITION False Analogy – an elaborate comparison of two things that are too dissimilar. Analogies are elaborate, point-by-point comparisons. They are most helpful when a writer is trying to explain something that is unfamiliar to his readers by explaining it in more familiar terms. Authors must compare two subjects carefully to ensure that they have essential features in common. Questionable analogies arise when a reader can point to one or more significant differences between the two subjects that are being compared in an analogy. Unfortunately, we do not have any one foolproof method of determining when analogies are legitimate or faulty. Ask yourself this key question to determine if the analogy is sound: “Do the two analogous items differ in any essential and relevant respect, or are they different only in unimportant aspects?” If the differences appear to be greater than the similarities then the analogy might be fallacious. Bear in mind that no single analogy is perfect, so this technique should be used only to illustrate foreign issues by placing them in common terms. Analogies should not be used to carry the bulk of an argument’s explanation. EXAMPLE 1 A citizen with all the answers argues: “Clogged arteries require surgery to clear them; our clogged highways require equally drastic measures.” EXAMPLE 2 A self-proclaimed expert says: “Education cannot prepare men and women for marriage. Trying to educate them for marriage is like trying to teach them to swim without allowing them to go into the water. It can’t be done.” EXAMPLE 3 Another Clinton for says: “Howard Dean has no experience of serving in the military. To have Howard Dean become president, and thus commander in chief of the armed forces of the United States, is like electing some passer-by on the street to fly the space shuttle.” (7) Begging the Question (Circular Reasoning) § DEFINITION Circular Reasoning – supporting a premise with the premise rather than a conclusion. Circular reasoning is an attempt to support a statement by simply repeating the statement in different or stronger terms. In this fallacy, the reason given is nothing more than a restatement of the conclusion that poses as the reason for the conclusion. To say, “You should exercise because it’s good for you” is really saying, “You should exercise because you should exercise.” EXAMPLE 1 A confused student argues: “You can’t give me a C. I’m an A student!” EXAMPLE 2 A satisfied citizen says: “Richardson is the most successful mayor the town has ever had because he's the best mayor of our history.” EXAMPLE 3 An obvious non-smoker blurts: “Can a person quit smoking? Of course — as long as he has sufficient willpower and really wants to quit.” (8)Non Sequitur § DEFINITION Non sequitur – a conclusion that has no apparent connection to the premises or reasons. This Latin phrase means “it does not follow” and refers to a conclusion that has no apparent connection to the reasons. Non sequiturs occur when writers omit a step in an otherwise logical chain of sequential reasoning, assuming that readers agree with the highly contestable claims of others. Two events may occur sequentially, but one may not necessarily be the cause of the other. This fallacy is part of the false cause fallacy, except that this fallacy occurs specifically due to the sequence of two unrelated events. EXAMPLE 1 A child might say to his parent: “You don’t love me or you’d buy me that bicycle!” FOR YOUR INFORMATION Non sequiturs are often found in advertising campaigns. Any car or beer commercial that associated its products with scantily clad women was implying that men should buy these products because they can somehow impress their friends or become closer to the beautiful women pictured in the ad. The warrant for the beer ad reads: “Buy this brand of beer because there is a beautiful woman holding it.” Studies show that this type of ad works wonders when targeted to men. Do men accept the logic, or does brand recognition become associated with bikinis? These commercials work on an emotional level ... but they flounder logically: it is not possible to identify an assumption that could link this reason and this conclusion in a sensible way. EXAMPLE 2 A sportscaster: “Johnson has missed his last five free throws. He’s normally an 80% shooter, so he’s got to make this one!” (9)Oversimplification (Only Reason) § DEFINITION Only Reason – identifying one valid reason, but ignoring the other possible reasons. Writers who state that there is only one reason for an occurrence, while ignoring the possibility of the existence of others, commit the only reason fallacy. No complex phenomenon can be reduced to one single simple cause. There must be other explanations, other reasons to explain an event caused by so many influences. EXAMPLE 1 A political activist says: “Poverty causes crime.” EXAMPLE 2 A history student might oversimplify its causes and effects: “The American Revolution was a revolt against the heavy tax imposed by Great Britain on imported tea.”