Argumentation/Persuasion

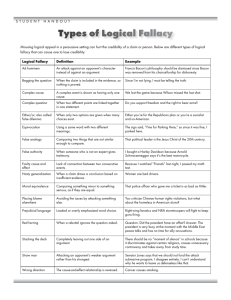

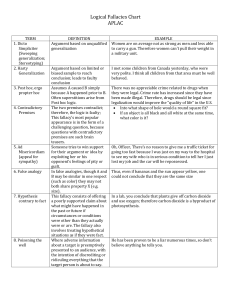

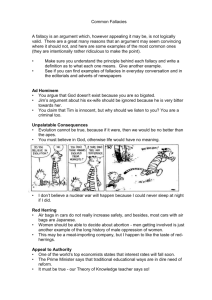

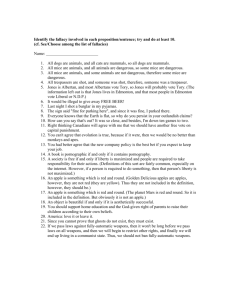

advertisement

A Research Paper is NOT… •A rearrangement or summary of information from different sources •A report that could be included in a general encyclopedia •A matter of cutting and pasting together from different resources •A result of one quick Database or Google Scholar search A Research Paper is… Your own analysis of information discovered from peer reviewed resources A chance to teach yourself something new A chance to demonstrate to others what you have learned, organized in a professional, scholarly manner Stages of Researched Writing •Choosing and Narrowing a Topic •Gathering Material: Note‐taking & Avoiding Plagiarism •Annotated Bibliography •Thesis Statement •Types of Argument •Outline •Integrating Secondary Sources: Direct Quotation, Paraphrasing, Summarizing •Works Cited Page •Title Narrowing a Topic General: Birds. Focused: The effect of deforestation on endangered bird populations in Paraguay. General: Nick in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby Focused: Symbolism associated with Nick concerning themes of love and redemption. Thesis Statement •Answers the question, “What is this paper trying to prove to its audience?” •Compresses the critical crux of your paper into one sentence. •Conveys your main argument in a nutshell. •Uses specific language and specific ideas. •Generates a multi‐faceted argument. •Appears in your paper’s introduction A Research-Based Essay • A Research Paper will utilize statistics, report findings, and expert opinion to demonstrate/support your stance on the subject. • You may want to incorporate the opposition to your topic into the essay and work on refuting their claims and dissenting views. • Refutation means pointing out the problems with the opposing viewpoints, thereby highlighting your own position’s superiority. Opposition Predict counterarguments Example: Your Argument: Organic produce from local Farmers’ Markets is better than store-bought produce. The Opposition: Organic produce is too expensive. Greek Basic Concepts of Logic: LOGOS Logos—the soundness of your argument: the facts, statistics, examples, and authoritative statements you gather to support your viewpoint. This supporting evidence must be unified, specific, adequate, accurate, and representative. Greek Basic Concepts of Logic: PATHOS Pathos—the emotional power of language: appeals to readers’ needs, values, and attitudes, encouraging them to commit themselves to a viewpoint or course of action. Connotative language—words with strong emotional overtones—can move readers to accept a point of view and may even spur them to act. Greek Concepts of Logic: ETHOS Ethos—the credibility and integrity of the argument: you cannot expect readers to accept or act on your viewpoint unless you convince them that you know what you’re talking about. Come across as knowledgeable and trustworthy by incorporating logos and taking the opposing views into account. Avoiding Plagiarism Precise note‐taking should help you avoid unintentional plagiarism, since you’ll keep secondary source information clearly distinct from your original thoughts. If the idea is not common knowledge (“the sun rises and also sets”), or not the product of your original thought processes, then cite it. Tip: If in doubt, cite! Note‐Taking When taking notes, be sure to cite your sources carefully (author, title, page numbers, publisher, publication date) and mention whether you are quoting the source verbatim (direct quotation) or summarizing a source’s ideas in your own words. Writing an Effective Research Paper Evidence/Support can be found in many ways: Which source would a reader find more credible? The New York Times http://www.myopinion.com Which person would a reader be more likely to believe? Joe Smith from Fort Wayne, IN Dr. Susan Worth, Prof. of Criminology at Purdue University Source Evaluation Questions Ask yourself the following questions to determine a source’s level of credibility: When was the source published? What are author’s credentials? Who’s the intended audience? Is the argument balanced or does it show bias and make unsupported claims, illogical conclusions, or inaccurate generalizations? Lastly, what sorts of references does your source cite? A Mnemonic Device from Dr. Robert Harris: A Good Way to Remember the Previous Slide “CAAAR”= Currency Authorship Audience Argument References Peer‐Reviewed/Refereed/Scholarly Sources: A Few Examples Electronic Sources: On‐line articles from our library’s subscription databases such as GaleNet, JSTOR and ProQuest. Print Sources: Journal articles, books. Types of Sources •Peer‐Reviewed/Scholarly/Refereed sources are by professional experts in the field. Examples: Publication of the Modern Language Association, Cell, Journal of the American Medical Association. •General‐audience sources are for non‐experts. They are written in non‐technical, accessible language. Examples: Cosmopolitan, Newsweek, Better Homes & Gardens, and many Google‐able and Yahoo‐able websites. Misrepresentation Don’t misrepresent a quote or leave out important information. Misquote: “Crime rates were down by 2002,” according to Dr. Smith. Actual quote: “Crime rates were down by 2002, but steadily began climbing again a year later,” said to Dr. Smith. Integrating Your Sources • • • For each source, you should establish the credibility of the material or person being cited. After each quote, you need to explain the material to the reader and then provide a response. By providing a response to the sourced material, you are integrating the support into your argument. Mary Sherry, owner and founder of a research and publishing firm, finds that many writers who aim to publish their work are “inadequately suffering from grammar amnesia and are deluded by a desire to be famous” (515). By this, I think she means that many of the writers today have overlooked the importance of grammar and punctuation and simply want to be recognized. This supports my stance that many writing students today. . . Quotation No‐Nos! •NO dropped quotations or quoting without proper context presented by your own thoughtful phrasing. •NO traffic‐jam quoting or choo‐chootrain quoting where several direct quotations are strung together, one after another, without discussion. Inductive Reasoning Involves examination of specific cases, facts, or examples. Based on these specifics, you then draw a conclusion or make a generalization. Evidence: My head is aching Evidence: My nose is stuffy Evidence: My throat is scratchy Conclusion: I am coming down with a cold. Deductive Reasoning Begins with a generalization that is then applied to a specific case This movement from general to specific involves a three-step form of reasoning called a syllogism: 1)Major Premise 2)Minor Premise 3)Conclusion Example of Syllogism Major Premise: In an accident, large cars are safer than small cars Minor Premise: The Hummer is a large car. Conclusion: In an accident, the Hummer will be safer than a small car. Logical Fallacies • • • • • • • • • • • Hasty Generalization Sweeping Generalization Post Hoc Fallacy (“after this, therefore because of this”) Non Sequitor Fallacy (“it does not follow”) Ad Hominen Argument (“to the man”) Appeals to Questionable or Faulty Authority Begging the Question A False Analogy Either/or Fallacy Red Herring Fallacy Appeal to Reader’s Fear or Pity Hasty Generalizations • Hasty Generalization: making a claim on the basis of inadequate evidence. • Example: It is disturbing that several of the youths who shot up schools were users of violent video games. Obviously, these games can breed violence, and they should be banned. [Most youths who play violent video games do not behave violently.] Sweeping Generalization • Absolute statements involving words such as all, always, never, and no one that allow no exceptions. • Examples: People who live in cities are unfriendly. Californians are fad-crazy Women are emotional Men can’t express their feelings [These are often considered stereoptypes] Post Hoc Fallacy • Occurs when you conclude that a causeeffect relationship exists simply because one even preceded another. • Example: A number of immigrants settle in a nearby city. The city suffers an economic decline. The immigrants’ arrival caused the decline. [This is simply co-occurrence. There are most likely other reasons for the decline.] Non-Sequitor Linking two or more ideas that in fact have no logical connection. Example: She uses a wheelchair, so she must be unhappy. [The second clause has nothing to do with the first.] Ad Hominem Attacking the qualities of the people holding an opposing view rather than the view itself. Example: Bill Clinton had extramarital affairs, so his views on global policy merit no attention. [Do the ex-president’s marital problems invalidate his political views?] Appeals to Questionable or Faulty Authority • Occurs when the argument fails to provide the credibility of the sourced material. • Examples: Sources show… An unidentified spokesperson states… Experts claim… Studies show… [If these people and reports are so reliable, they should be clearly identified.] Begging the Question Involves failure to establish proof for a debatable point. Example: The college library’s funding should be reduced by cutting subscriptions to useless periodicals. [Are some of the library’s periodicals useless?] False Analogy • Implies that because two things share some characteristics, they are therefore alike in all respects. • Example: Nicotine and marijuana involve health risks and have addictive properties. “Driving while smoking a cigarette isn’t illegal, so driving while smoking marijuana shouldn’t be illegal.” [By making this argument, you have overlooked a major difference between these two substances. Marijuana impairs perception and coordination—important aspects of driving—while there’s no evidence that nicotine does the same.] Either/or Fallacy • • Assuming that a complicated question has only two answers, one good and one bad, or both bad. Example: Either we permit mandatory drug testing in the workplace or productivity will continue to decline. [Productivity is not necessarily dependent on drug testing.] Red Herring • Introducing an irrelevant issue intended to distract readers from the relevant issues • Example: A campus speech code is essential to protect students, who already have enough problems coping with rising tuition. [Tuition costs and speech codes are different subjects. What protections do students need that a speech code will provide?] Appeal to Reader’s Fear or Pity Substituting emotions for reasoning Example: She should not have to pay taxes because she is an aged widow with no friends or relatives. [Appeals to people’s pity. Should age and loneliness, rather than income, determine a person’s tax obligation.]