Immigration Legislation History

advertisement

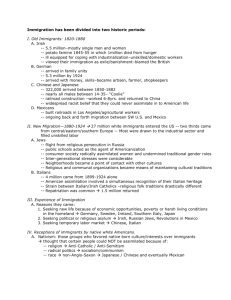

Immigration Legislation History Chinese Exclusion Act 1882 Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 Immigration Act of 1921 (aka Emergency Quota Act) Immigration Act of 1924 (aka Johnson-Reed Act)* Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (aka McCarren-Walters Act) The Chinese Exclusion Act was one of the most significant restrictions on free immigration in U.S. history. The Act excluded Chinese "skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining" from entering the country for ten years under penalty of imprisonment and deportation. Many Chinese were relentlessly beaten just because of their race. was an informal agreement between the United States and the Empire of Japan whereby the U.S. would not impose restriction on Japanese immigration, and Japan would not allow further emigration to the U.S. The goal was to reduce tensions between the two powerful Pacific nations. The agreement was never ratified by Congress, which in 1924 ended it. 3% cap of immigrant totals based on the 1910 Census (Based on that formula, the number of new immigrants admitted fell from 805,228 in 1920 to 309,556 in 1921-22). 2% cap of immigrant totals based on the 1890 Census (it further restricted Southern and Eastern Europeans and prohibited Middle Easterners, East Asians, and Asian Indians). That revised formula reduced total immigration from 357,803 in 1923–24 to 164,667 in 1924–25. The Act abolished racial restrictions found in earlier immigration statutes. It retained a quota system for nationalities and regions. Eventually, the Act established a preference system which determined which ethnic groups were desirable immigrants and placed great importance on labor qualifications. The Act defined three types of immigrants: immigrants with special skills or relatives of U.S. citizens who were exempt from quotas and who were to be admitted without restrictions; average immigrants whose numbers were not supposed to exceed 270,000 per year; refugees. Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (aka Hart-Celler Act) The Act allowed the government to deport immigrants or naturalized citizens engaged in subversive activities and also allowed the barring of suspected subversives from entering the country. It was used to bar members and former members and "fellow travelers" of the Communist Party from entry into the United States, even those who had not been associated with the party for decades. The Hart-Celler Act abolished the national origins quota system that had structured American immigration policy since the 1920s, replacing it with a preference system that focused on immigrants' skills and family relationships with citizens or residents of the U.S. Numerical restrictions on visas were set at 170,000 per year, not including immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, nor "special immigrants" (including those born in "independent" nations in the Western hemisphere; former citizens; ministers; employees of the U.S. government abroad). *Congressman Albert Johnson and Senator David Reed were the two main architects of the Immigration Act of 1924. In the wake of intense lobbying, the Act passed with strong congressional support. Proponents of the Act sought to establish a distinct American identity by favoring native-born Americans over Southern Europeans in order to "maintain the racial preponderance of the basic strain on our people and thereby to stabilize the ethnic composition of the population" Reed told the Senate that earlier legislation "disregards entirely those of us who are interested in keeping American stock up to the highest standard-that is, the people who were born here." Southern and Eastern Europeans, he believed, arrive sick and starving and therefore less capable of contributing to the American economy, and unable to adapt to American culture. Some of the law's strongest supporters were influenced by Madison Grant and his 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race. Grant was a eugenicist and an advocate of the racial hygiene theory. His data purported to show the superiority of the founding Northern European races. Most proponents of the law were rather concerned with upholding an ethnic status quo and avoiding competition with foreign workers Samuel Gompers, a Jewish immigrant and founder of the AFL, supported the Act because he opposed the cheap labor that immigration represented, despite the fact that the Act would sharply reduce Jewish immigration. President Coolidge signs the immigration act on the White House South Lawn along with appropriation bills for the Veterans Bureau. John J. Pershing is on the President's right.