Romanticism (1820 – 1900)

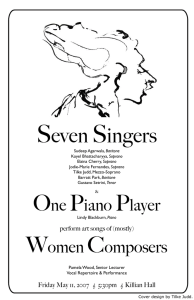

advertisement

Romanticism (1820 – 1900) The Romantic period was an age of individualism, wild imagination, rebellion against reason, and emotional expression. Painters used bolder, more brilliant colors along with dynamic motion instead of gracefully balanced poses. Painters like Francisco Goya in The Sleep of Reason Breeds Monsters show dark images such as nightmarish visions and bat-like monsters. Writers used words like painters used color with their deeper storylines, fascination with fantasy, enthusiasm for the Middle Ages and Mythology, nature, and their outlook on life with many-sided views. Writers such as Edgar Allan Poe, Mary Shelley, Charles Dickens, William Wordsworth, Walt Whitman, and Thomas De Quincy are just a few. Composers also used a greater variety of color in the music by adding instruments, greater range of dynamics, dissonant tone qualities (tone combination that is unstable and tense) as well as consonant (tone combination that is stable and restful) ones, and rubato, a speeding up and slowing down of the tempo. Composers emphasized on self-expression. It was their goal to be unique and for the music to reflect their personalities. With this individualism, a very important movement took place called Nationalism. In Nationalism, composers use individualism to deliberately created music with their specific national identity. They used folk songs, dances, legends, and history of their homeland within their music. This contrasts with the universal character of classical music. This fascination with national identity also led composers to draw on colorful materials from foreign lands. This became known as Exoticism. Composers, along with other artists, created their music with more imagination than ever before. They developed music set to a story, poem, idea, or scene to be thought about or read while the music was being performed. This style of writing was called Program Music. The music actually represents the emotions, characters, and events of a particular story, or evokes the sound and motion of nature. Pieces during this time are as diverse as possible. One piece may be written for over a hundred musicians designed for a large concert hall or opera house and last several hours in length. Another piece may be written for piano only designed to be enjoyed at home and last less than a minute. Composers began fusing each area of art into one art like never before. Their pieces took on a poetic sound, which in turn the poets wrote poems that flowed as if it were singing. Poetry and music are intimately fused in the art song, one of the most distinctive forms in romantic music. This is a composition for solo voice and piano. Yearning – inspired by lost love, nature, legend, or other times and places – haunted the imagination of romantic poets. Thus art songs are filled with these ideas. Song composers would interpret a poem, translating its mood, atmosphere, and imagery into music. Art songs are sometimes grouped in a set, or song cycle. A cycle may be unified by a story line that runs through the poems, or by musical ideas linking the songs. Although they are now performed in concert halls, art songs were written to be sung and enjoyed at home. Orchestras were becoming larger in numbers in the Romantic Period. It might include a hundred members, where in the classical period 20-60 would have been the enough. The orchestra increased as Ludwig Van Beethoven and other composers added instruments such as the bass clarinet, English horn, contrabassoon, trombone, and piccolo in the orchestra. As these instruments became standard, the progression of the brass instruments increased. The trumpets and horns now had valves and the tuba was invented in 1835 giving the composer unlimited possibilities with the brass section. The percussion section was also increased from timpani to cymbals, triangle, snare drum, bass drum, and harp. Composers Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856) in many ways personified musical romanticism. His works are intensely autobiographical, and they are usually inked with descriptive titles, texts, or programs. Schumann was born in Germany and developed a love of literature and music from a young age. This helped guide his path as an art song composer. When he was eighteen, became acquainted with his piano teacher’s nine year old daughter and prize pupil, Clara Wieck. At twenty-one, Clara went against her father and married Robert. Their marriage turned out to be a happy one that produced eight children. Clara, herself a composer, was the ideal interpreter of her husband’s piano works and introduced many of them to the public. Schumann decided to become a piano virtuoso at the late age of twenty. Around that time, he developed serious problems with the fingers of his right hand. In search for a cure, he used a mechanical gadget designed to stretch and strengthen the fingers. Instead, he was left crippled, and his hopes of being a virtuoso were crushed. It was at this point that he became a writer and composer. He discovered and made famous some of the leading composers of his day through his journal, the New Journal of Music. Robert dealt with depression his whole life, but during his forties, his mental and physical health progressively deteriorated, and in 1854 he attempted suicide by throwing himself from a bridge into the Rhine River. At his own request, he was committed to an asylum, where he died two years later. Clara Wieck Schumann (1819 – 1896) was one of the leading concert pianists of the nineteenth century. She premiered many works by her husband Robert Schumann and by her close friend Johannes Brahms. From childhood, she was trained on the piano from both her parents and between the ages of twelve and twenty, she performed throughout Europe, also usually performing one or more of her own compositions. During her fourteen-year marriage to Robert, she continued to concertize and compose – though on a reduced scale because of the seven children (one died in infancy) and take care of her very sensitive husband. One year before Robert’s attempted suicide, the Schumanns met Johannes Brahms. Robert helped Brahms to his fame by writing an article in his journal to praise this young composer. This friendship would last a lifetime. After Robert’s death, Clara expanded her performing activities, became renowned as a teacher, and edited Robert’s collected works. She stopped composing because of the predominantly negative attitude toward woman composers. Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897) was a romantic composer who breathed new life into classical forms. His intimate knowledge of past masterpieces made him extremely critical of his own work. He was obsessed by Beethoven and received criticism from Richard Wagner, but his sarcasm and rudeness helped him mask his insecurities. Once, on leaving a party, he announced, “If there is anyone here I have not insulted, I apologize!” On his first concert tour at age twenty, he met two of the greatest composers then living – Franz Liszt and Robert Schumann. Brahms did not agree with most musical matters with Liszt and stated that his music lacked form and direction. However, four weeks after performing for Robert Schumann, his name was the buzz around the musical world because of the article Robert had written about him. As Brahms was preparing new works for an eager audience, Robert was committed to an asylum, leaving Clara Schumann with seven children to support. Brahms rushed to her aid and helped her care for the children while she went on concert tours to earn money. For two years he lived in the Schumann home, becoming increasingly involved with Clara. The conflict between his loyalty to Robert and his passion for Clara may well have accounted for the stormy music he wrote at the time. Robert’s death left Brahms and Clara free to marry; yet they did not. A few months later, they separated, although they remained lifelong intimated friends. Brahms never married; for him, Clara was “the most beautiful experience of my life.” When Clara lay dying in 1896, his grief found expression in the haunting Four Serious Songs, set to biblical texts. Not long after, it was discovered that he had cancer. On March 7, 1897, he dragged himself to hear a performance of his Fourth Symphony. Less than a month later, at the age of sixty-four, he died. Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828) was one of the earliest masters of the art song, and was unlike any composer before him. He never held an official position as musical director or organist, and was neither a conductor nor a virtuoso. He was also the first Viennese composer whose income came from musical composition. Born in Vienna and the son of a schoolmaster, he loved music so much that he once sold all of his textbooks to buy a ticket for a performance of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio. He became a teacher, but soon began composing full-time. When he was seventeen, he composed his first art song, then the next year 143 songs, the next year 179 works including two symphonies, an opera, and a mass. He wrote over 600 art songs and several other works. He often lived with friends because of low income. He worked from 7 a.m. until 2 p.m., then spent his afternoons in cafes, drinking coffee, etc. Evenings were spent at “Schubertiads,” performances when only his music was played. At age 25, he contracted a venereal disease, becoming moody and prone to despair. He applied for several positions several times during his lifetime, but never received them. In 1828, a year after Beethoven’s death, Schubert died of syphilis at the age of thirty-one. Fredrick Chopin (1810 – 1849), called the poet of the piano, was the only great composer who wrote almost exclusively for the piano and the only pianist in history to have achieved a legendary reputation on the basis of only thirty or so public performances. He was a shy, reserved man who disliked crowds and preferred to play in salons rather than in public concert halls. His music reflects this in his variety of moods, and is always elegant and graceful. Chopin died at age thirty-nine of tuberculosis. Franz Liszt (1811 – 1886) was a handsome, long-haired, young man who performed superhuman feats at the piano and overwhelmed the European musical public. Irresistible to women and an incredible showman, he left a trail of broken hearts from Paris to Moscow. Paris was Liszt’s home just as it was Chopin’s. But unlike Chopin, Liszt was the master showman and preferred large crowds. To display his own incomparable piano mastery, he withdrew from the concert stage for a few years, practiced from eight to twelve hours a day, and emerged as probably the greatest pianist of his time. Liszt’s life has three periods. The first is his mastery of the piano discussed above. The second period is his composition and conducting mastery, when he completely abandoned his career as a traveling virtuoso pianist. The third period begins in 1861 when he went to Rome to pursue religious studies. The public was stunned that a “lady’s man” and virtuoso had become a churchman. With this newfound career, he composed oratorios and masses, feeling that he had a mission to reform and renew church music. Liszt is also given the credit for creating the symphonic poem, or tone poem, a one-movement orchestral composition based to some extent on literary or pictorial ideas. In essence, Liszt broke away from the typical construction of the symphony to create something new for the public. Hector Berlioz (1803 – 1869) was one of the first French romantic composers and daring creator of new orchestral sounds. He was sent to Paris to study medicine, but was horrified by the sight of blood. Instead, he began his study of music at the late age of twenty and quickly filled the gaps of his musical knowledge. When he was twenty-three, Berlioz fell in love with the works of Shakespeare and also in love with an actress by the name of Harriet Smithson. He wrote her such wild and passionate letters that she thought he was a lunatic and refused to see him. Harriet left Paris without meeting him, and Berlioz was crushed. To depict his feelings, he wrote the Symphonie fantastique (Fantastic Symphony) in 1830. In this symphony of five movements, each movement tells a story about his love that leads to a catastrophic ending of Berlioz’s life and torture. The same theme is used throughout the symphony in each movement, called a fixed idea. In Paris, Berlioz presented a concert featuring this symphony. In the audience was Harriet Smithson. When she realized that Berlioz’s music depicted her, she wanted to meet Berlioz. A year later they were married, however they separated after only a few years. Berlioz’s music is full of passionate expressiveness, inner fire, rhythmic drive, and unexpectedness. He used abrupt contrasts including dynamics, instrumentation, and tempos. Russian Five: Cesar Cui (1835 – 1918) Alexander Borodin (1833 – 1887) Mily Balakirev (1837 – 1910) Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844 – 1908) Modest Mussorgsky (1839 – 1881) These five men met together in St. Petersburg with the aim of creating a truly Russian music. They criticized each other’s works and asserted the necessity of breaking from some of the traditional techniques of German, Italian, and French composers. All had nonmusical jobs and could compose only in their spare time. Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893) is probably the most famous of all Russian composers. So rapid was his progress in music that after graduating he became professor of harmony at the new Moscow Conservatory. At age thirty, he composed his first great orchestral work, Romeo and Juliet. This sparked interest from the public in Tchaikovsky’s music. In 1877, he acquired a benefactress who supplied all of his money so that he could quit his conservatory position and devote himself strictly to composition. Tchaikovsky was a prolific composer of both instrumental and vocal works. His most popular compositions are the Forth, Fifth, and Sixth Symphonies, Romeo and Juliet, the ballet scores to Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker, and the 1812 Overture. Bedrich Smetana (1824 – 1884) was the founder of Czech national music. His works are full of folksongs, dances, and legends of his native Bohemia (which became part of Czechoslovakia). Though he was recognized as a pianist, those opposed to nationalism scorned his compositions. In 1865, he moved to Sweden, where he taught, conducted, and composed symphonic poems in the style of Franz Liszt. In 1862, he returned to Prague as an active composer, pianist, teacher, conductor, and tireless propagandist for Czech musical nationalism. At age fifty, Smetana suffered the same fate as Beethoven – he became completely deaf. Yet some of his finest works followed, including his famous symphonic poem My Country, which includes The Moldau, describing the river that runs through Czechoslovakia. He passed his last ten years in acute physical and mental torment caused by syphilis. He died in an insane asylum at age sixty. Antonin Dvorak (1841 – 1904) followed Smetana as the leading composer of Czech national music. He left home at the age of sixteen to study music in Prague. For years he earned a meager living by playing in an opera orchestra under Smetana’s direction. He was little known as a composer until his works came to the attention of the German master Brahms, who recommended Dvorak to his publisher. From this time on, his fame spread rapidly. In 1892, Dvorak went to New York, where he spent almost three years as director of the National Conservatory of Music. While here in America, he encouraged American composers to write nationalistic music. He also wrote his most famous work Symphony No. 9 (From the New Word) during his first year in America. In 1895, Dvorak returned to his homeland and lived there the rest of his life.