CASH BUDGETING

advertisement

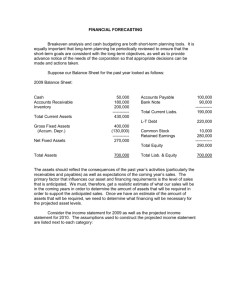

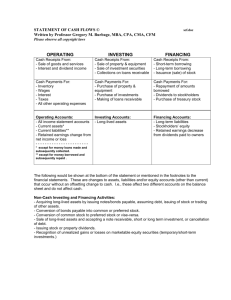

FINANCIAL FORECASTING The planning process, ideally, begins with some idealistic objective, such as producing the best product at the lowest cost. This objective, in turn, dictates that certain long-term objectives be achieved, such as developing an innovative product that can be produced in an efficient manner. Similarly, the long-term objectives require that certain short-term objectives be realized, such as generating sufficient cash flows to fund the research and development required to come up with the innovative product. Planning Short-term Objectives Intermediate-term Objectives Long-term Objectives Implementing Conversely, realizing these goals must occur in the reverse order: if a positive cash flow is not generated, there will be no funding for R&D to develop the product that you want to produce. Breakeven analysis and profit planning are short-term planning tools. In fact, many businesses do not breakeven for several years, let alone show a profit (witness many of the Internet companies). There are other tools available for evaluating such endeavors. Undoubtedly, one of the short-term objectives of such companies is to secure the financing sources required to survive until such time as a profit is realized. Critical to the success of any business, is the planning of the cash flows; i.e., cash budgeting. A budget is a plan and budgeting refers to planning. You budget your time just as you budget your cash flows. Planning is an integral part of a managementby-objective style of business management. The alternative is management-by-crisis wherein all of one’s time is spent “putting out fires” – a reactive approach to management rather than a proactive approach. The budget provides the framework by which management intends to achieve its short-term goals. For the financial manager, the cash budget aids in the performance of the job of making sure that funds are available when needed as well as planning for the efficient use of any surplus funds that exist. The ability to anticipate the financial needs of the firm allows time to find sources of funds. The complexity of the cash flows can be illustrate by the use of a simple diagram that illustrates the nature of the numerous cash inflows and outflows that confront a firm. Let the Cash Reserve box represent the checking account of the company: Intermittant Inflows (Debt, Equity) Intermittant Outflows (Taxes, Insurance, Wages) Near Cash Fixed Assets Cash Reserve Accounts Payable Accounts Receivable Cash Sales Credit Sales Inventory Into the Cash Reserve go intermittant inflows of funds from lenders and shareholders, and money flows back in the form of interest and principal payments to lenders and dividends to stockholders. There are intermittant outflows of funds to pay wages, taxes and insurance as well. Occasionally, there are tax refunds, payment on insurance claims, etc., that result in cash flows returning to the company. Near Cash (or Near Money) represents investment in short-term marketable securities so that cash surpluses can earn a rate of return. This is a where short-term surpluses of cash are “stored”. Money is spent to purchase fixed assets, which are later sold when it is time to replace them. Accounts payable must be paid. The accounts payable arise from inventory purchases which are sold to customers on either a cash basis or on credit, in which case the receivables must be collected. There are returns by our customers to us, as well as our returns to suppliers, in which case refunds are paid. As the number of suppliers, customers, lenders, etc., multiplies so does the complexity of the cash flows. Stories abound of companies that are showing a profit (in the accounting sense) but ultimately fail due to the lack of cash flow to make loan payments, pay suppliers, pay wages, taxes, and so on. Short-term Forecasting – The Cash Budget A detailed example of a cash budget is attached. A simple two-period example is presented here to illustrate the difference between the cash budgeting techniques taught in accounting courses and the cash budget utilized in finance is presented. The cash budget in finance always starts with detailing the receipts of cash. Typically, receipts are comprised of cash sales and the collection of accounts receivable. Even the collection of receivables may require a separate worksheet. Note also that if there is a 5% bad debt expense anticipated, the collections should only add up to 95%. That is, bad debt expense is not a cash outflow, it is a receipt that is not collected and, thus, not an item that appears on the cash budget since the budget only represents cash inflows and outflows. Other sources of cash inflows, such as the sale of stock that is anticipated, would also be reflected under the Receipts section of the cash budget. The next category is Disbursements where we list any and all cash payments that are to be made including salaries, rent, interest and principal payments, dividends, purchases of fixed assets, but NOT depreciation (since it is not cash) – any cash outflow that is to be made. The difference between the Receipts and Disbursements is the Net Cash Gain (Loss). The various periods for which a cash budget is being prepared can be all be done at the same time up to this point. Beyond this point in the budgeting process, however, the periods must be taken sequentially since each period depends upon the previous one. Receipts March April Cash Sales Collection of A/R 20 75 30 45 Total Receipts 95 75 35 50 15 10 0 0 35 40 15 0 20 5 110 115 Net Cash Gain (Loss) (15) (40) Plus: Beginning Cash 10 (5) Cumulative Cash (5) (45) Less: Minimum Cash (5) (5) (10) (50) Disbursements Wages Payment of A/P Rent Insurance Debt Payment Dividends Total Disbursements Surplus (Deficit) After calculating the Net Cash Gain (Loss) for each period, the Beginning Cash is added to determine the Cumulative Cash (or Ending Cash) on hand at the end of the period. This amount becomes the Beginning Cash for the following period. From the Cumulative Cash figure, we subtract the Minimum Cash that we desire to have on hand. This minimum could be a “safety stock” of cash or it could be a required amount that a lender mandates we keep available (and probably restricted in use). The remaining amount after subtracting the Minimum Cash Required is our Surplus (Deficit). Unlike the cash budgets you have probably seen before, this is a cumulative cash budget. Notice that the Surplus (Deficit) is a cumulative amount that indicates what the total position of the firm is at any point in time. Thus, our cash budget indicates that we will need $10 in financing for March and an additional $40 in April, for a total of $50 in financing requirements. The budget shows us our total financing requirements so that we can go to a bank, for example, and request a line of credit of $50 to cover our financing requirements. (Ideally, of course, the budget will also show how we intend to repay the loan as well.) The cumulative cash budget allows us to determine our total financial requirements in advance, allowing us time to find a willing supplier of funds. The only thing worse than having to find funding at the last minute, is having to go back and ask for more money at a later date. The lender will know in advance the level of commitment that must be made and, if we are turned down, we have time to line up another source of funds. Detailed Cash Budget The Simmons Company is planning to request a line of credit from its bank. following sales forecasts have been made for parts of 2009 and 2010: May 2009 June July August September October November December January 2010 The $150,000 150,000 300,000 450,000 600,000 300,000 300,000 75,000 150,000 Collection estimates obtained from the credit and collection department are as follows: collected within the month of sale, 5 percent; collected the month following the sale, 80 percent; collected the second month following the sale, 15 percent. Payments for labor and raw materials are typically made during the month following the month in which these costs are incurred. Total labor and raw materials costs are estimated for each month as follows: May 2009 June July August September October November December $ 75,000 75,000 105,000 735,000 255,000 195,000 135,000 75,000 General and administrative salaries will amount to approximately $22,500 a month; lease payments under long-term lease contracts will be $7,500 a month; depreciation charges will be $30,000 a month; miscellaneous expenses will be $2,250 a month; income tax payments of $52,500 will be due in both September and December; and a progress payment of $150,000 on a new research laboratory must be paid in October. Cash on hand on July 1 will amount to $110,000 and a minimum cash balance of $75,000 will be maintained through-out the cash budget period. A. Prepare a cash budget for the last six months of 2009 with an estimate of required financing (or excess funds). B. Assume that receipts from sales come in uniformly during the month (that is, cash payments come in at the rate of 1/30th each day), but all outflows are paid on the fifth of the month. Will this have an effect on the cash budget (i.e., will the cash budget you have prepared be valid under these assumptions)? If not, what can be done to make a valid estimate of financing requirements? Solution to Handout #8 May-09 Sales Labor & Materials Purchase Payment Jun-09 Jul-09 Aug-09 Sep-09 Oct-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 Jan-10 150,000 150,000 300,000 450,000 600,000 300,000 300,000 75,000 150,000 75,000 75,000 75,000 105,000 75,000 735,000 105,000 255,000 735,000 195,000 255,000 135,000 195,000 75,000 135,000 Collection of A/R Worksheet May-09 Jun-09 Jul-09 Aug-09 Sep-09 Oct-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 22,500 120,000 15,000 22,500 240,000 22,500 45,000 360,000 30,000 67,500 480,000 15,000 90,000 240,000 15,000 45,000 240,000 3,750 CASH BUDGET RECEIPTS Collection of Accounts Receivable Total Receipts PAYMENTS Purchases G & A Salaries Lease Payment Miscellaneous Tax Payment Progress Payment Total Payments NET CASH GAIN (LOSS) PLUS: BEGINNING CASH CUMULATIVE (ENDING) CASH 157,500 285,000 435,000 562,500 345,000 288,750 157,500 285,000 435,000 562,500 345,000 288,750 75,000 22,500 7,500 2,250 105,000 22,500 7,500 2,250 735,000 22,500 7,500 2,250 52,500 255,000 22,500 7,500 2,250 195,000 22,500 7,500 2,250 135,000 22,500 7,500 2,250 52,500 437,250 227,250 219,750 147,750 (384,750) 125,250 117,750 69,000 48,500 166,250 166,250 235,250 150,000 107,250 50,250 137,250 819,750 110,000 160,250 308,000 (76,750) 160,250 308,000 (76,750) 48,500 LESS: MINIMUM CASH BALANCE SURPLUS CASH BALANCES LOANS REQUIRED TO MAINTAIN MINIMUM CASH BALANCE 75,000 75,000 75,000 75,000 75,000 75,000 85,250 233,000 0 0 91,250 160,250 0 0 0 0 (151,750) (26,500) The detail of a cash budget is both an advantage and a hindrance to forecasting future financial requirements. The advantage is the fact that the actual timing of cash inflows and outflows is more precise than other methods and gives a more accurate picture of the firm’s financial situation, particularly when seasonality is involved. On the other hand, a lot more effort must be expended in order to develop a detailed cash budget. When a budget of short time periods is employed for forecasting purposes, the budget and income statement actually drive the construction of the projected balance sheets. To see this, consider the following one-month example: MolecuGene, Inc., is planning next month's operations and has gathered the following past and projected sales data: October November December January $80,000 60,000 50,000 55,000 40% of sales are cash sales. Of the remaining credit sales, half are collected in the first month following the sale and the rest is collected in the second month following the sale. Purchases of materials are 60% of sales and are acquired one month in advance. Purchases are paid for with cash to avoid financing charges. Staff salaries are $11,000 per month. Equipment rental fees are $1,200 per month, while MolecuGene owns the building and is depreciating it at a rate of $1,500 per month. Utilities average 5% of sales and are paid in the month following their incurrence. The Board of Directors has authorized dividends of $5,000 for common stockholders payable on December 31. The tax rate for MolecuGene is 20% and the next quarterly tax payment is due at the end of January. A. Prepare a cash budget for December indicating the surplus (deficit) of cash as of December 31. The cash balance as of November 30 is $2,000. B. Prepare a proforma income statement for December. C. The balance sheet as of November 30 is as follows: Cash $ 2,000 A/R 62,000 Inventory 45,000 Plant & Equip. Accum. Depr. Total Assets A/P (utilities) $ 3,000 Taxes/P 4,320 170,000 Common Stock 85,000 ( 50,000) Retained Earnings 136,680 $ 229,000 Tot. Liab. & Equity $ 229,000 Create a balance sheet to reflect your firm's assets and liabilities as of December 31. (Note: If your cash budget shows a surplus, additional financing will be zero. If your cash budget shows a deficit, the cash account will be zero.) Cash Budget Receipts: Cash Sales Collection of A/R October November Total Receipts $ 20,000 24,000 18,000 ($80,000 * 60% * 50%) ($60,000 * 60% * 50%) $ 62,000 Payments: Materials Purchases $ 33,000 Salaries 11,000 Equipment Rent 1,200 Utilities 3,000 Dividends 5,000 Total Payments ($50,000 * 40%) ($55,000 * 60%) ($60,000 * 5%) $ 53,200 Net Cash Gain (Loss) $ 8,800 Plus: Beginning Cash $ 2,000 Ending Cash $ 10,800 Income Statement Revenues Cost of Goods Sold $ 50,000 30,000 Gross Profit $ 20,000 Gen. & Admin. Expense Salaries Equipment Rent Depreciation Utilities $ 11,000 1,200 1,500 2,500 Total G&A $ 16,200 Operating Income (EBIT) $ 3,800 Taxes Net Income 760 $ 3,040 ($50,000 * 60%) (fixed) (fixed) (given) ($50,000 * 5%) Balance Sheet Assets Cash $ 10,800 170,000 (Beg A/R + Credit Sales – Collections = $62,000 + $30,000 - $42,000) (Beg. Inv’y + Purchases - COGS = $45,000 + $33,000 - $30,000) (No P&E bought or sold – see Inc. Stmt.) (51,500) ($50,000 + $1,500) Accounts Receivable 50,000 Inventory 48,000 Plant & Equipment Accumulated Depreciation Total Assets (From Cash Budget) $227,300 Liabilities & Equity Accounts Payable (Utilities) $ 2,500 Taxes Payable 5,080 Common Stock 85,000 Retained Earnings Total Liabilities & Equity 134,720 $227,300 (Beg. A/P + Credit Purchases – Payments = $3,000 + $2,500 - $3,000) (Beg. Tax/P + Current Taxes – Payments = $4,320 + $760 – 0) (Beg. C/S + stock sales –repurchases) (Beg. R/E + Net Income – Dividends = $136,680 + $3,040 - $5,000) Long-Term Forecasting – Percent-of-Sales or Constant Ratio Method Cash budgeting is a short-term planning tool. It is equally important that longterm planning be periodically reviewed to ensure that the short-term goals are consistent with the long-term objectives, as well as to provide advance notice of the needs of the corporation so that appropriate decisions can be made and actions taken. Suppose our Balance Sheet for the past year looked as follows: 2008 Balance Sheet: Cash Accounts Receivable Inventory Total Current Assets 50,000 180,000 200,000 -----------430,000 Accounts Payable Bank Note Total Current Liabs. 100,000 90,000 -----------190,000 L-T Debt Gross Fixed Assets (Accum. Depr.) Net Fixed Assets 400,000 (130,000) -----------270,000 Common Stock Retained Earnings Total Equity Total Assets 700,000 220,000 10,000 280,000 -----------290,000 Total Liab. & Equity The assets should reflect the consequences of the past year’s activities (particularly the receivables and payables) as well as expectations of the coming year’s sales. The primary factor that influences our asset and financing requirements is the level of sales that is anticipated. We must, therefore, get a realistic estimate of what our sales will be in the coming years in order to determine the amount of assets that will be required in order to support the anticipated sales. Once we have an estimate of the amount of assets that will be required, we need to determine what financing will be necessary for the projected asset levels. Consider the income statement for 2008 as well as the projected income statement for 2009. The assumptions used to construct the projected income statement are listed next to each category: 700,000 Income Statements: Revenues Cost of Goods Sold Gross Profit Gen. & Adm. Expense Salaries Rent Repairs & Maintenance Travel Utilities Depreciation EBIT Interest Expense Taxable Income Taxes (35%) Net Income Less: Dividends Addition to Retained Earnings 2008 Actual ====== 1,000,000 500,000 -----------500,000 2009 Projected ========= 1,200,000 600,000 -----------600,000 220,000 60,000 14,000 23,000 12,000 40,000 -----------131,000 226,600 60,000 14,420 23,690 12,360 44,000 -----------218,930 30,000 -----------101,000 30,000 -----------188,930 35,350 -----------65,650 66,126 -----------122,805 25,000 -----------40,650 25,000 -----------97,805 20% increase 50% of Sales 3% inflation Contractual 3% inflation 3% inflation 3% inflation MACRS determined If we intend to be able to meet the growing demand, we need to be sure that we have the necessary assets on hand to support our projected level of sales, as well as the ability to finance these projected asset levels. The easiest means of projecting the balance sheet is to utilize the percent-of-sales method of projection. This technique takes each account on the balance sheet that varies with sales and expresses it as a percentage of sales. This percentage is then applied to the projected sales level to determine what levels can reasonably be expected for these accounts. If we assume that the balance sheet for 2008 above was about right for the level of sales of $1 million that we experienced in 2008, then we can project the balance sheet for 2009 given our projected sales of $1.2 million for the year: Cash = $50,000 = 5% * $1,200,000 = $60,000 $1,000,000 A/R = $180,000 = 18% * $1,200,000 = $216,000 $1,000,000 Inventory = $200,000 = 20% * $1,200,000 = $240,000 $1,000,000 Fixed Assets = A/P = $400,000 = 40% * $1,200,000 = $480,000 $1,000,000 $100,000 = 10% * $1,200,000 = $120,000 $1,000,000 Note that your bank doesn’t just automatically give you more money, nor are long-term bonds automatically issued. In fact, aside from accounts payable and other accruals (which are referred to as spontaneous sources of financing) which have a zero cost, how assets are financed is a decision variable (that we will look at in detail later). Thus, simply leave these accounts alone. The only other account that is a direct function of sales is the retained earnings account which is a function of both our profitability and dividend policy. Recall the relationship between successive retained earnings accounts: Beginning R/E + Net Income – Dividends = Ending Retained Earnings $280,000 + $122,805 - $25,000 = $377,805 We now can fill in our entire projected balance sheet for 2009. Since total assets must equal total liabilities and equity, we will use Additional Financing Required as a balancing figure. 2009 Balance Sheet: Cash Accounts Receivable Inventory Total Current Assets 60,000 216,000 240,000 -----------516,000 Accounts Payable Bank Note Total Current Liabs. L-T Debt Gross Fixed Assets (Accum. Depr.) Net Fixed Assets 480,000 (174,000) -----------306,000 Common Stock Retained Earnings Total Equity Add’l Financing Req’d Total Assets 822,000 Total Liab. & Equity Ultimately, the Additional Financing Required figure must be reduced to zero. This is where decisions must be made. One source, for example may be that additional Fixed Assets are not require; i.e., there is sufficient unutilized capacity to accommodate the 20% increase in sales without any additions. This would reduce the asset requirements and, hence, the financial requirements of the firm. Another alternative might be to reduce the dividends being paid. Or additional bank loans may be taken out. In any event, we now know what our financing requirements are and we can begin looking for ways of covering our shortfall. The final step we should take is to construct the Statement of Cash Flows for 2009. It appears as follows: 2009 Statement of Cash Flows From Operations: Net Income Depreciation Operating Cash Flow Accounts Receivable Inventory Accounts Payable Working Capital Total From Operations 122,805 44,000 ----------166,805 ( 36,000) ( 40,000) 20,000 ----------( 56,000) 110,805 120,000 90,000 -----------210,000 220,000 10,000 377,805 -----------387,805 4,196 822,000 From Investment Activities: Fixed Assets Total From Investments (80,000) -----------(80,000) From Financing Activities: Additional Financing Required Dividends Total From Financing 4,196 (25,000) -----------(20,805) Total Cash Flow 10,000 Plus: Beginning Cash 50,000 Ending Cash 60,000 The figures were calculated as follows: Accounts Receivable = 180,000 – 216,000 = (36,000) Inventory = 200,000 – 240,000 = (40,000) Accounts Payable = 120,000 – 100,000 = 20,000 Fixed Assets = 400,000 – 480,000 = (80,000) Add’l Fin. Required = 4,196 – 0 = 4,196 Dividends = Beg. R/E + Net Income – End. R/E = 280,000 + 122,805 – 377,805 = (25,000) Speaking of the Fixed Assets, consider the following graph: Fixed Assets Percent-of-Sales Sales As may be observed, plant and equipment comes in “chunks” – you cannot build onefifth of a plant. Thus, sometimes the percent-of-sales approach is not the best one. As another example, consider inventories. Perhaps the best description of the relationship between inventories and sales is described by a linear (or simple) regression. Inventory (Sales) This illustrates some of the drawbacks to the percent-of-sales method. Inventory Percent-of-Sales Overestimate Linear Regression Underestimate Sales The percent-of-sales method forces the line through the origin. In the case of the inventory regression, this results in an under-estimate of the requirements at low levels of sales and an over-estimate at high levels. What would happen if we used a linear regression on Accounts Receivable?