National Nutrition Policy, 2010-2020 - Scaling Up Nutrition-SUN

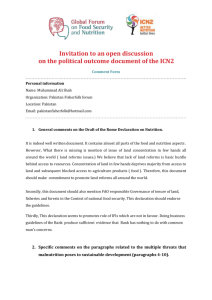

advertisement