the impossibility of love in percy shelley and machado de assis

advertisement

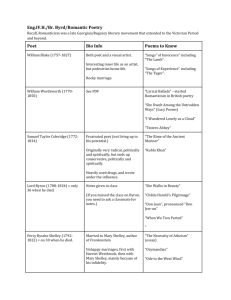

THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF LOVE IN PERCY SHELLEY AND MACHADO DE ASSIS Gentil de Faria Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Brazil The study of the literary reception of Percy Shelley (1792-1822) is still a challenging and fascinating subject that could arouse the attention of a Brazilian comparatist or a Brazilianist interested in tracing the literary reputation of foreign writers in the country. Together with Byron (1788-1824) and John Keats (1795-1821), they formed the young trinity of English romantic poetry and achieved a quite different reputation abroad. Byron, for instance, considered the lesser poet of the three, and thus labeled as a “second-rate poet”, especially by British critics¹, won a worldwide public acclaim. Whereas Keats, unanimously regarded as the best poet of the three, was hardly known to Brazilians in the nineteenthcentury. The reasons that would explain the disparity of literary fortune obtained by an author in his native country and abroad, one of the most fascinating facets of comparative studies, are many and differ in time and space. In Byron’s case², it is sufficient to mention two decisive facts: his love for personal liberty and defiance of social conventions. To explain his tremendous popularity among foreign romantic poets one should also consider the cultural impact of France upon other countries. At that time France functioned as kind of a filter of other cultures. South Americans read what was currently in fashion in Paris and therefore the French translations of Byron’s works were widely disseminated in Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires, cities that boasted of being the “Paris of the South”. Although not as popular as Byron but much more known than Keats, Shelley was widely read by Brazilian romantics. The young Álvares de Azevedo (1831-1852), for instance, an enthusiast of Byron’s poetry and one of his first translators in Brazil, picked up the refrain “No more – oh, nevermore”, from Shelley’s “A Lament”, for the epigraph of “Lembrança de morrer” [Remembrance of Dying], his most famous poem. Another line from Shelley “As almas encontram-se nos lábios dos enamorados” (Soul meets soul on lover’s lips), from Prometheus Unbound (Act IV, v. 451) has been abundantly quoted not only by poets and writers but also by ordinary people in love letters and Valentine cards, but quite often out of its original context. 2 To my knowledge, the first published translation of a Shelley’s poem in Brazil was rendered by Francisco Otaviano de Almeida Rosa (1825-1889) in his very slim book (only 43 pages), called Traduções e poesia, written in 1877, but only privately printed four years later. This very limited edition had only 50 numbered copies, and individually signed by the author. They were given to libraries and prestigious people, including Dom Pedro II, the Brazilian emperor, who received copy number one. The National Library, in Rio de Janeiro, keeps in its collection of rare books copy number 47. In these very few pages Rosa translated fragments of poems by poets as diverse as Horace, Catullus, Alexandre Dumas, Thomas Hood, and Henri Meilhac. In a chapter loosely named “Versos de Shelley”, the Brazilian poet gives his translation of Shelley as it follows: Aqui, - ali, - a Morte! – Ativa cegadora Vai ela desfechando infatigável corte Acima, abaixo, em torno, ontem, mais tarde, agora; A morte sempre em tudo! E nós somos a Morte. A sua marca e selo constantemente imprime Em tudo quanto somos, enquanto conhecemos, Naquilo que sentimos, naquilo que tememos, No Belo, - no Deforme, - na boa ação, no crime. Morre o prazer primeiro, morre a esperança após; Morre também o medo. E quando, assim, da vida Todo o interesse morre, - a dívida é devida, O pó reclama o pó, morremos também nós. (17) (Longa-Vista, 28 de novembro de 1877) It took me a great deal of time to discover the source of this untitled poem in Shelley’s immense poetical works. The original poem is “Death”, from Posthumous Poems, which reads: Death Death is here, and death is there 3 Death is busy everywhere, All around, within, beneath, Above is death - and we are death. Death has set his mark and seal On all we are and all we feel, On all we know and all we fear, First our pleasures die - and then Our hopes, and then our fears - and when These are dead, the debt is due, Dust claims dust - and we die too. All things that we love and cherish, Like ourselves, must fade and perish; Such is our rude mortal lot Love itself would, did they not. (660) This short, simple, and unfinished poem was written in 1820. The second stanza has only three lines instead of the four of the other quatrains. Surprisingly, the Brazilian translation is also incomplete but for different aspects. The last quatrain was omitted but the translator intriguingly decided to “complete” the missing line of the original second stanza by adding a strange fourth line: “No Belo, - no Deforme, - na ação, no crime”, whose equivalent is not found in the complete edition of Shelley’s works. Rosa does not explain his “contribution” to the original by adding one line that was not written by Shelley neither for the deletion of the original last stanza in his translation. Death was the favorite theme of the romantics, especially those young Brazilian poets much influenced by the French Lamartine and Musset, and the English, mainly Byron. The presence of Byron was so strong in the cultural life of Brazil that many critics called that period of literary history as “Byronism” or “Byronmania”. Comparing the original and its amputated version, one can find out that death motifs and the verb “to die” are more emphasized in the translation than in the original. In the translation “morte” (death) is personified in capital letters and its verb “morrer” is repeated four times in the last quatrain whereas it occurs only twice in the third stanza of the original poem. 4 Rosa tried to follow Shelley’s melodious rhythm and fixed rhymes. The lyrical original couplets were transformed into abab cddc effe scheme, more suitable for poetry in Portuguese. The translator also made an effort to keep the profusion of alliterations of the original poem. He was successful to translate the conciseness of the original, for instance, the line “all around, within, beneath” into “acima, abaixo, em torno, ontem, mais tarde, agora”. Though with more words but keeping the same poetic sense. Being a well-reputed journalist and a notorious politician, Rosa won an immense prestige in the decaying Royal Court of Rio de Janeiro (the Republic was proclaimed in 1889). As a poet and writer, his merits are very limited. Sílvio Romero (1851-1914), the temperamental critic and as such a Sainte-Beuve’s disciple, underrated Rosa’s literary values. “His poems”, he wrote, “are remains of a wary Classicism or shy steps into the paths of a colorless Romanticism”(875).³ With regard to Álvares de Azevedo, another Brazilian admirer of Shelley, Romero wrote that the young poet “sickened his spirit with a disorderly reading of the romantics such as Byron and Shelley” (952). Other critic, Agripino Grieco, also made caustic remarks about Rosa, whom he included under the title of “minor poets” in the Brazilian romanticism. “I do not know whether you remember this Otaviano”, he wrote. “He was a Senator of the Brazilian Empire who knew English and had attitudes of a provincial gentleman”. “Today”, Grieco adds with a sarcastic mood, “he is much depreciated, delicious in the unpremedidated poems and soporific in the poems he wrote slowly”4 (30). Although being a poet with limited merits, Rosa achieved a solid reputation as journalist and politician. He is considered the founder of the Brazilian chronicle, as a literary genre. But it is as a translator of English poets, mainly Shakespeare, Ossian, Pope, Shelley, and, above all, Byron, that he is still remembered in the studies of nineteenth-century Brazilian literature. His translations are quite elegant and as such “infidèles”. They incarnate much more of his poetic personality, deeply influenced by the Byronism of his time as a student at the Law school of São Paulo, the Mecca of a prodigious but naïve byronmania. Translations of Shelley’s works have been published in Brazil up to our days. Oswaldino Marques (1916-2003), poet, dramatist, and a perceptive critic translated three fragments of Shelley5: “A Widow Bird Sate Mourning for her Love”, (Num galho batido da invernia…), from the last lines of the drama Charles the First; “To---” (À…), a two-stanza poem from the poems written in 1821 whose first line reads: “Music, when soft voices die” 5 (Quando da música cessam as ternas vozes); and “Hymn to the Spirit of Nature” (Hino ao espírito da natureza), which are 24 lines taken from Prometheus Unbound, (act II, scene V). The first lines became famous “Life of Life! thy lips enkindle / With their love the breath between them” (Vida da Vida! Teus lábios incendeiam / De amor o alento que por eles escapa); The 544 lines of the unfinished The Triumph of Life, Shelley´s last poem, were translated in a bilingual edition in 2001.6 A Defense of Poetry was the last translation published in Brazil, some years after the Portuguese version.7 Machado de Assis Of all Brazilian writers touched by Shelley’s poetical inspiration, Machado de Assis (1839-1908) is the greatest and the one who knew better how to delve into the superb craftsmanship of the Poet’s poet, epitome that fits Shelley like a glove. In a chronicle dated 15 November 1896, writing about the transitory life of human being and the immutability of nature, Machado de Assis, in a short passage, links Shelley’s two last lines of “Mutability” (“Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like morrow; / Naught may endure but Mutability”) to line 4, chapter 1, of Ecclesiastes (“One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever”), as support for his own thoughts on the contrast between the steadiness of earth and the mobility of mankind.8 The major English influences upon Machado de Assis have been established and scanned by comparatists. In this field, his main sources include Shakespeare, Sterne, Swift, Fielding, Thackeray, and Dickens. The case with Shelley was very impressive because he created his last novel, Counselor Ayres’ Memorial, printed in Paris only three months before his death in 1908, having a single line from the poet as a recurrent motif throughout the novel. This novel represents the most autobiographical fictional work by Machado de Assis. It can be regarded as a summing up of his brilliant career as a prolific writer. It is, in fact, his literary testament. The author himself made all efforts to make sure that the novel would be the last of his works. In many occasions, especially in the letters to his circle of close friends he pointed out exhaustively his decision. For instance, in a letter (7 February 1907) to 6 Joaquim Nabuco, he wrote: “I do not know whether I will have time to shape up and put to an end a book I am meditating on and outlining it; if I can, it will be, for sure, the last”9(1078). He sent the manuscript to his friend Mario de Alencar (1872-1925), a young minor poet (he was son of José de Alencar) to whom Machado dedicated a paternal devotion. In the cover letter of 22 December 1907, he reminded Alencar, “I repeat what I said to you verbally, my dear Mario, I believe this will be my last book; strength and eyes fail to me; furthermore time is short and work is slow”10 (1084). In a letter to Joaquim Nabuco (28 June 1908), he reiterates: “In a little time Garnier will publish my book; it is the last. My age gives me neither time nor strength to start another one. I will send you a copy. I turned sixty-nine on 21st; now I enter the order of the septuagenarians”11 (1090). The printed copies of the novel sent from Paris arrived in early July. Machado speeded up the distribution to his friends. To José Veríssimo (letter of 19 July), he remarked: “The book is the last one; I am not in the age for literary follies nor for others” 12 (1090). To Joaquim Nabuco (1 August), he wrote: “There goes my Counselor Ayres’ Memorial. You will tell me what it looks like to you. I insist in saying that it is my last book; besides being weak and ill, I am getting old; I entered in the seventies, my dear friend”13 (1092). Finally, and just to give another example, Machado de Assis, on the same date of the letter before, wrote do Oliveira Lima: “This has the purpose of telling you I did not die yet – so much so that I send you a new book. I called it Counselor Ayres’ Memorial. But this new book is indeed the last. I have no strength and I am not in mood to sit down and start another one; I am old and worn-out”14 (1091). In fact, and tragically ironical, the novel was the last Machado de Assis wrote. He died two months at the dawn of 29 September 1908. As Shelley, he suffered from epilepsy, disease he was ashamed of and tried to hide even from close friends all his life. Mário de Alencar was the only confidant he trusted in that secret, but familiar to his friends who pretended not to know it. In his last letter to him (29 August) Machado said he was reading a biography of Flaubert and had discovered they suffered from the same illness, but do not mention its name. Alencar knew it already. 7 Word profaned The recurrent theme of the impossibility of love that inspired Machado de Assis to write his novel is the line 9 from the poem “To---”, which reads in full: To --ONE word is too often profaned For me to profane it, One feeling too falsely disdained For thee to disdain it; One hope is too like despair 5 For prudence to smother, And pity from thee more dear Than that from another. II I can give not what men call love, But wilt thou accept not 10 The worship the heart lifts above And the Heavens reject not, -The desire of the moth for the star, Of the night for the morrow, The devotion to something afar 16 From the sphere of our sorrow? 683) This poem was written in 1821 but only included in Posthumous Poems, published in 1824. The addressee is the “magnetic” Jane Williams, with whom Shelley was in love. The impossibility of love between them relies on the fact that both were married and their spouses were close friends. Most of Shelley’s last lyrics and verse letters, which were kept secret from Mary Shelley, his wife, had Jane as intimate confidante. Mary discovered these poems and letters after her husband’s death, drowned with Jane´s husband in mysterious circumstances. Even with a feeling of deep hurt, Mary Shelley not only preserved the originals but published them in the mentioned 1824 edition to which she wrote a very short preface where she made an effort to show no resentment towards her beloved husband. 8 “His life was spent in the contemplation of Nature, in arduous study, or in acts of kindness and affection. He was an elegant scholar and a profound metaphysician” (xi), she wrote, trying to avoid unveiling his private life and turbulent love affairs. She recalls only the poet’s male friends: Leigh Hunt and Mr. Williams. Not a single word about Jane. Fifteen years later, Mary supervised the first collected edition of her husband’s works to which she wrote a moving preface. The passing of time did not encourage her to write about intimacies, “I abstain from any remark on the occurrences is his private life /…/ This is not the time to relate the truth; and I should reject any colouring of the truth” (vii), she warns the reader from the beginning. Making an effort to be sober, and being hard working and diligent scholar, Mary classifies Shelley’s poetry in two categories: “His poems may be divided into two classes, the pure imaginative, and those which sprang from the emotions of his heart”. “The second class”, she adds, “is, of course, the more popular, as appealing at once to emotions common to all”(viii). She almost gave the key to the poem under analysis when she manages to define Shelley’s conception of love as being “exalted, absorbing, allied to all that is purest and noblest in our nature.” But she was unable to go further into the deep meaning of those poems addressed to Jane. She skips the subject that brought pain to her by saying: “Yet he was usually averse to expressing these feelings [of love], except when highly idealized; and many of more beautiful effusions he had cast aside unfinished, and they were never seen by me till after I had lost him” (viii). Although desperately in love with Jane, who made no effort to dissuade the poet from corresponding to his sentiments, Shelley sublimated his carnal passion and sex drive in this perfect lyrical Platonism. His revolt against social conventions is surrendered by his ideal of a perfect love could exist in the material world. The impossibility of love majestically condensed in the line “I can give not what men call love”, probably Shelley’s most quoted line, is twofold: his is married and loves his virtuous woman, and Jane is a married woman with his best friend. Thus not to hurt even more his beloved wife, to whom he had been unfaithful in the past, but moreover not to betray his intimate friend, Shelley chose the Platonic solution through this beautiful love-song. A witty counselor 9 Counselor Ayres’ Memorial is Machado de Assis’ most autobiographical novel. It represents the summing-up of his brilliant career as a writer who never left Brazil. He barely attended a formal school but is an astonishing example of self-education and encyclopedic knowledge despite being very poor, mulatto, motherless, short-sighted, short-sized, shy, stammerer and epileptic. Structuralist-oriented critics tend no minimize or to neglect the biographical aspects of the novel by putting emphasis solely on the inner literary qualities of the text. This attitude, however, has no grounds because the author himself admitted that the loving old Carmo, one of the major characters of the novel, was a portrait of his wife Carolina, deceased four years before. Mario de Alencar was honored with the privilege of reading the manuscript. In a letter (16 December 1907) to Machado de Assis he was the first to identify the model for the “true” and “sacred” Dona Carmo as being Carolina, “The world should admirer her [Dona Carmo] and has to admire her as an art creation; I, who guessed the model, read it moved, full of respect by the sweet evocation.”15 (257) Six days later Machado de Assis acknowledges Alencar for his favorable criticism: “The letter you sent me breathes enthusiasm that I am far from deserving it, but it is sincere and shows you have read it with soul. This is why you found the intimate model of one of the characters of the book that I tried to make it complete without a particular purpose, unless the one that evinces the human truth” (261)16 In a letter of 8 February 1908 Machado de Assis urges Alencar not to tell anybody that “secret”: “I take the opportunity to recommend you strongly, in respect of Carmo´s model, not to trust in anybody; it should remain between us”(272)17. Alencar followed the master´s appeal and reassured it in a letter of 20 February: “ I will not tell anybody that presumption I had and proved to be true on the model for Dona Carmo. In this respect your confidence was not badly used; I will do my best to correspond to such a high proof of affection” (274)18. The naïve secret between the writer and Alencar was unveiled as soon as the novel was published and released in early July. The perceptive critic José Veríssimo was the first to appoint the incarnation of Carolina in Dona Carmo ever since the copies of the novel were 10 sold in the Garnier bookstore. His letter of 18 July 1908 to Machado de Assis leaves no doubt about it. Let us quote it in full: My dear Machado have just finished reading (it is 11 AM now) your Counselor Ayres’ Memorial that I brought from Garnier yesterday. Perhaps Mário [de Alencar] would have told you I had the intention to go today, since that was not possible yesterday, to offer you my congratulations on your new book. A cold that hurt my miserable throat and so it did not allow me to have that pleasure. Accept, however, with this letter, my admiration from the bottom of my heart. What a fine and pretty book you wrote! Grant me the vanity to believe I have appreciated and understood it. Old Ayres (that is how he looks on himself.) is a good and generous fellow with the sole fault of willing to hide it. We were used to your delightful portraits of women, but believe me, you overdid with Dona Carmo. Ah, it is true that the great art does not discharge the help of heart… Get well soon, or better, recovery, life, and health, to give us the rest of the memoirs of this enchanting old who is my loveable Ayres”19 (219). Of all the many critics on Machado de Assis’ last novel, Eugênio Gomes (1897-1972) was the one who wrote more extensively on the relationship between Shelley and the Brazilian writer.20 The others merely mention the fact that Ayres quotes the poet without going into further details. Gomes not only translated the poem “To---” in prose form, but also tried to explain the “cause or obstacle” that impelled Ayres to repeat constantly that line of Shelley. To Eugênio Gomes what matters is to know whether the old diplomat was truly aroused by love in that stage of tranquil life. Although posing the question, Gomes does not give an answer to it and confines himself to point out the reincarnation of Ayres in other characters in Machado de Assis’ works. Shelley and his line are masterfully evoked six times interwoven with the plot. In the first time the poet is mentioned with the novelist Thackeray: “Spent the day leafing through 11 books, in particular, reread some Shelley, and also some Thackeray. One consoled me for the other, the other freed me from the former’s spell. Thus does genius complete genius, and the mind learn the various languages of the mind” (16) 21. As it is explicit in the text, that moment was a retaking of Shelley; it is a rereading of the poet, which indicates that Ayres was his habitual reader. The sexual attraction for the young and charming widow Fidelia arises from the beginning of the narration when Ayres saw her praying at her husband’s tomb in the cemetery. But it is from the third time on when he sees her at the old Aguiar couple’s silver wedding dinner that the old man starts depicting her sensually in terms like “I found her no less tempting than on that day in the cemetery … and no less strikingly beautiful either”, “she is pliant and soft”, “her skin is smooth and clear”, “her cheeks have a ruddy glow”. Thrown into sexual ecstasy for a dizzy moment, Ayres remembers Shelley’s line to comfort himself: No more was needed to complete a figure interesting in gesture and conversation. After the first few seconds of inspection, there is what I thought of her person. I did not immediately think in prose, but in verse as it happened, in a line of Shelley, whom I had been rereading at home, as I mentioned above, a verse from one of his stanzas of 1821: I can give not what men call love. Just so I quoted it to myself in English; but then, right after, I repeated the poet’s confession in our prose and with a close of my own composition: ´I cannot give what men call love… and it’s a pity!’(19) Ayres’ added expression to Shelley’s line (“it’s a pity!”) reinforces is conscious from the very beginning that he was not match for Fidelia. After dinner more guests arrived and old Ayres stayed in the living room watching the “alluring charm of Fidelia’s youthfulness”. For a while that line kept beating on his mind: “Shelley kept whispering in my ear, so that I could say it over to myself, ‘I can give not what men call love’” (21). He confesses his fears to his confident sister, and she said: “It was sour grapes, that is, because I feared I could not overcome the lady’s resistance, I pretended I was incapable of 12 loving. And she seized the opportunity to again pronounce a eulogy of Fidelia’s wifely devotion” (21). But the young hero Tristão comes to scene and the old diplomat had to reconcile to himself: “The eyes that I turned upon the widow Noronha were those of pure admiration, without the least notion of another sort as in the first days of this year. The truth is that even then I cited the verse from Shelley; but it is one thing to cite verses, another to believe in them” (83). Failing to accept the meaning of that line, Ayres succumbs to reality; “Although I did not then give my whole faith to the English poet, I give it to him now, and I here renew it to myself. Admiration is enough” (83). The mutual attraction of the couple is very much predictable to the reader, but the narrator refuses to face that fact by stimulating his false uncertainty: “I believe Tristão has fallen in love with Fidelia … My impression is that he has fallen in love, or he is beginning to fall in love, with the widow” (135), hardly accepting reality. Few months later, he has to recover his senses: “At last they love each other. The widow fled from him and from herself as long as she could, but now she can no longer flee. Now she appears to belong to him; she laughs with him, and on the 9th [second anniversary of her husband’s death] she will probably weep for him, unless he stops the flow of her tears with a gesture. The visits are now daily, the dinners frequent” (153). In the cemetery on the occasion of Miranda’s burial, Ayres has the idea of visiting the grave of Noronha. Shelley’s line is once again evoked, this time on the dead’s lips: “Now that the widow is about to bury him all over again, I thought it would be interesting to take a look at it, if it is not that I would have found a certain relish in attributing to the dead man the verse of Shelley’s that I had placed on my own lips, in respect to the same fair lady: I can, etc”(169). So the theme of the impossibility of love reappears: it is impossible for a dead man to love. Irony of the ironies. Ayres is invited by Tristão to be his best man. He accepts the invitation evidently “without great pleasure”. The last reconciliation with himself occurs with the wedding: “At last, married!”. Three months later the couple embarked for Lisbon. Ayres goes to say goodbye on the wharf. When he comes home, Fidelia’s image revives in his spirit and he makes an effort not to accept the reality condensed in that verse by Shelley, for the last time in the novel: 13 I will not close this page without mentioning that just now there appeared before me the figure of Fidelia, exactly as I left her on board ship, but without tears. She sat on the sofa and we looked at each other… she dissolved in charm, I giving the lie to Shelley with all the sexagenarian strength left in me.(193) The theme of the impossibility of love has been depicted by many writers since Plato. Masters include Dante, Petrarca , Camões, and the romantics. Machado de Assis, inspired by Shelley, gave a new facet to the old recurrent motif of resignation and disillusionment in the character of Ayres, an old retired widowed diplomat who, although burning with desire for the charming Fidelia, has to compromise on leaving her for the young Tristão, a reminiscent hero of the medieval narrative. 14 NOTES Earlier version of this article was delivered at the 17th Triennial Congress of the International Comparative Literature Association, August 8-15, in Hong Kong. ¹ In addition to Byron, many other British writers were higher praised in Brazil than in England. The most notorious examples are Oscar Wilde, Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, and Lewis Carroll. ² For an account of Byron´s translations and his literary fortune in Brazil, see Onédia Célia de Carvalho Barboza´s Byron no Brasil: traduções (São Paulo: Ática, 1975). The author proves through textual analysis that many of the translations in Portuguese were made indirectly from French as the source language and not English. ³ The original reads: “São restos de um classicismo estafado, ou tímidos passos na vereda de um romantismo incolor”. “Não sei se se lembram desse Otaviano... Era um senador do Império, que sabia 4 inglês e tinha atitudes de gentil-homem rural” (...) agora está depreciado ... delicioso nas poesias improvisadas e soporífero nas poesias feitas devagarinho...” 5 Marques, Oswaldino. O livro de ouro da poesia de língua inglesa. 2.ed. Rio de Janeiro: Ediouro, 1989. 6 7 O triunfo da vida. Translated by Leonardo Froes. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2001. Defesas da poesia. Trans. Enid Abreu Dobránszky. São Paulo: Iluminuras, 2002. The Portuguese translation was done by J. Monteiro-Grillo and edited by Guimarães editors. 8 Machado de Assis’s own words are: “Uma geração passa, outra geração lhe sucede, mas a terra permanece firme”(739). 9 “Não sei se terei tempo de dar forma e termo a um livro que medito e esboço; se puder, será certamente o ultimo.” 10 Repito o que lhe disse verbalmente, meu querido Mário, creio que esse será o meu último livro; faltam-me forças e olhos outros; além disso o tempo é escasso e o trabalho é lento. 11 Daqui a pouco a casa Garnier publicará um livro meu, e é o último. A idade não me dá tempo nem força de começar outro; lá lhe mandarei um exemplar. Completei no dia 21 sessenta e nove anos; entro na ordem dos septuagenários. 12 O livro é derradeiro; já não estou mais em idade de folias literárias nem outras. 15 13 Lá vai meu Memorial de Aires. Você me dirá o que lhe parece. Insisto em dizer que é o meu último livro; além de fraco e enfermo, vou adiantado em anos, entrei na casa dos setenta, meu querido amigo. 14 Esta tem por fim dizer-lhe que ainda não morri, tanto que lhe remeto um livro novo. Chamei-lhe Memorial de Aires. Mas este livro novo é deveras o último. Agora já não tenho forças nem disposição para me sentar e começar outro; estou velho e acabado. 15 O mundo poderá admirá-la e há de admirá-la como criação de arte; eu, que adivinhei o modelo, li-o comovido, cheio do respeito pela doce evocação. 16 A carta que me mandou respira toda um entusiasmo que estou longe de merecer, mas é sincera e mostra que me leu com alma. Foi também por isso que achou o modelo íntimo de uma das pessoas do livro, que eu busquei fazer completa sem designação particular, nem outra evidência que a da verdade humana. 17 “Aproveito a ocasião para lhe recomendar muito que, a respeito do modelo de Carmo, nada confie a ninguém; fica entre nós dois.” 18 “... nem a ninguém direi aquela presunção que fiz e acertou de ser verdadeira, sobre o modelo de Dona Carmo. A esse respeito a sua confiança não foi mal usada; e eu farei por corresponder a tão alta prova de afeição.” 19 “Meu caro Machado Acabo de ler (são onze horas da manhã) o seu Memorial de Ayres, que ontem trouxe da Garnier. Como talvez lhe dissesse o Mário, eu tencionava ir hoje, já que não me foi possível ir ontem mesmo, dar-lhe o meu abraço de cumprimentos pela aparição do seu novo livro. Mas um resfriado, que me atacou muito a minha miserável garganta, não me deixa ter essa satisfação. Aceite, porém, nesta aquele abraço, que é, de todo o coração, de admiração e de amor. – Que fino e belo livro você escreveu! Consinta-me a vaidade de crer que o entendi e o compreendi. O velho Ayres (é ele mesmo que se quer considerar assim) decididamente é um bom e generoso coração: apenas com o defeito de o querer esconder. Você já nos tinha acostumado às suas deliciosas figuras de mulher, mas creia-me, excedeu-se em D. Carmo. Ah! Como é verdade que a grande arte não dispensa a colaboração do coração... Desejo-lhe melhoras, ou melhor, restabelecimento e vida e saúde, para nos dar os resto do Memorial desse velho encantador que é o meu amado Aires.” (219) 20 See his “Aires e o amor” in Machado de Assis. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria S. José, 1958, p.170-174. 16 21 All quotations from Machado de Assis’ novel are taken from Counselor Ayres’ Memorial, translated by Helen Caldwell (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982). WORKS CITED Grieco, Agripino. Evolução da poesia brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Ariel, 1932. Machado de Assis. Obra completa. 8th ed. 3 vols. Rio de Janeiro: Aguilar, 1992. ---. Correspondência. Coligida e anotada por Fernando Py. Rio de Janeiro: Jackson, 1937. Romero, Sílvio. História da literatura brasileira. 6th ed. 5 vols. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1960. Rosa, Francisco Otaviano de Almeida. Traduções e poesias. Rio de Janeiro: Moreira &, Maximiliano, 1881. Shelley, Percy Bysshe. The Complete Poems with notes by Mary Shelley. New York: Modern Library, 1994. 17