Lecture 10: Multinational Corporations

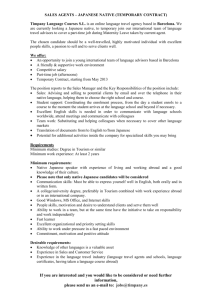

advertisement

1 Lecture 10: Multinational Corporations I. Definitions II. History: The MNC and Early U.S. Hegemony A. the spread of American capital: Good for the World? B. The MNC as an agent of U.S. Hegemony III. Explanation: Why MNCs? A. MNCs, the EC, and the Dollar B. A Liberal Economic Explanation: The product-cycle theory IV. Why do firms go abroad? A. Beating trade problems B. Avoiding Political Problems C. Low Cost Labor D. Winning technology breakthroughs VI. MNCs and Trade Negotiations: Liberals vs. Economic Nationalists VII. The Stateless Corporation? 2 MNC: Definition: A firm with production facilities in 3 or more countries. There are 16,000 MNCs in the world now. Most are small, but the top several hunderd are so huge and so globe-straddling, as to dominate major portions of the world economy. Frieden and Lake report that the 350 largest MNCs in the world with over twentyfive thousand affiliates, account for 28 per cent of the non-communist world's output. The largest MNCs have annual sales larger than the gross national product of all but a few of the world's nations. MNC and U.S. Hegemony A. The Spread of American capital: Good for the World? The story that I have been telling you here in the past few days is that the postwar capitalist world reflected American foreign policy in many of its details. A central concern of the U.S. was to build a bulwark of anti-Soviet allies; this was done with a massive inflow of American aid under the Marshall Plan, and the encouragement of Western European cooperation within a new Common market. At the same time, the United States dramatically lowered its barriers to foreign goods, and American corporations began to invest heavily in foreign nations. Remember that the U.S. was not acting altruistically; European recovery, trade liberalization, and booming international investment helped bring and ensure great prosperity within the U.S. as well. American overseas investment provided capital, technology, and experitse for both Europe and the developing world. The Non-Communist world's unprecedented access to American dollars, markets, and capital provided a major stimulus to economic growth in Europe and Japan. B. The MNC as an agent of U.S. Hegemony FDI was considered a major instrument through which the U.S. could maintain its relative position in world markets. The overseas expansion of MNCs has been regarded as a means to maintain America's dominant world economic position in other expanding economies, such as Western Europe. 3 American multiantionals have also been viewed as serving the interests of the U.S. balance of payments. The American government did not appreciate this situation until the late 1960s when the country's trading and balance of payments position first began to deterioriate. then the MNCs were recognized as major earners of foreign exchange (needed to pay for imports) MNCs also spread the ideology of the American free enterprise system. They were also a tool of diplomacy--detente with the S.U. or cut off trade. III. Why MNCs? Why do corporations go abroad? It's easy to understand why English investors would finance tea plantations in Ceylon--they couldn't grow tea in Manchester. But why does Bayer aspirin produce aspirin in the United States? If the German aspirin industry is more efficient than the American, Bayer could produce the pills in its factories at home and export them to the United States. Why does Ford make cars in England? Why does Honda make care in the U.S. (it makes a whole line of cars for export here). A. MNCs, the EC, and the Dollar The establishment of the EEC created the opportunity to go abroad, the potential revival of European industry created the fear, that if corporations didn't go abroad and establish production facilities in new markets, European industry would grow strong and become a fierce competitor. From its very inception, the Common Market was obviously an economic development of great potential significance. If American corporations wanted access to this immense market, they had to get inside the common external tariff. This process was bolstered by American's top currency status in the world during the 1950s and 1960s. Investors preferred to hold dollar-demoninated equities. Because of the security of the dollar, American firms were able to borrow on more advantegeous terms than their foriegn competitors-Foreign investment of American corporations was stimulated in part by the overvalued exchange rate of the dollar. Because of the inflated value of the dollar, foreign assets and labor were relatively cheap for American corporations. Thus the 4 system of fixed exchange rates which prevailed from 1945 to 1971 proved to be an inducement for american corporations to produce abroad rather than to export from the U.S. B. International vs. Domestic Capital FDI is considered a mechanism through which American corporations seek to enhance their own growth and profits at the expense of the rest of the American economy. Tax avoidance and the minimization of tax liabilities are critical factors in developing corporate strategy and making the decision to invest abroad. Fractions of capital--capital separates from the state Under the present U.S. tax laws, U.S. corporations are subject to a tax on foreign as well as domestic income. Extractive industries (petroleum, mining, etc.) have foreign branches; income from such branches in included in the parent corporation's tax return and the tax on such income is paid the year it is earned. But if the corporation operates through a subsid. (which is the primary case in manufacturing investment) foreign earnings are subject to a tax only when they are distributed to the U.S. Moreover, a tax credit against the domestic tax is allowed for foreign taxes paid on earnings and for dividends received from abroad. The new treaty between the U.S. and Poland allows repatriation of profits back to the U.S.--no Polish taxes. C. Liberal Explanations for MNC expansion and the role of the MNC in U.S. decline. The Product Cycle theory: (the liberal argument) The primary drive behind the overseas expansion of today's giant corporations is maximalization of corporate growth and suppression of foreign as well as domestic competition. The Product-cycly theory explains this expansion in terms of Three stages of growth: a) The innovative stage, b)the maturing phase, c)the standardized phase 1. the introductory or innovative phase: This phase is located in the most advanced industrial country or countries, such as Britain in the 19th century, the U.s. in the early postwar period, and Japan--to an increasing extent--in the late 20th century. Oligopolistic corporations in these countries have a comparative advantage in the development of new products and industrial processes due to the large home market (demand) and the resources 5 devoted to innovative activities (supply). During the initial phgase, the corporations of the most advanced economy enjoy a monopolistic position, primarily because of their technology. As foreign demand for their product rises, the corporations at first export to other markets. But as the foreign market for the product grows, and especially as the technology identified with the product diffuses abroad to potential foreign competitors, the strategy of the American corporation changes. 2. The maturing phase of the product cycle During the maturing phase the firm begins to lose the competitive advantage accruing from its technological lead. As the relevant technology becomes available through diffusion or imitative development, the advantage shifts to foreign production, owing to the proximity to the local market and lower labor costs. Therefore, if the American corporation is to maintain its market share and forstall competition, it must establish foreign branches or subsidiaries. In short, the threatened loss of an export market and the rise of foreign competitors is the stimulus for the establishment of foreign subsidiaries. (compete on their turf) 3. Finally, in the third or standardized phase of the product cycle, production has become sufficiently routinized so that the comparative advantage shifts to relatively low-skilled, low wage, and labor-intensive economies, Now the location of production shifts to less developed countries, especially the NICs, whose comparative advantage is their lower wage rates, from these export platforms, either the product itself or component parts are shipped to world markets. This is the case in textiles, electronics, and footware. Understood in these terms, direct investment and the establishement of subsidiaries abroad by American corporations is largely defensive in order to forestall the rise of foreign competitors and to maintain its global market position, the American corporation begins to manufacture abroad itself. The crux of foreign direct investment is the transference of technical and managerial knowledge, in a world where technical know-how diffuses rapidly to one's potential competitors, thereby reducing the innovator's long term profit margin. (Britain in the 19th century), the American corporation goes aborad to protect its investment in 6 research and development. Thus the American innovator, rather than the foreign imitator, captures the benefits from the trnasference of knowledge abroad. Until the late 1950s or Early 1960s, corporate expansion reflected the economic and industrial strength of the U.S. Thereafter, however, foreign idrect investment was increasingly a response to the decline of the U.S. relative to other industrial or industrializing economies. During the 1980s, Japanese investment in the U.s. increased from $10 billion annually to over $30 billion annually. By 1987 there were Japanese-owned manufacturing facilities in 40 out of the 50 states. Now, there are many arguments that increased DFI in the U.S. is a symbol that the U.S. is in decline and no longer a hegemon. Others are capturing our market and controlling our market. It is not the absolute amount of foreign investment in the U.S. economy that is a cause for concern: it is the rate of growth. In 1989, foreigners owned 4-5% of total U.S. assets. Foreign interest employed around 3 million Americans--3.5% of the labor force. At the end of 1988, according to Commerce Department data, foreigners had $1.79 trillion invested in the U.S. while Americans held $1.25 trillion in investments abroad. Whereas during the early hegemonic period, the U.S. supplied capital to the world, now the world supplies capital to the U.S. By 1986, nearly 2.3 of America's net investment in plant, equipment, and housing was being supplied by foreigners. Foreigners in recent years have financed more than half of the federal budget deficit, and they now hold 10 per cent of the national debt. Between 1986 and 1990 foreigners spent $200 billion on acquisitions and new plants. Sweden's ABB, the Netherlands' Philips, France's Thomson, and Japan's Fujitsu are waging campaigns to be identified as American companies that employ Americans, transfer technology, and help the U.S. trade balance and overall economic health. Thomson owns the RCA and General Electric brand names in consumer electronics, and Philips owns Magnovox. Why do Firms go abroad in the 1990s? 7 1. Beating Trade Problems Taiwan, South Korea, and Israel have traditionally been off-limits to Japanese auto companies. Taiwan and Korea ban importing of Japanese cars, and Japan observes the Arab embargo of Israel. But thanks to its U.S. output, Honda found a way to circumvent those problems. It ships four door Accords to Taiwan and Korea and Civic sedans to Israel, all from Ohio. The Canadian telecommunications giant Northern Telecom Ltd. Has moved so many of its manufacturing functions to the U.s. that it can win Japanese contracts on the basis of being a U.S. compnay. Japan favors the U.S. over Canadian telecommunications companies because of the politically sensitive U.S. Japanese trade gap. 2. Avoiding political problems When Germany's BASF launched biotechnology research at home, it confronted legal and political challenges from the environmentally conscious Green movement. So in 1990 BASF shifted its cancer and immune-system research to Cambridge, Mass., and plans an additional 250,000 square-foot facility in Mass. The state is attractive because of its large number of engineers and scientists but also because it has better resolved controversies involving safety, animal rights, and the environment. Biotech and cloning---German, British, and US rules 3. Low-Cost Labor. Companies still feel they might need to shift production swiftly from the U.S. and Europe to low-wage Latin American and Asia. The threat of doing so can break the back of labor in the industrialized world. When xerox Corp. started moving copier reguilding work to Mexico, its union in Rochester N.Y. objected. The risk of job loss was clear, and the union agreed to undertake the changes in work style and productivity needed to keep the jobs. 4. Winning technology breakthroughs companies are scouring the globe for leading scientific and design ideas. Xerox has introduced some 80 different office-copier models in the U.s. that were engineered and built by its Japanese joint venture, Fuji Xerox Co. And versions of the 8 superconcentrated detergent that procter and Gamble Co. first formulated in Japan in response to a rival's product are now being marketed under the Ariel brand name in Europe and tested under the Cheer and Tide labels in the U.S. What happens to trade negotiations under these conditions? Presidents have traditionally demand that foreigners open their markets to "American Products." For example, the U.S. accused Japan of excluding Motorola from the lucrative Tokyo market for celluar telephones and hinted darkly at retaliation. But it turns out that motorola designs its celluar telephones in Malaysia, and manufactures the ones it is trying to sell to Japan in Kuala Lumpur. So who benefits if the U.S. succeeds in opening the Japanese market? The liberal would say we all benefit, because japan has unfai market restrictions, and if the market is open, then the most efficient producers will benefit and consumers will benefit from buying at6 the lowest price from the cheapest producers. The Marxist would say that a handful of capitalists would benefit; those who provide managerial, financial, and strategic services to Motorola's worldwide operations, and Motorola's stockholders--most of whom are passive investors in pension funds, insurance funds, or mutual funds that own Motorola shares for a few days or hours. the investers are both foreign and American (Kautsky) The economic nationalist would say that Americans don't benefit at all, he would agree with the Marxist that just a few capitalists benefit. The economic nationalist would say that the U.S. only benefits when products are built with American labor (labor theory of value). Indeed, thousands of American workers are now making celluar telephone equipment in the U.s. for export. But the companies they make them in are Japanese. If those firms exported to Japan--and not Motorola, the U.S. would benefit. Economic nationalists say that foreing investment reduces a state's economic and political autonomy. Foreign held debt and foreign ownership imply dependence and vulnerability. With ownership goes control over economic decisions and influence over political ones. Senator Frank Murkowski (R-Alaska) summed up this view 9 bluntly in the December 30, 1985 NYT, "Once they own your assets, they own you." Foreigners' ultimate political loyalties lie elsewhere. The liberal would say, however, that FDI leads to international interdependence: Through investment, foreigners gain a direct stake in the health of the U.S. economy. The Stateless Corporation? Companies are losing their national identities (the liberal view) all over the world. Between 1987 and 1990 Coke made more money in both the Pacific and Western Europe than it did in the U.S. Nearly 70% of General Motors Corp/s 1989 profits were from non-U.S. operations. As companies begin to reap half or more of their sales and earnings from abroad, they are blending into the foreign landscape to win acceptance and avoid political hassles.