The 'knowledge boom' has hit the West like lightning in recent years

advertisement

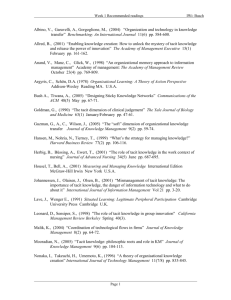

1 The 'knowledge boom' has hit the West like lightning in recent years. Its roots go way back to Plato, in 400 BC, but knowledge is heralded today as one of the newest ideas in business management. Beyond Knowledge Management: Lessons from Japan Ó June 1998 HIROTAKA TAKEUCHI Emerging from the West is a wide consensus on the strategic importance of managing knowledge well. A recent poll of executives from 80 large companies in the US, such as Amoco, Chemical Bank, Hewlett-Packard, Kodak and Pillsbury, showed that four out of five believed managing knowledge of their organisations should be an essential or important part of business strategy. These executives have also come to realise that they have a long way to go to managing knowledge well. In the same poll, only 15 per cent felt they managed knowledge well. Lewis Platt, the CEO of Hewlett-Packard, contends that successful companies of the 21st century will be those that do the best job of capturing, storing and leveraging what their employees know. He is using the phrase, "Knowledge is our currency", as a mantra to spread his message across Hewlett-Packard's worldwide Organization. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 2 CONCLUSION This paper serves as a warning to Western managers who have jumped on the "knowledge management" bandwagon. Although the growing recognition of knowledge as the critical resource is welcome news, the hoopla in the West associated with knowledge management could be a blessing in disguise. As we have seen, the focus in the West has been on (1) explicit knowledge, (2) measuring and managing existing knowledge, and (3) the selected few carrying out knowledge management initiatives. This bias reinforces the view of the Organisation simply as a machine for information processing. What Western companies need to do is to "unlearn" their existing view of knowledge and pay more attention to (1) tacit knowledge, (2) creating new knowledge, and (3) having everyone in the Organisation be involved. Only then can the Organisation be viewed as a living organism capable of creating continuous innovation in a self-organising manner. This paper has argued that knowledge holds the key to generating continuous innovation. An old concept dating back to 400 BC has emerged in the West as the newest management idea. It would be pitiful, however, if it ended up being just a buzzword or if "knowledge management" degenerated into little more than a fad, as many management concepts have done in the past. For example, re-engineering started out as a perfectly sensible management concept when first written about in 1990. But the hype which subsequently developed meant that the human factor was too quickly ignored. It would be tragic if history http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 3 repeated itself with knowledge management. WHY KNOWLEDGE? Why are managers in the West so enthralled with knowledge? Several fundamental shifts are working to fuel the knowledge movement. They include the following: • a shift to knowledge as the basic resource, • a shift to knowledge-based industries, and • a shift to growth as the top managerial priority. We will examine each below. SHIFT TO KNOWLEDGE AS THE BASIC RESOURCE Peter Drucker contends that knowledge has become the resource, rather than a resource. Knowledge has sidelined capital and labour to become the sole factor of production: "The central wealth-creating activities will be neither the allocation of capital to productive uses nor "labour"... Value is now created by "productivity" and "innovation", both applications of knowledge to work." The productivity of knowledge is going to be the determining factor in the competitive position of a company, an industry, an entire country. No country, industry, or company has any "natural" advantage or disadvantage. The only advantage it can possess is the ability to exploit universally available knowledge. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 4 Knowledge workers, who now constitute 35 per cent to 40 per cent of the workforce, will become the leading social group as a result of this shift. According to Drucker, "They will own both the 'means of production' and the 'tools of production'...the former through their pension funds, which are rapidly emerging in all developed countries as the only real owners; the latter because knowledge workers own their knowledge and can take it with them wherever they go." SHIFT TO KNOWLEDGE-BASED INDUSTRIES Knowledge-based industries are becoming the leading industries in today's economy. To quote Drucker again: "The industries that have moved into the centre of the economy in the last forty years have as their business the production and distribution of knowledge and information, rather than the production and distribution of things. The actual product of the pharmaceutical industry is knowledge,- pill and prescription ointment are no more than packaging for knowledge. There are the telecommunications industries and the industries, which produce information-processing tools and equipment, such as computers, semiconductors, and software. There are the information producers and distributors: movies, television shows, videocassettes. The "non-businesses" which produce and apply knowledge - education and health care - have in all developed countries grown much faster than even knowledge-based industries." Knowledge-based industries include both the service sector and the manufacturing sector. The service http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 5 sector includes industries where knowledge is effectively the product (such as management consulting or training) as well as industries where the product is based on the application of knowledge (such as architecture). The manufacturing sector includes industries, which produce products with high-knowledge intensity (such as packaged software), as well as those which produce products based on the application of knowledge (such as pharmaceuticals). SHIFT TO GROWTH AS THE TOP MANAGERIAL PRIORITY In the last five to seven years, Western managers focused their attention on cutting costs to the bone through downsizing and re-engineering. Recently, however, they discovered that the removal of all slack from a worker's day runs counter to creativity and innovation, which are the engines of growth. Nonaka and Takeuchi argue that Japanese companies have advanced their position in international competition because of their skills and expertise at organisational knowledge creation, which is the key to the distinctive way that Japanese companies innovate. Organisational knowledge creation is defined as the capability of a company as a whole to create new knowledge, disseminate it through the Organisation, and embody it in products, services and systems. Japanese companies, which have shunned downsizing and re-engineering for the most part, even during the recent recession, are especially good at utilising this process to bring about innovation continuously and http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 6 incrementally. The knowledge boom in the West Signs of what some call the 'knowledge boom' are visible everywhere in the Western business world today. They include new books and journals, knowledge management conferences, knowledge management services backed up by knowledge databases, and new corporate titles among other things. Consider the following: Five new books on knowledge and intellectual capital have been published in the first five months of 1997 alone, with more to come. These practitioner-oriented books on measuring and managing knowledge include the following (in alphabetical order): Verna Allee, The Knowledge Evolution Expanding Organizational Intelligence. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann, 1997 Debra M. Amidon, Innovation Strategy for the Knowledge Economy: The Ken Awakening. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann, 1997 Leif Edvinsson and Michael S. Malone, Intellectual Capital: Realizing Your Company's True Value by Finding Its Hidden Brainpower. New York: Harper Business, 1997 http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 7 Thomas A. Stewart, Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations. New York: Doubleday, 1997 Karl-Erik Sveiby, The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge-based Assets. San Francisco: Berrett Koehler, 1997. New journals, newsletters and electronic media dedicated to knowledge have been established in recent years. For example, they include the following: o Knowledge Technology Journal, published by IC' in Austin, Texas Journal of Knowledge Management, to be published by IFS International Limited in September, 1997 in London. Knowledge Inc., a newsletter published in Mountain View, California Knowledge Management Forum, an electronic conferencing medium in West Richland, Washington. Some 40 conferences on "knowledge management" were held throughout the US and Europe in 1996. Most of these conferences were organised by consulting firms, accounting firms, think tanks and management associations. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 8 The market for "knowledge management" services jumped from $US400 million in 1994 to $US2.6 billion in 1996, according to Dataquest. Consulting firms are leading the way in building "knowledge databases", which are attempts to pull scattered information throughout the organisations together and convert it into organisational memory in the form of a database. For example: Andersen Consulting set up Knowledge Xchange; Booz Allen & Hamilton developed Knowledge OnLine; Ernst & Young created their Center for Business Knowledge, KPMG Peat Marwick established A Knowledge Manage; and Price Waterhouse has Knowledge View. A new corporate title, Corporate Knowledge Officer (CKO), has been created in some 30 plus Fortune 500 companies. Some of these companies converted the Corporate Information Officer (CIO) title to the CKO title, while others are using the two simultaneously. The creation of a new title on knowledge has not been restricted to the corporate world. The academic world has followed suit as well. The first chaired professorship dedicated to the study of knowledge and its impact on business was created at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, in May 1997. The chair, named the Xerox Distinguished Professorship in Knowledge, was funded by http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 9 a donation given jointly by Fuji Xerox Co Ltd of Japan (80 per cent) and Xerox Corporation of the US (20 per cent). Ikujiro Nonaka, who holds a joint appointment at Hitotsubashi University and Japan's Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, was chosen to hold the first chaired professorship as a visiting professor. Nonaka was dubbed "Mr Knowledge" in a recent article by The Economist (31 May 1997). As evident from above, the "knowledge boom" has hit the West like lightning in recent years. Knowledge management, which Business Week defines as "the idea of capturing knowledge gained by individuals and spreading it to others in the Orga> Transfer interrupted! most popular management ideas. It contains two dimensions: Measuring knowledge (or intellectual capital), and Managing it. European companies have been international leaders in measuring knowledge, while American companies have often been cited as the leaders in managing knowledge effectively. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 10 MEASURING KNOWLEDGE European companies have taken the lead in developing measurement systems for their intangible assets and reporting the results publicly. They include (1) Skandia AFS, a subsidiary of the Skandia insurance and financial services company, (2) WM-data, a computer software and consulting company, (3) Celemi, a company that develops and sells creative training tools, and (4) PLS-Consult, a management consulting firm. All of the companies listed here are Scandinavian companies - the first three being Swedish and the fourth being Danish. They have all been influenced by the pioneering work of Karl-Erik Sveiby of Sweden, who developed a method of accounting for intangible assets in companies in the late 1980s. Collectively, these companies developed hundreds of indices and ratios in an effort to provide a comprehensive view of intellectual assets at hand. For example, these companies measure such things as "business development expenses as a percentage of total expenses", "percentage of production from new launches", "information technology investments as a percentage of total expense", "information technology employees as a percentage of total employees", "percentage of employees working directly with customers", and the like as indicators of intellectual capital. In addition, these companies actually report these indices in their annual reports to show how effectively intellectual assets are leveraged. The Skandia AFS annual report, for example, highlights the process of transforming "human capital", which is an asset the company cannot own, into "structural capital", which http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 11 can be owned by the company. Human capital is defined as the combined knowledge, skill, innovativeness and ability of the company's individual employees to meet the task at hand. It also includes the company's values, culture and philosophy. Structural capital is defined as the hardware, software, databases, organisational structure, patents, trademarks and everything else of organisational capability that supports those employees' productivity - in a word, everything left at the office when the employees go home. Structural capital also includes customer capital and the relationships developed with key customers. MANAGING KNOWLEDGE American companies have taken the lead in managing knowledge effectively. The best practices in service industries where knowledge is effectively the product come mostly from American management consulting firms. The roles that "intelligent interrogators" at McKinsey & Company and the "knowledge integrators" at Andersen Consulting play in managing knowledge are well documented. These knowledge managers are responsible for keeping the knowledge database orderly (e.g. Knowledge Xchange in the case of Andersen Consulting), categorising and formatting documents and deleting the obsolete. They are also charged with cajoling consultants into using the system and identifying topics that ought to become research projects. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 12 In the manufacturing industries, I have had first-hand experience working with GE and Hewlett-Packard, both of whom have received favourable press coverage in the knowledge management field. At GE, I served as one of the facilitators of its Work-Out program, which began in 1989. Work-Out exemplifies an attempt on the part of large companies to create the opportunity for hidden knowledge to be made public. Hewlett-Packard has been embarking on a number of knowledge management initiatives in recent years to create a purposeful process for capturing, storing, sharing and leveraging what employees know. One of the outcomes of this initiative is the formation of KnowledgeLinks, a program in which an internal consultancy group located at headquarters collects knowledge from one Hewlett-Packard business and translates it so that the other businesses can apply it. An on-line version of KnowledgeLinks is now available, enabling managers to receive a screenful of documents, war stories and best practices on how others have dealt with key management issues in the past - such as decreasing time-to-market, outsourcing manufacturing, managing retail channels and others. The KnowledgeLinks web sites not only provide access to what others have done, but whom to contact as well. Knowledge management in Japan http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 13 AS EVIDENT FROM THE ABOVE, the boom that has hit the West like lightning is not about knowledge per se, but about knowledge management. Europe appears to have an edge on measuring knowledge and the US on managing it. To repeat, knowledge management is about capturing knowledge gained by individuals and spreading it to others in the Organisation. Where does Japan stand with respect to knowledge management? "Nowhere" is probably the most accurate answer. Visible signs of the boom we saw in the West are nowhere to be found in Japan ... no onrush of new books and journals on knowledge management being published, no conferences being organised, no new databases being formed, and no new corporate titles being created. Neither are Japanese companies sending their managers in droves to Scandinavia to learn how knowledge is being measured, nor to the US to observe how knowledge initiatives are being managed at Hewlett-Packard, GE or 3M, as they have typically done with other new management ideas. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 14 Why are Japanese companies not jumping on the bandwagon with respect to knowledge management? It is not because they do not fully recognise the importance of knowledge as the resource and as the key source of innovation. They do, as Nonaka and Takeuchi pointed out in The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of innovation. What they are not convinced about is the value of simply measuring and managing existing knowledge in a mechanical and systematic manner. They doubt if that alone will enhance innovation. Japanese companies' reluctance to accept knowledge management reflects Ikujiro Nonaka's influence. Nonaka's thoughts about knowledge are different from the popular Western view in two respects according to The Economist: "The first is his relative lack of interest in information technology. Many American companies equate "knowledge creation" with setting up computer databases. Professor Nonaka argues that much of a company's knowledge bank has nothing to do with data, but is based on informal "on-the-job" knowledge everything from the name of a customer's secretary to the best way to deal with a truculent supplier. Many of these tidbits are stored in the brains of middle managers - exactly the people whom re-engineering http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 15 replaced with computers. The second thing that makes Professor Nonaka stand out is his insistence that companies need plenty of slack to remain creative. Nonaka seems to be posing two fundamental questions about knowledge management in the above quote. Can you measure the tidbits of knowledge stored in the brains of managers? Can you really create new knowledge by trying to micro-manage it? Nonaka draws -a clear distinction between knowledge management and knowledge creation, as illustrated by the following episode. In naming the first chaired professorship dedicated to the study of knowledge and its impact on business, the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, initially recommended the title "Xerox Distinguished Professorship of Knowledge Management." Nonaka inquired if the title could be changed to Xerox Distinguished Professorship of Knowledge Creation." As a compromise, they agreed to call it "Xerox Distinguished Professorship in Knowledge". The Japanese approach to knowledge differs from the West in a number of ways. We will highlight three fundamental differences here: http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 16 how knowledge is viewed, what companies do with knowledge, and who the key players are. To repeat, in Japan, knowledge is not viewed simply as data or information that can be stored in the computer; it also involves emotions, values, and hunches; companies do not merely "manage" knowledge, but "create" it as well; and everyone in the Organisation is involved in creating organisational knowledge, with middle managers serving as key knowledge engineers. TWO KINDS OF KNOWLEDGE There are two kinds of knowledge. One is explicit knowledge, which can be expressed in words and numbers and shared in the form of data, scientific formulae, product specifications, manuals, universal principles, and so forth. This kind of knowledge can be readily transmitted across individuals formally and systematically. This has been the dominant form of knowledge in the West. The Japanese, however, see this form as just the tip of the iceberg. They view knowledge as being primarily tacit, something not easily http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 17 visible and expressible. Tacit knowledge is highly personal and hard to formalise, making it difficult to communicate or share with others. Subjective insights, intuitions and hunches fall into this category of knowledge. Furthermore, tacit knowledge is deeply rooted in an individual's action and experience, as well as in the ideals, values or emotions he or she embraces. To be precise, there are two dimensions to tacit knowledge. The first is the "technical" dimension, which encompasses the kind of informal and hard-to-pin-down skills or crafts often captured in the term "know-how". Master craftsmen or three-star chefs, for example, develop a wealth of expertise at their fingertips, after years of experience. But they often have difficulty articulating the technical or scientific principles behind what they know. Highly subjective and personal insights, intuitions, hunches and inspirations derived from bodily experience fall into this dimension. Tacit knowledge also contains an important cognitive" dimension. It consists of beliefs, perceptions, ideals, values, emotions and mental models so ingrained in us that we take them for granted. Though they cannot be articulated very easily, this dimension of tacit knowledge shapes the way we perceive the world around us. The difference in the philosophical tradition of the West and Japan sheds light on why Western managers tend to emphasise the importance of explicit knowledge whereas Japanese managers put more emphasis on http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 18 tacit knowledge. Western philosophy has a tradition of separating "the subject who knows" from "the object that is known", epitomised in the work of the French rationalist Descartes. He proposed a concept that is called after him, the Cartesian split, which is the separation between the knower and the known, mind and body, subject and object. Descartes argued that the ultimate truth can be deduced only from the real existence of a "thinking self", which was made famous by his phrase, "I think, therefore I am." He assumed that the "thinking self" is independent of body or matter, because while a body or matter does have an extension we can see and touch but doesn't think, a mind has no extension but thinks. Thus, according to the Cartesian dualism, true knowledge can be obtained only by the mind, not the body. In contrast, the Japanese intellectual tradition placed a strong emphasis on the importance of the "whole personality", which provided a basis for valuing personal and physical experience over indirect, intellectual abstraction. This tradition of emphasising bodily experience has contributed to the development of a methodology in Zen Buddhism dubbed "the oneness of body and mind" by Eisai, one of the founders of Zen Buddhism in medieval Japan. Zen profoundly affected samurai education, which sought to develop wisdom through physical training. In traditional samurai education, knowledge was acquired when it was integrated into one's "personal character". Samurai education placed a great emphasis on building up character and attached little http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 19 importance to prudence, intelligence and metaphysics. Being a "man of action" was considered more important than mastering philosophy and literature, although these subjects also constituted a major part of samurai education. The Japanese have long emphasised the importance of bodily experience. A child learns to eat, walk and talk through trial and error. He or she learns with the body, not only with the mind. Similarly, a student of traditional Japanese art - for example, calligraphy, tea ceremony, flower arrangement or Japanese dancing - learns by imitating the moves of the master. A master becomes a master when the body and mind become one while stroking the brush (calligraphy) or pouring water into the kettle (tea ceremony). A sumo wrestler becomes a grand champion when he achieves shingi-ittai, or when the mind (shin) and technique (gi) become one (ittai). There is a long philosophical tradition in the West of valuing precise, conceptual knowledge and systematic sciences, which can be traced back to Descartes. In contrast, the Japanese intellectual tradition values the embodiment of direct, personal experience. It is these distinct traditions that account for the difference in the importance attached to explicit and tacit knowledge. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 20 KNOWLEDGE CREATION, NOT KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT The distinction between explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge is the key to understanding the differences between the Western approach to knowledge (knowledge management) and the Japanese approach to knowledge (knowledge creation). The West has placed a strong emphasis on explicit knowledge and Japan on tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge can easily be "processed" by a computer, transmitted electronically, or stored in databases. But the subjective and intuitive nature of tacit knowledge makes it difficult to process or transmit the acquired knowledge in any systematic or logical manner. For tacit knowledge to be communicated and shared within the organisation, it has to be converted into words or numbers that anyone can understand. It is precisely during the time this conversion takes place - that is, from tacit to explicit - that organisational knowledge is created. The reason why Western managers tend not to address the issue of organisational knowledge creation can be traced to the view of knowledge as necessarily explicit. They take for granted a view of the Organisation as a playing field for "scientific managements and a machine for "information processing". This view is deeply ingrained in the traditions of Western management, from Frederick Taylor to Herbert Simon. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 21 Frederick Taylor prescribed "scientific" methods for the workplace, the most important being time-and-motion studies. Time-and-motion studies encourage "a preoccupation with allocating resources, ...monitoring and measuring performance, and manipulating organisational structures to set lines of authority. Taylor developed "an arsenal of tools to promote efficiency and consistency by controlling individuals' behaviour and compelling employees to comply with management dictates. Scientific management had little to do with encouraging the active cooperation of workers. As Kim and Mauborgne point out, "Creating and sharing knowledge are intangible activities that can neither be supervised nor forced out of people. They happen only when people cooperate voluntarily. Nonaka also contends that the creation of knowledge cannot be managed. The notion of creating something new runs counter to the "control" mentality of traditional management science: "Given a certain context, knowledge emerges naturally. You will have to give your employees a lot of latitude, not try to control them," says Nonaka. He sees the experiences and judgments of employees, their commitment, their ideals and their way of life as an important source of new knowledge. This tacit dimension is ignored by Taylor's scientific management. Herbert Simon developed a view of Organisation as an "information-processing machine." He built a scientific theory of problem solving and decision making based on the assumption that human cognitive capacity is inherently limited. He argued that effective information processing is possible only when complex problems are simplified and only when organisational structures are specialised. This http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 22 Cartesian-like rationalist view led him to neglect the human potential for creating knowledge. He did not see human beings as those who actively discover problems and create knowledge to solve them. The Japanese emphasis on the cognitive dimension of knowledge gives rise to a wholly different view of the Organisation - not as a machine for information processing but as a "living organism". Within this context, sharing an understanding of what the company stands for, where it is going, what kind of a world it wants to live in, and how make that world a reality, becomes much more crucial than processing objective information. Highly subjective, personal and emotional dimensions of knowledge have virtually no chance for survival within a machine, but have ample opportunity to grow within a living organism. Once the importance of tacit knowledge is realised, one begins to think about innovation in a wholly new way. It is not just about putting together diverse bits of data information. The personal commitment of the employees and their identifying with the company and its mission become crucial. Unlike information, knowledge is about commitment and beliefs; it is a function of a particular stance, perspective or intention. In this respect, it is as much about ideals as it is about ideas; and that fact fuels innovation. Similarly, unlike information, knowledge is about action; it is always knowledge "to some end." The unique information an individual possesses must be acted upon for new knowledge to be created. This voluntary action also fuels innovation. Although we have made a clear distinction bet explicit and tacit knowledge, they are not totally separate. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 23 They are mutually complementary. They interact with each other in the creative activities of human beings. Nonaka and Takeuchi's theory of knowledge creation is anchored to a critical assumption that human knowledge is created and expanded through social interaction between tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. This interaction gives rise to four modes of "knowledge conversion": (1) from tacit to tacit, which is called socialisation, (2) from tacit to explicit, or externalisation, (3) from explicit to explicit, or combination, and (4) from explicit to tacit, or internalisation. Knowledge conversion is a "social" process between individuals as well as between individuals and an Organisation. But in a strict sense, knowledge is created only by individuals. An Organisation cannot create knowledge by itself. What the Organisation can do is to support creative individuals or provide the contexts for them to create knowledge. Organisational knowledge creation, therefore, should be understood as a process that "organisationally" amplifies the knowledge created by individuals and crystallises it as part of the knowledge network of the Organisation. The infatuation in the West with knowledge management reflects the bias towards explicit knowledge, which is the easier of the two kinds of knowledge to measure, control and process. Explicit knowledge can be much more easily put into a computer, stored into a database, and transmitted online than the highly subjective, personal and cognitive tacit knowledge. Knowledge management deals primarily with existing http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 24 knowledge. But in order to create new knowledge, we need the two kinds of knowledge to interact with each other through the actions of individuals within the Organisation. MIDDLE MANAGERS AS THE KEY PLAYER In Japan, creating new knowledge is not the responsibility of the selected few but that of everyone in the Organisation. No one department or group of experts has the exclusive responsibility for creating new knowledge. Front-line employees, middle managers and top management all play a part. But this is not to say that there is no differentiation in the roles that these three play. In fact, the creation of new knowledge is the product of dynamic interaction among the three kinds of players. Front-line employees are immersed in the day-to-day details of particular technologies, products or markets. While these employees have an abundance of highly practical information, they often find it difficult to turn that information into useful knowledge. For one thing, signals from the marketplace can be vague and ambiguous. For another, these front-line employees can become so caught up in their own narrow perspective that they lose sight of the broader context. Moreover, even when they do develop meaningful ideas and insights, it can still be difficult to communicate the importance of that information to others. People don't just receive new knowledge passively; they interpret it actively to fit their own situation and perspectives. Thus, what makes se rise in one context can change or even lose its meaning when communicated to people in a different context. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 25 Top management provides a sense of direction on where the company should be headed. It does so, first of all, by articulating a "grand theory" on what the company "ought to be". In highly universal and abstract terms, the grand theory set forth by top management helps to link seemingly disparate activities or businesses into a coherent whole. Second, top management provides direction by establishing a knowledge vision in the form of a corporate vision or policy statement. Its aspirations and ideals determine the quality of knowledge the company creates. Third, top management provides direction by setting the standards for justifying the value of the knowledge that is being created. It needs to decide strategically which efforts to support and develop. Middle managers serve as a bridge between the visionary "ideals" of the top and the often chaotic "reality" of those on the front line of business. Middle managers mediate between the "what ought to be" mindset of the top and the "what is" mindset of the front-line employees by creating middle-level business and product concepts. In other words, if top management's role is to create a grand theory, middle managers create more concrete concepts that front-line employees can understand. The mid-range theory created by middle managers can then be tested empirically within the company with the help of front-line employees. Middle managers, who often serve as team leaders of the product development team in Japan, are in a key position to remake reality according to the company's vision. In remaking reality, they take the lead in http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 26 converting knowledge. Although they facilitate all four modes of knowledge conversion, middle mangers make their most significant mark in converting tacit images and perspectives into explicit concepts. They synthesise the tacit knowledge of both frontline employees and top management, make it explicit, and incorporate it into new technologies, products or systems. In this sense, middle managers are the true knowledge engineers of what Nonaka and Takeuchi call "the knowledge-creating company". Middle managers are the key to continuous innovation in Japan. They are at the very centre of a continuous iterative process involving both the top and the frontline (i.e., bottom) employees called middle-up-down. In the West, however, the very term "middle manager" has become a term of contempt, synonymous with "backwardness", "stagnation" or "resistance to change." Some have argued that middle managers are "a dying breed" or "all unnecessary evil". Another impression we have is that the responsibility for knowledge management initiatives in the West rests with the selected few, not with everyone in the Organisation. Knowledge is managed by a few key players in staff positions, including information processing, internal consultancy or human resources management. In contrast in Japan, knowledge is created by the interaction of frontline employees, middle managers and top management, with middle managers in line positions playing the key synthesising role. With a few exceptions, notably GE and Hewlett-Packard, frontline employees are not an integral part of knowledge management. This situation is similar to the days of Frederick Taylor, which did not tap the experiences and judgments of front-line workers as a source of knowledge. Consequently, the creation of http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 27 new work methods for scientific management became the responsibility of the selected few in managerial positions. These "elites" were charged with the chore of classifying, tabulating and reducing the knowledge into rules and formulae and applying them to daily work. The danger of knowledge management is in having the responsibility for capturing the knowledge gained by individuals and spreading it to others in the Organisation rest in the hands of the selected few. Footnotes Thomas A. Stewart, Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations. New York: Doubleday, 1997, p 63. Based on an interview at Stanford, California on 17 June 1997. Peter F. Drucker, Post-Capitalist Society. New York: Harper Business, 1993 p 193. Ibid., p 8. Based on an interview with Dan Holtshouse, who heads the Knowledge Work Initiative at Xerox Corporation at Berkeley, California on 19 May 1997 http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 28 Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi, The Knowledge-Creating Company How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of innovation. New York: The Oxford University Press 1995. Debra M. Amidon, Innovation Strategy for the Knowledge Economy: Tile Kei7 Awakening. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 199 7, p 4 1. The Economist, 'Mr. Knowledge', 31 May 1997, p 7 1. Thomas A. Stewart, op cit , pp 112-113 Dan Holtshouse, 'The Knowledge Horizon', unpublished paper, May 1997. Business Week, 'Management Theory - or Fad of the Motit/7?' June 23 1997, p 37. For his most recent book, see Karl-Erik Sveiby, The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge-based Assets. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1997. See Leif Edvinsson and Michael S. Malone, Intellectual Capital: Realizing Your Company's True Value by Finding Its Hidden Brainpower. New York: Harper Business, 1997, pp 10-15. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 29 See Thomas A. Stewart, op. cit., pp 124-127. Ibid., p 126. For more on Work-Out, see Noel Tichy and Stratford Sherman, Control Your Destiny or Someone Else Will. New York: Currency Doubleday, 1993. See Thomas A. Stewart, op. cit., pp 137-138. The Economist, op. cit., p 71. This section of the paper is taken largely from Nonaka and Takeuchi, op. cit. As we will see later, conversions from explicit to tacit, explicit to explicit, and tacit to tacit are also possible. However, the biggest "bang" in organisational knowledge creation comes from converting tacit to explicit. This section of the paper is taken largely from Nonaka and Takeuchi. Takeuchi, op. cit. Ibid. Ibid. http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm. 30 W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, 'Fair Process: Managing in the Knowledge Economy', Harvard Business Review. Jul.-Aug. 1997, p 71. Based on a personal interview with him in Tokyo on 24 June 1997. Knowledge is defined as "justified, true belief," a concept first introduced by Plato http://www.sveiby.com.au/lessonsJapan.htm.