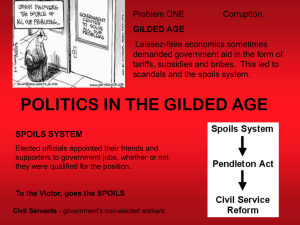

Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act (1882)

advertisement

Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act (1883) The spoils system of political appointments, in which a presidential administration gave out positions within the civil service to individuals who had helped the president’s party, first became a national phenomenon under Andrew Jackson. While Jackson did not create the spoils system, it expanded significantly under his watch. While this system promoted greater participation in politics by providing incentives for helping in party activities, it also placed numerous incompetent and corrupt individuals in positions of power. A new administration would remove nearly the entire civil service positions and assign its political allies to these jobs, making a career in the civil service almost impossible to maintain. In addition, much of the President’s time was consumed with filling hundreds of civil service posts. Calls for civil service reform persisted throughout the nineteenth century, but gained momentum in the 1870s when progressives in the Republican party successfully pushed the issue. The assassination of President James A. Garfield in 1881 by the deranged, “disappointed office seeker” Charles Giteau gave reformers an opportunity to place the blame for the president’s murder on the civil service system. After the Democratic victory in the election of 1882, President Chester A. Arthur lent his support to reform, hoping that passage of civil service legislation would secure Republican appointments in case of a Democratic victory in the 1884 presidential election. Reform came with the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883, written by Dorman B. Eaton, the Secretary of the National Civil Service Reform League. Senator George H. Pendleton sponsored the bill, which set up a three person, bipartisan Civil Service Commission and established the rules for a merit-based civil service system under which posts would be filled through competitive examinations. The Pendleton Act was designed to “neutralize” the civil service by removing any partisan influence from federal appointments. It was not initially successful in this regard, however, because the Act only affected low-level positions – bringing a mere ten percent of the civil service under the new regulations. But the Pendleton Act gave the president the authority to expand the number of positions filled on the basis of merit, which President Cleveland did by bringing 40% of the civil service under the purview of the law. In the years following the Pendleton Act, the civil service would become more efficient and less corrupt, attracting more professional employees and making the government bureaucracy more effective. At the same time, the Act changed the daily activities of the president by relieving him of the burden of filling hundreds of jobs in the federal bureaucracy. Sources: Justus D. Doenecke, The Presidencies of James A. Garfield & Chester A. Arthur (Lawrence: The Regents Press of Kansas, 1981) Herbert Kaufman, “The Growth of the Federal Personnel System,” The Federal Government Service, Ed. Wallace S. Sayre (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1965) Sean Dennis Cashman, America in the Gilded Age (New York: New York University Press, 1993) Richard E. Welch, Jr., The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1988) Paul P. Van Ripper, "Civil Service," Dictionary of American History, vol. II ed. Harold W. Chase, Thomas C. Cochran et. al. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1976)