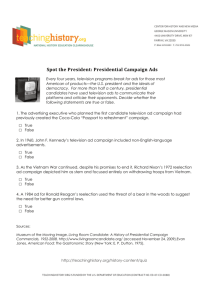

Political Advertising

advertisement

Political Advertising http://Livingroomcandidate.movingimage.us To win an election a candidate must do two things: Develop a message that resonates with voters; and deliver that message. Today, using sophisticated polling and focus group testing, politicians can carefully shape the messages they put out to voters to maximize public acceptance. And detailed knowledge of when certain kinds of voters will be watching TV lets the politician target particular constituents. I. ID Spots Who is this candidate? Images: Athlete, astronaut, Cowboy, businessman, soldier, family man II. Argument Spots Setting up the problems/issues: Non Specific (the problems in DC; New Ideas, Family Values) Emotive Issue (anger) Points Endorsements/Humor/Symbols III. Attack FlipFlop How’s that again General? IV. “I see an America….” Just folks Symbols: Plains, Mountains, Oceans, Mt. Rushmore, Parades, picnics, flags, monuments Consultants In 1952, Rosser Reeves did not commission any special poll to create "Eisenhower Answers America." He simply asked pollster George Gallup for Americans' chief concern. Gallup responded that Washington corruption, the cost of living, and the conflict in Korea topped the list, and Reeves went about shaping ads on those themes. While today, thirty second ads for candidates are taken as a given, in 1952 the Eisenhower campaign needed convincing to use television advertising. Reeves had a colleague prepare a report spelling out the advantages. In the early days of television, companies who wanted to advertise often paid for an entire program. That show would carry the company's name and would only carry the company's ads. Shows like "Camel News Caravan" and "Texaco Star Theater" are famous examples. But Rosser Reeves figured out that if you place your ads between programs you reach the audience built by popular shows at a fraction of the cost. These short advertisements came to be known as "spots" and to be effective had to be brief and memorable. Reeves was a master of the form. Up to this point, most campaigning on television was limited to buying airtime to broadcast speeches. In fact, Democratic opponent Adlai Stevenson's television spending was already committed to speeches. Reeves had spoken to people who'd listened to Eisenhower's speeches and found they retained little of what he'd said. The research report argued that spot advertising should be adapted to the Eisenhower campaign and called for an intensive airing of the spots in the three weeks prior to the election. Script While a few political ads adopt a documentary approach, most start with a script. The script is the initial effort to distill political concepts into an understandable, even dramatic, presentation. Rosser Reeves, through his work on spot advertising, was well prepared for this distillation process. His secret was strict adherence to what he called the "Unique Selling Proposition." USP, as it was called, was a single quality of a product that let it stand out against competition. M&M's were unlike all those messy candies that would melt in your hands, for example. Through repetition, the particular identified quality would stay in consumers' heads when it was time to buy. Reeves took this singlemindedness to the Eisenhower campaign. While he would have preferred just one theme to build the ads around, Reeves took the three concerns identified by Gallup (Korea, corruption, and cost of living) and wrote a series of scripts. None of the short spots would deal with more than one topic, each of them consisting of a single question asked of Eisenhower by a "typical" voter. The candidate's responses were culled carefully by Reeve's reading Eisenhower's many campaign speeches. So, in essence, the message of the candidate matches the rest of the campaign, but the spot presents that message in a simplified, memorable form. Shooting Shooting a political ad starts the transformation of ideas into images. To keep viewers engaged, television advertising needs to communicate visually. Slogans and scripted words work only on one level of perception. Think of how often you see a flag in political ads. Here the candidate wants to build associations between him or herself and the patriotic feelings brought on by waving the flag. But this is only the most obvious example. For "Eisenhower Answers America," Rosser Reeves filmed Eisenhower in an empty studio. Visually there is very little to distract viewers, no flags or symbols of power. But Eisenhower is filmed from a slightly low angle, meaning we look up at him. The voters asking questions are filmed looking up as though addressing someone of enormous stature. Eisenhower is always seen alone, he doesn't share the frame with his questioners. In fact, the questioners never actually spoke with Ike, they were filmed later. Reeves recruited tourists at Radio City Music Hall and had them ask scripted questions in the studio a few days after Eisenhower was filmed. While some Republican leaders worried that appearing in a commercial would diminish Eisenhower's stature, in the ad his stature is visually enhanced. At the same time the candidate is seen relating to everyday people, and offering memorable solutions to their problems. At times, however, Eisenhower seems a little wide-eyed and unfocused, probably because Reeves didn't want him to wear his glasses and he is struggling to make out large cue cards. Ike is said to have moaned, "To think an old soldier should come to this..." How Effective? No clear definition of how effective. Perhaps most effective in raising overall discussion. Good ads get news/opinion people talking. Free Replay I. Testing Testing Testing Many ads shelved because focus groups misunderstood/didn’t understand/didn’t like the ad. Negative Ads NEVER test well II. ID ads work well to get candidate known/raise money/raise positives III. Negative ads Risky Memorable Hardens positions Must be seen as Fair More dangerous of incumbent Sometimes meant to provoke (Kerry vote for/against) IV. Can polish a candidate’s image Framing/priming The man from Hope V. Advertising can’t raise the dead or substitute for actual campaign 195In 1952, Rosser The Paradox Reform Depends on Voter Savvy of Political Ads By Kathleen Jamieson In 1988 I studied the information absorbed by 100 people during a season of presidential campaign news and advertising. I conducted focus groups, talked to individuals about their recollections of the campaign and observed their reactions throughout. About halfway through the process I realized that what these typical voters were learning from the news and political advertising they saw was everything they needed to know not to be voters, but to be campaign consultants. TV viewers understood, for example, that George Bush's ad about prison furloughs was designed to make Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis look "soft on crime." But they didn't know what either candidate planned to do about crime, homelessness, economic policy, the environment or other major issues of the day. A major crisis such as the savings and loan bailout--one of the most expensive giveaways in U.S. history--was ongoing at the time but never seriously debated. Instead of a discussion of issues, voters were treated to analyses of polls and polling, gaffes and media gurus, media buying requirements and inside information on campaign staffing shake-ups. Still worse, broadcast news and much print journalism focused on the strategic intent of misleading ads but not their accuracy, fairness or relevance to governance. The most analyzed and talked about image of the campaign completely sidestepped the question of what either major candidate would do if elected president. Known as the "furlough ad," it depended on innuendo and visual images to link Michael Dukakis with the supposed dangers of a prison furlough program and therefore with a dangerous breed of liberalism. When the announcer's voice intoned "many first-degree murderers escaped" as the words "268 escaped" appeared on the screen, the human need for closure caused viewers to associate the number 268 with the word "many," encouraging them to assume that many prisoners committed crimes while on furlough. Furloughed prisoner William Horton's name was never mentioned. It didn't have to be. Reporters mentioned it often as did Bush in network soundbites. With those soundbites came Horton's menacing mug shot. Campaign managers could also depend on political reporters to find and publicize the story of the one prisoner who assualted and raped while on furlough. And they could expect audiences to draw desired false inferences from an ad that was not technically incorrect: First-degree murderers did, in fact, escape. Four did. And of those four, only one--Horton--committed a violent crime. In a 10-year period, 268 prisoners escaped, which meant that Massachusetts had the best record of the industrial states. Other facts about the program--its purpose, its duration, the number of prisoners released, the screening process--were also obscured. Most obscure of all was the basic unfairness of judging Michael Dukakis' fitness to be president on the basis of the "facts" presented in this ad. The president, after all, cannot change the furlough programs in the states. And it is the states and localities, not the federal government, that are responsible for crime prevention anyway. This brand of unfair editing can be traced straight back to the '30s, but it gained prominence in a campaign ad from the Kennedy-Nixon race of 1960. In a Kennedy effort, pictures of Nixon nodding his head from the campaign's televised debates were used to make it appear that Nixon agreed with the Kennedy program. But inevitably, suspect claim-making didn't work. In 1964, the Goldwater campaign created its own backlash with a 30-minute campaign film that contrasted such images as cleancut, smiling children saying the pledge of allegiance (representing the Republicans) with scenes of supposed Democratic immorality and decadence. Because the juxtaposition was too obvious, the film became a cause celebre, and the Johnson campaign ended up using it as one of its own campaign documents. Nevertheless, the lesson was learned: Rapid intercutting of visuals can short-circuit the normal logic of viewer's thought processes. Viewers are also slow to recognize that most ads feature actors and are highly sophisticated marketing tools using professional directors and the latest high-tech editing techniques. As viewers, we react mainly to their emotional content. Although viewers are often knowledgeable about why campaign advertising and marketing stress particular themes, this form of media sophistication is very different from the kind of media awareness or media literacy that defuses the impact of emotionally manipulative ads. Partly this gap arises because most criticism of advertising is verbal, while the ads themselves are visual. When the visuals disagree with the narration, people tend to base their assumptions on the visuals. But in correcting ads, reporters focus their attention on what is said, not what is shown. Some other 1988 campaign ads demonstrate this seeming paradox: An anti-Bush Dukakis commercial associated the Republican candidate with cuts in the social security system. As a senator, George Bush did actually vote for a freeze in social security cost of living adjustments (not actual cuts). A visual showing a social security card being torn up associated him with massive cuts. Scenes of a polluted harbor linked Dukakis with Boston harbor problems. Such visuals are absorbed by viewers who can't tell where the pollution shown originated. In fact, the Boston Harbor ad was effective in creating doubts about how the mildly pro-environment Dukakis would stack up against the arguably less environmentally aware record of his opponent. Which brings us to the question: How effective is political advertising? Studies of political ads show that they can make a difference in close elections. But their influence is complex and can operate in peculiar ways. One often-ignored factor is political advertising's importance as a source of political information. For people who don't seek out other forms of political information--the very voters whose response to ads is greatest--the effect of political advertising is magnified. It may be even more important in state and local races where other forms of political information are less available. Almost no piece of communication has what is called a "direct effect," a measurable change in behavior based on one exposure. But the effectiveness of political advertising is based not on one viewing but on many. Much research has shown that repetition can predispose a viewer or listener toward an ad's assumptions. In 1988, one out of four voters told pollsters that their voting decisions had been influenced by advertising. When you combine these reactions with many voters' lack of exposure to other political information and the manipulative nature of many ads, the consequences are disturbing. If we take it as a given--as I do--that an electorate possessing accurate information about the things its members value is necessary for democratic functioning, we have to be concerned when political advertising is misleading and when it drives out other forms of communication. What's the remedy? A number of other democracies restrict the campaign process in various ways to minimize the impact of manipulative ads or promote substantive debate on the issues. But such regulations would represent a revolution in our free speech traditions and the system of commercial access for political ads. Advertising-savvy journalists can help by following a "news grammar" that avoids media manipulation by campaign managers. Correcting the claims of unfair ads, and hard questions about advertising's relevance to how candidates propose to govern, can help. But some ads are so insidious that their impact defies journalistic caution. Ultimately the true remedy must come from the voters themselves. TV viewers need to take a hard look at political advertising, the ordinary as well as the blatant. If campaign managers recognize that substance is what sells, they will be forced to provide it. Voters must demand that candidates answer real questions about themselves and their lives. Only then will they cease to be political campaign managers and become instead informed determiners of their country's future. Author: Kathleen Jamieson is dean of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania/Philadelphia. She is a widely recognized authority on political advertising and the author of several books on political ads and their effects.Reeves did not commission any special poll to create "